There are paintings by Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)—the ne plus ultra of German Romantic artists—that are so celebrated and widely reproduced we can see them with our eyes closed. Known for his enthralling depictions of nature in paintings such as The Sea of Ice (1824), which dramatises a forbidding Arctic shipwreck, Friedrich seems to allow the viewer to experience the sublime—not by journeying to the Arctic, or climbing a mountain, but by looking at a work of art.

The challenge of staging a Friedrich show is that he almost certainly had something else in mind. A careful and expert draughtsman, whose works are controlled compositions, he devoted his career to creating art that is arguably less about nature’s wonders, let alone its sublime terrors, than about its pliability. His synthetic landscapes—and he is, to a remarkable degree, exclusively a landscape artist who almost entirely avoided depicting the human face—are not really natural at all. They are typically manipulations, creations, no less shaped and refined than a Johannes Vermeer interior.

In The Sea of Ice (1824) Friedrich seems to allow the viewer to experience the sublime Photo: Elke Walford; © Hamburger Kunsthalle/BPK

This measured artificiality can be demonstrated only in a substantial survey that assembles signature paintings from several German collections and co-mingles them with fragile works on paper to reveal Friedrich’s underlying methods and overriding concerns. In this 250th anniversary of Friedrich’s birth, the world is being treated to a series of related surveys in three German cities sharing a small group of core paintings. The first, at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, is nothing short of a curatorial triumph.

Featuring around 160 Friedrich works, along with some three dozen by his followers and contemporaries, Caspar David Friedrich: Art for a New Age is installed in the museum’s hushed-cube Galerie der Gegenwart. Hung primarily in several smallish, low-ceilinged spaces—with expanded inner vistas for major works such as Moonrise over the Sea (1822)—the show first develops chronologically then thematically, starting with early and late depictions of the illusive artist himself.

