For various, much-cited reasons to do with what was going on in the wider world, 2023 wasn’t a great year for the international art market. But 2024 promises to be better. At least, that’s what some experts are predicting—or hoping.

According to the 2023 A Year in Review report by the London-based art market analytics firm ArtTactic, auction sales of Old Master, Impressionist, Modern and contemporary works at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips—the key publicly available indicators of health (or otherwise) in this particular industry—dropped 27% last year, to $5.76bn. The firm “largely” attributed this result to “a 30% fall in the number of $10m-plus lots entering the market in 2023”.

Will the supply of trophy lots improve in 2024? “There are a number of exciting collections that will be unlocked,” said Bonnie Brennan, Christie’s president of the Americas, during the company’s annual conference call with journalists last December. It only takes the sale of a few major single-owner troves to create perceptions of a boom, regardless of what might be happening—or not—elsewhere in the trade.

Horrific wars are grinding on in the Middle East and Ukraine, but with the S&P 500 index of US equities up 24.7%, the Nasdaq Composite index of tech stocks up 44.5% and Bitcoin up by more than 150% by the end of 2023, plus the US Federal Reserve and other central banks predicted to reduce interest rates in 2024, the financial backdrop would now seem to be more conducive to rich collectors getting richer, and perhaps buying and selling more big-ticket art.

But interestingly, there are also predictions of resurgence further down the price chain. ArtTactic’s report states that the lower end of the market remained “very active, with an 18% increase in the number of artworks sold below $50,000” last year.

In December, the influential New York art adviser Josh Baer pronounced in his trade insiders’ newsletter, The Baer Faxt: “Everyone has acknowledged an art market correction, but let us be the first to predict an upcoming bull market.”

Baer expects this new surge of sales “will be more in terms of volume rather than price”, boosted by generational shifts in capital, growing wealth inequality, a comeback for NFTs, lowered interest rates and a lot more cash and buyers entering the market. “The collector pool is still in the mid tens of thousands, but imagine, say, 200,000 to 300,000 collectors,” Baer adds.

‘Conversion problem’

Art world professionals have long hoped for a game-changing expansion of a market whose overall sales have stubbornly fluctuated between $57bn and $68bn since 2010, according to the estimates of the annual Art Basel & UBS Art Market report.

For the New York-based art economist, entrepreneur and author Magnus Resch, whose latest book, How To Collect Art, has just been published, the art trade has a serious “conversion problem”. Plenty of people look at art, but few actually buy.

“The art world is still a mystery to many. They don’t find answers to the three most important questions: What should I buy? Is the price fair? Is it a good investment?” says Resch.

“People go to an art fair, and they’re overwhelmed. About 80,000 go to Art Basel Miami Beach, and maybe 2,000 of them buy something. That leaves 78,000, of which maybe 20,000 have the financial means to buy at the fair,” he adds.

Resch estimates the market’s pool of “important” collectors, who spend more than $100,000 on art annually, at only about 6,000 individuals. Last year, the UBS Global Wealth Report estimated the global population of millionaires at 59.4 million.

Given the seeming colossal shortfall between those who can afford art and those who actually buy it, how can the market expand?

“Education plays a key role,” says Resch. “Dealers should show prices, and there needs to be an honest conversation about the market. People need to be aware that 99.9% of art isn’t a good investment. The art trade needs to be less VIP and more inclusive,” he adds.

Herein lies the central paradox of today’s art market. Resch’s refreshingly honest insider’s guide to collecting is filled with the author’s and fellow experts’ exhortations for newcomers to buy what they like and not worry about making a profit.

But How To Collect Art also looks like a business manual: there are no illustrations, and there is no discussion of the aesthetic value of any work. Although there are no “definitive criteria” to clarify what good art is, Resch writes, art is “susceptible to economic analysis as much as any other product”, meaning collectors, like home stock traders, should rely on data to identify which artists might be a good investment.

So collecting art becomes a names and numbers game that, apparently, is very difficult to win. Which is probably why 78,000 people turn up to an art fair to window shop, rather than actually shop, and one key reason why the market fails to meaningfully expand.

A new Gilded Age?

