Some call it the great exodus: the family company owners, the bankers and the expatriate businesspeople departing Hong Kong in droves during and since the Covid-19 years. But departing cultural workers have been more motivated by mainland China’s growing controls over free expression and education than by lifestyle inconvenience. The numbers of Hong Kong departees are climbing in the hundreds of thousands by most estimates. But more numerous, if quieter, are those remaining, at least for now, out of a steely determination to bear witness and push back.

“I decided to stay because HK is my home!” says Mak2, the public name of the artist Mak Ying Tung. “I believe in the power of art to inspire change and I feel a deep-rooted connection to the local culture. The mood among us is mixed: there’s a sense of uncertainty, but also an undercurrent of resilience.”

“It is essential for progressive people to stay in Hong Kong,” says John Batten, a critic and photographer who also calls Hong Kong his home, and has for decades been a familiar fixture of the city’s art scene. “You hear, particularly during the 2019 protests, that ‘Hong Kong is hopeless; no future...’ This can easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The Hong Kong diaspora has always been fluid, people come and go, and this would apply to artistsJohn Batten, Hong Kong-based critic and photographer

Mak2 Image: © the artist

Permanence of departures ‘pure conjecture’

The extent of the art world exodus “is just anecdotal”, Batten says. While many have indeed left, the permanence of their departure is “pure conjecture”, he says. “What is more accurate is that only one, Kacey Wong, who is very explicit in his denunciation of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on social media, would possibly be detained under the National Security Law if he were to return to Hong Kong. The Hong Kong diaspora has always been fluid, people come and go, and this would apply to artists. I think we need to wait longer to see who stays away.” Another artist who has been open about moving is the prominent cartoonist Justin Wong—“but rarely do artists make big announcements about leaving”, Batten says.