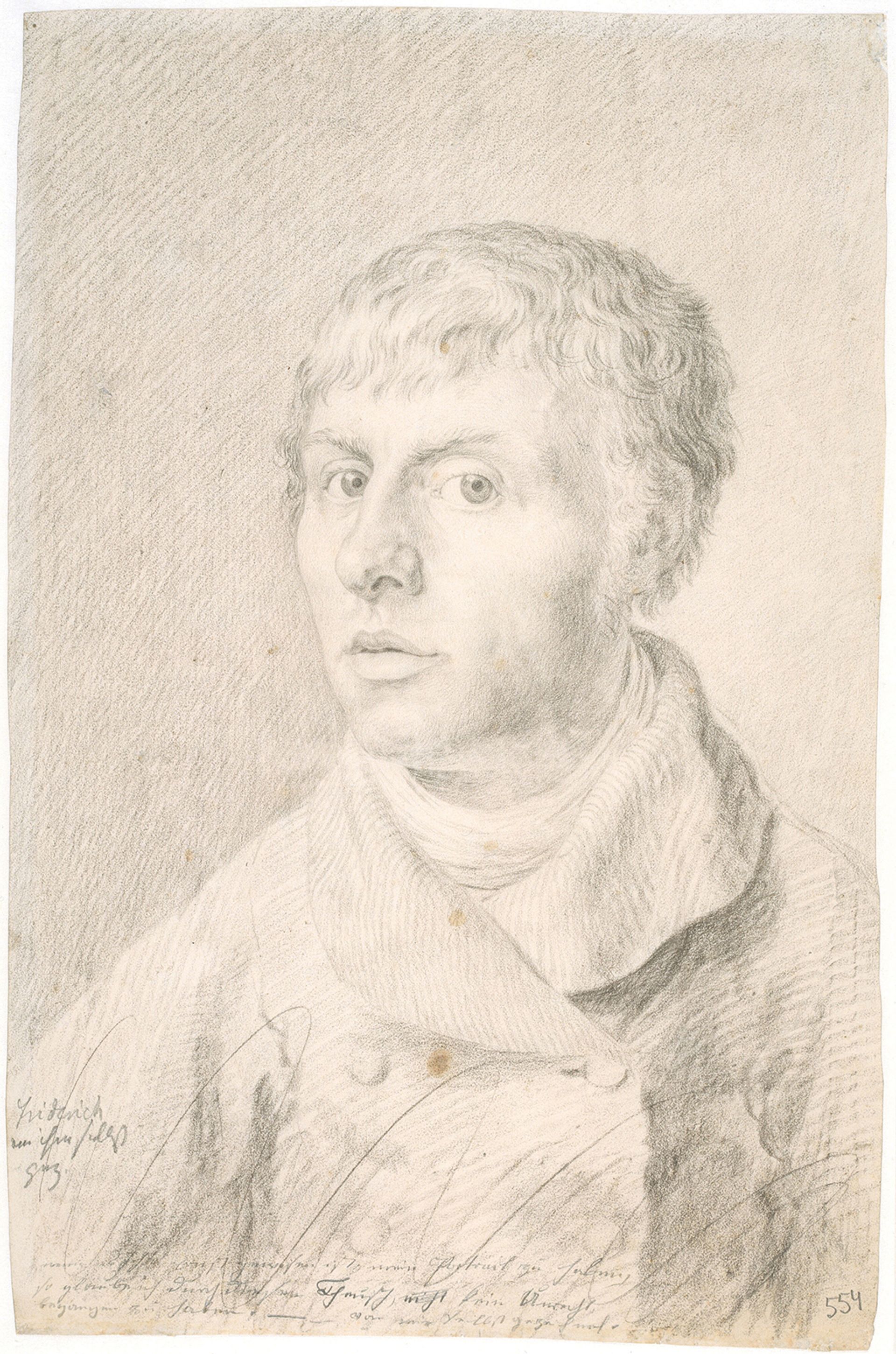

Friedrich was born in what was then a Swedish-controlled outpost of northern Germany. He studied in the 1790s at the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where draughtsmanship was put far ahead of painting. In a stark self-portrait drawing from 1800, he still looks like an art student, catching himself in a fierce, vulnerable pose.

Self-portrait (1800) reflects the artist’s early devotion to draughtsmanship rather than painting Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Having settled for good in Dresden by 1800, Friedrich did not really take up painting until his 30s, and the show is rich in early drawings that reveal the origins of his graphic approach to oil on canvas. A 1799 drawing of rock formations, with a curious cross in the middle, foreshadows his tendency to use topographical elements as raw material. And the rich sepia tones of these early drawings remain a part of his painterly palette—Moonrise over the Sea, which features a darkened shoreline and purple sky, could in part be an illumined drawing.

Figuring out Friedrich’s intentions has been a vocation for a host of critics. Helmut Börsch-Supan, the German art historian who edited Friedrich’s catalogue raisonné, views him as an essentially religious artist, and his landscapes as spiritual allegories, while Joseph Koerner, the American art historian who wrote a still influential 1990 study, sees him as an analytical, if despairing aesthete. Both of these interpretations overlap in a large section devoted to Friedrich’s sculptural use of ecclesiastical elements. In Ruins of Eldena Abbey in the Giant Mountains (1830-34), he transfers the remnants of a north German Cistercian monastery into the kind of high hills not far from Dresden.

Ruins of Eldena Abbey in the Giant Mountains (1830-34) transfers the remnants of a north German Cistercian monastery into the kind of high hills not far from Dresden Stiftung Pommersches Landesmuseum

The Western landscape tradition nearly always uses landscape to contain human endeavours; in Friedrich, the artist-cum-viewer is often the only person involved

The curators place this work in a category they call “landscapes with human traces”—the building fragments being the most prominent sign of life—and it is striking how seldom Friedrich depicts human activity. The Western landscape tradition, from the Dutch Golden Age to the 19th century’s French Barbizon School, nearly always uses landscape to contain human endeavours; in Friedrich, the artist-cum-viewer is often the only person involved. Outdoor oil sketches became popular in Germany in the 1820s, and two of Friedrich’s rare, figure-free attempts have been brought to Hamburg. Evening (1824), an oil-on-hardboard work from Mannheim, is pure colour. We can see here why 20th-century critics would compare Mark Rothko to him.

The curators remind us that when Friedrich does include figures, they often have their backs to us. It is a traditional device in Western art, but one to which he gave a new compositional force to. Long regarded as a stand-in for the artist, the Rückenfigur, as Germans call it, became for Friedrich a way to organise a painting.

In Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (1818) Friedrich positions three separate figures at a celebrated spot on the coast of Germany’s largest island. Often promoted as a Romantic ode to a natural German wonder, the painting is given a more thoughtful context as an allegory about perception. The three figures are contained in an area of sea framed by the cliffs, which in turn are framed by foliage. The show helps us understand that this picture within a picture uses nature to comment on the act of making art; it is the equivalent, in its way, of Vermeer’s The Art of Painting (1666-68).

Friedrich’s interest in emptiness is echoed in the hanging of the show, which makes ample use of empty space. Easter Morning (1828-35), with its own blue-grey wall, is a near-existential late painting. The work’s three Rückenfiguren are framed by a pair of naked tree clusters. There is nothing Romantic about this scene, which urgently reminds us of Edvard Munch.

Incapacitated by a stroke in the mid 1830s, Friedrich was already out of fashion by the time he died in 1840, and on his way to a posthumous oblivion that would end only in the next century when museum directors in Berlin and Hamburg repackaged him as artistic icon of the new German Reich. The show winds down with these late works, including his last major painting, Hamburg’s own sepia-skied Sea Shore in Moonlight (1835-36), and then returns us to the first gallery and the many faces of the artist. We may not fully understand him at this point but we probably know him better than we ever have before.