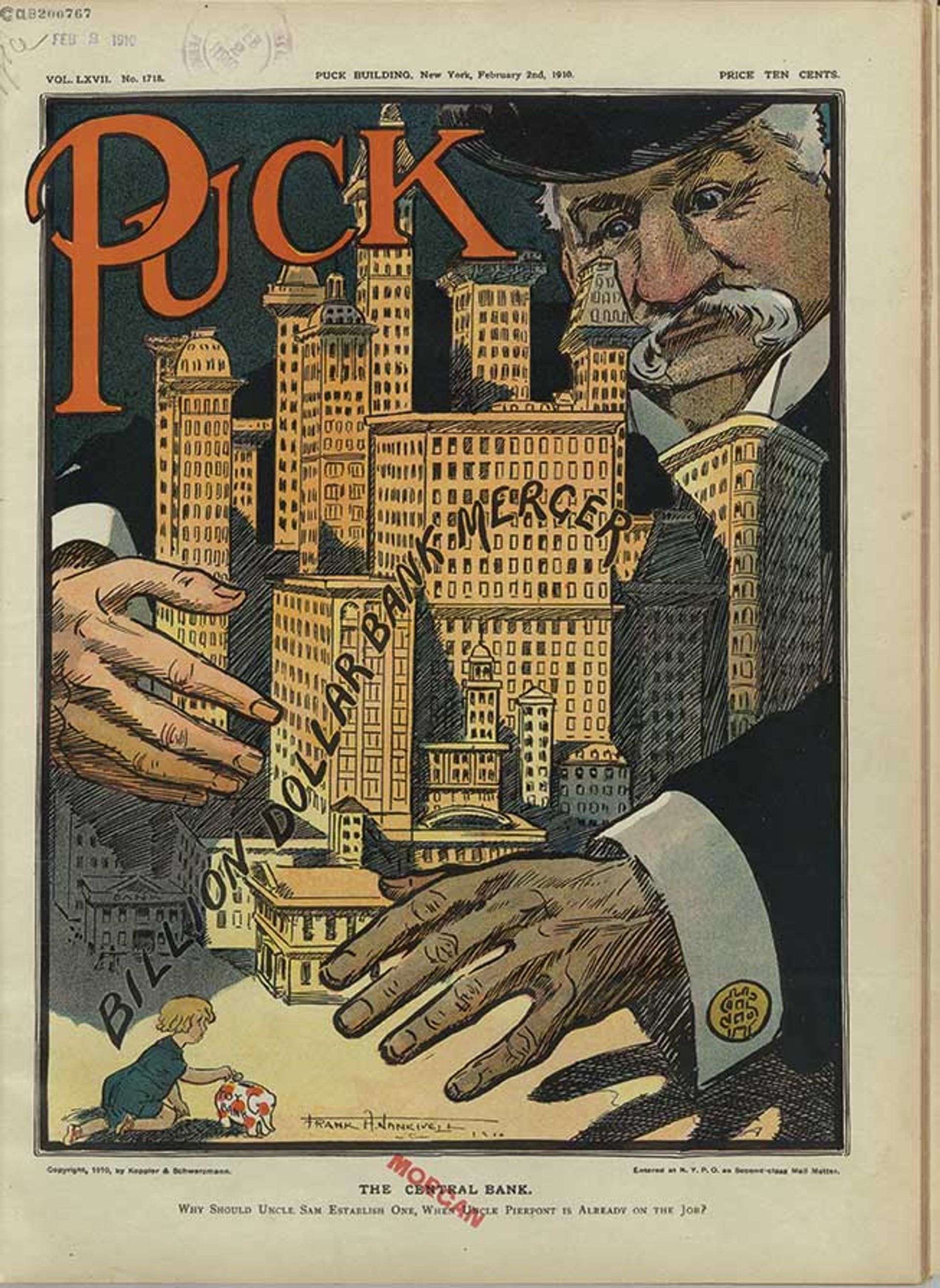

Today’s levels of wealth inequality—generally a boon for top-end art prices—have prompted comparisons with the age of the Robber Barons. In 1890, 11 million of the US’s 12 million families lived below the poverty line, while magnate collectors like Henry Clay Frick, Henry Huntington and John Pierpont Morgan spent fortunes on paintings by famous European masters that enhanced what the sociologist Thorstein Veblen, in his 1899 study The Theory of the Leisure Class, identified as their sense of “reputability”.

But as Douglas Rushkoff, the author of Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires, pointed out in The Guardian, today’s digital Robber Barons, unlike their Gilded Age forebears, “don’t hope to build the biggest house in town” but rather the biggest “colony on the moon, underground lair in New Zealand or virtual reality server in the cloud”. This makes collecting art, let alone building museums, generally surplus to the reputations of the new breed of ultra-confident, ultra-rich entrepreneurs.

Yet the Great Wealth Transfer, the process by which an estimated $15 trillion or more of assets will pass down the generations by 2030, is still regarded by many in the art trade as a serious dial-mover.

Certainly the dynamics of tax-optimised inheritance have recently been responsible for some spectacular single-owner auctions, such as the $1.6bn Paul Allen sale at Christie’s in New York in 2022 and the $425m Emily Fisher-Landau sale at Sotheby’s in New York last November. Further high-value “boomer” generation collections may well bump up the market’s headline numbers this year, as Brennan of Christie’s expects.

For Robber Barons last century, fine art was a status symbol. But today’s tech billionaires may not have the same view

US Library of Congress

And then there is that potential new wave of younger buyers who have either inherited considerable wealth or made money for themselves. Christie’s statement on its end-of-year results highlights a “65% rise in new Gen Z buyers (driven by handbags, watches and prints)” and Millennials making up 34% of all new buyers.

“The top end of the art market will see a gradual shift and a new generation should step in. But it will be interesting to see to what extent this younger generation shares the same interests as the old guard,” says Anders Petterson, the founder and chief executive of ArtTactic.

ArtTactic’s research does show that auction sales of prints and limited editions—a sector favoured by younger art buyers—generated $103.2m last year across Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips, an increase of 18.3% on 2022. “Instantly recognisable images by established names can be bought at affordable price points,” says Petterson, who nonetheless concedes that these days even a $20,000 Damien Hirst print has become unaffordable to the professional class of collectors who used to underpin the art market.

“The disposable income of the middle classes has been squeezed,” Petterson says. “They don’t have the same amount of funds for recreational, non-essential spending.”

Back in the days of those Robber Barons it was not just the super-rich whose walls were crammed with art. Thousands of middle-class homes in thousands of cities and towns across North America and Europe were routinely decorated with collections of original pictures or limited-edition prints.

The habit of living with art has fallen out of fashion across almost all income levels. If 300,000 new buyers are going to enter the market, a lot more people with plenty of disposable income will have to start collecting and stop worrying about possible financial returns. But in an age when education, a career, housing, childcare, healthcare and pretty well every aspect of life in a neoliberal economy is required to be a sensible investment, can that particular genie ever be stuck back in its bottle?