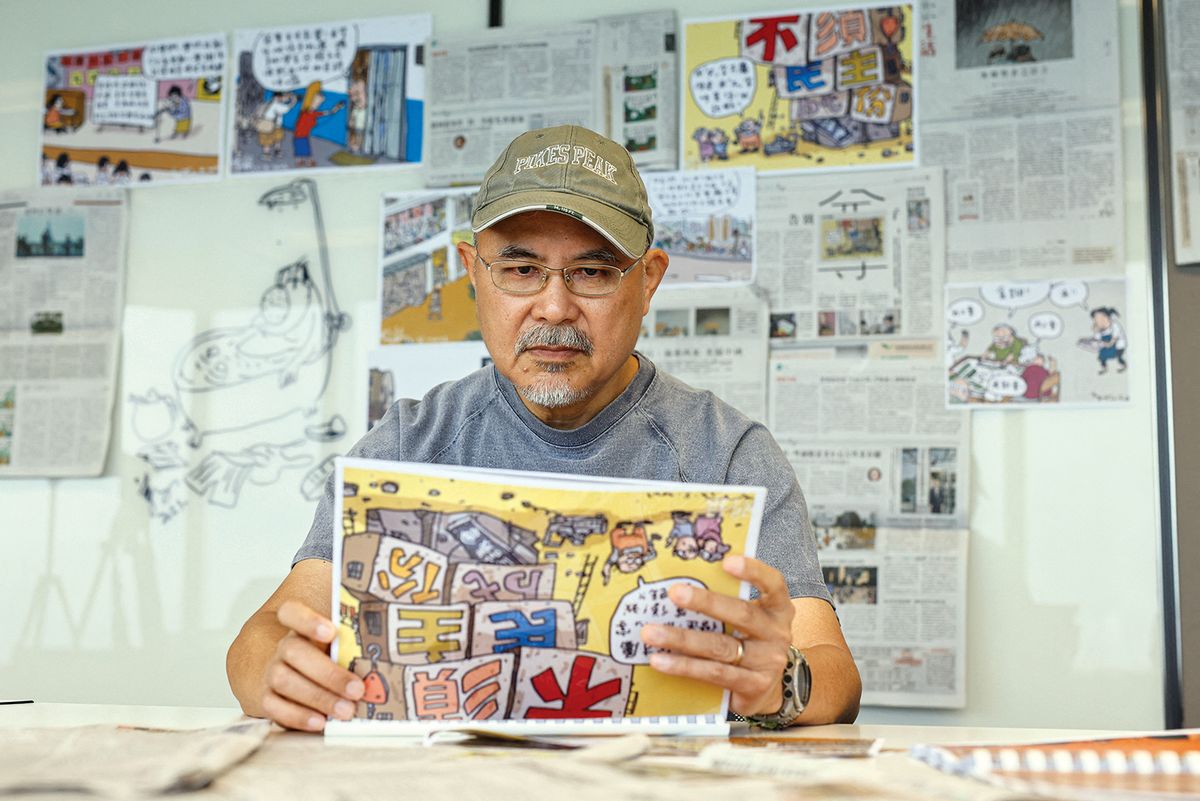

To date, government-led crackdowns on critical speech have largely targeted demonstrators and the media, as evidenced by the ongoing trial of Jimmy Lai, founder of Apple Daily newspaper. Batten says the originally independent but government-funded broadcaster Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) has clipped away critical content and that “the great freedom of press that Hong Kong had for so long has been truncated”. But the internet remains open without any of the Great Firewall censorship of the mainland. The satirical cartoonist Zunzi has stopped publishing after pressure was put on the Ming Pao newspaper, but he continues to live in Hong Kong.

Since 2020, however, the “winds of intimidation” hang heavy over all arts entities, Batten says, leaving many concerned about violating the National Security Law (NSL), which was introduced on the eve of the 23rd anniversary of the city’s handover to China from British rule in 1997. The law criminalises acts of secession, subversion of the state, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces. It was drafted by Beijing, bypassing Hong Kong’s legislature.

The police has been “quite light-touched” in its interference in exhibitions, according to Batten, with no changes demanded so far. But self-censorship in the press and within arts organisations is “real and happening”, he says.

The city’s high cost of living and cramped working spaces are a perennial challenge too. “For artists in Hong Kong, one of the biggest hurdles in making a name for themselves is the [expense], especially the rent,” Mak2 says. “This financial strain is particularly tough on young, emerging artists who are just starting out. They often struggle to find affordable studio space and cover the costs of materials and living expenses.”

Artists also feel pressure to leave for professional opportunity, to escape the glass ceiling that remains for Hong Kong-based artists. While Western galleries eagerly sign mainland Chinese artists, few—even those with Hong Kong locations—represent home-grown artists.

“Hong Kong is a small city and this engenders a smaller art market; these two components are symbiotic and reciprocal,” says Mimi Chun, the director of the Hong Kong gallery Blindspot. “Hong Kong is known for its score of major international galleries. Sadly, they have a tendency to only represent blue-chip artists.” Other local galleries including Empty, Kiang Malingue, Ora-Ora and de Sarthe focus heavily on Hong Kong artists.

In Hong Kong, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought the art community closer together, fostering a new-found sense of belonging among a younger generation of local artistsPascal de Sarthe, gallerist

Artists who have recently left Hong Kong generally remain closely connected to the city and its cultural milieu. “On a positive note, in Hong Kong, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought the art community closer together, fostering a new-found sense of belonging among a younger generation of local artists,” says de Sarthe gallery’s founder, Pascal de Sarthe. “Artists, writers, and gallerists began engaging in open and meaningful conversations about art, creating a dialogue that was previously absent. Hong Kong artists now aspire to establish a presence on the global art platform.”

“Hong Kong with its seven million people has always punched above its weight,” Batten says. “But, we are also constrained, realistically, by our size. We should aim for excellence in some art areas, not spread ourselves thinly by trying to be the next big thing in all areas of art, technology and business.”