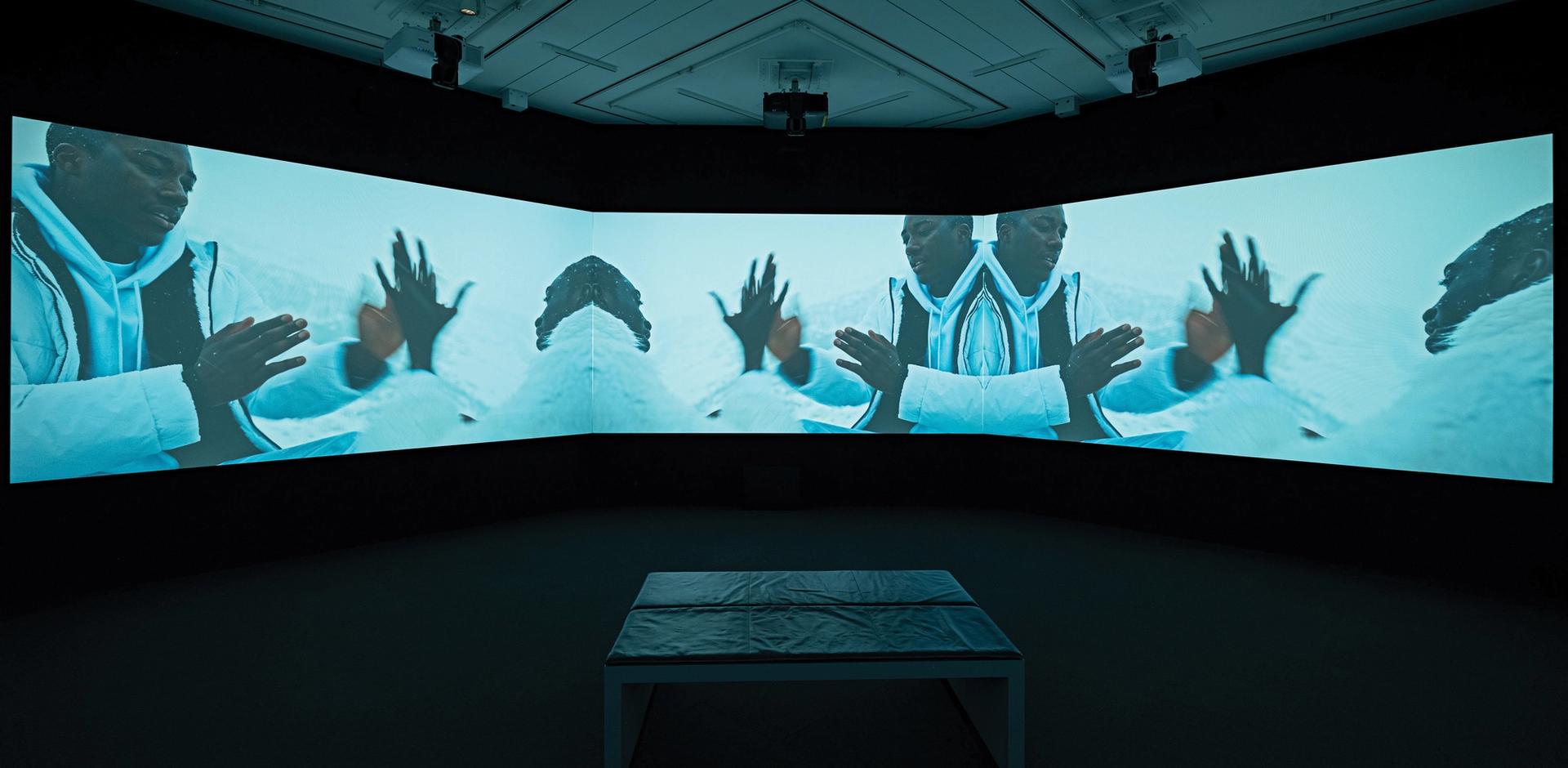

Kehinde Wiley’s six-channel digital film The Prelude (2021) is one of the works by 20 contemporary artists shown alongside Friedrich’s Photo: Fred Dott; courtesy of Rennie Collection, Vancouver

The curators threaten to gild the lily by adding works by some 20 contemporary artists in a continuation of the show on the floor above. Each one presumably has some thematic affinity with Fredrich, and about half are directly commenting on him. I was deeply moved by two works in particular. Wildfire (meditation on fire) (2019-20), a video installation by the Belgian artist David Claerbout, flickers in and out of abstraction, using technology to manipulate beautiful and terrible images of a real fire. And Kehinde Wiley’s The Prelude (2021), a six-channel digital film, takes Black Londoners to a polar-looking Norway, where they are encased in a whiteness that is by turns sinister and beautiful, and ultimately just empty. Like Friedrich, the two artists have created equivocal art that mesmerises.

What the other critics said

In the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Stefan Trinks says: “whenever Friedrich paints or draws nature, he is painting an idea of nature”. He cites The Watzman (1824-25), “a collage of many drawings of very different rock formations, ranging from Silesian to Saxon low mountain ranges, which Friedrich merges into the quintessence of an ideal mountain”. In the Hamburger Abendblatt, Vera Fangler says the show has “left the chronological path in favour of a thematic focus”. She adds: “For, as is so often the case when art unfolds its magic, no amount of explaining helps. ‘See for yourself!’ the curators say to their audience.”

• Caspar David Friedrich: Art for a New Age, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, until 1 April

• Curators: Markus Bertsch and Johannes Grave, with Ruth Stamm