The estate of the American Pop artist James Rosenquist (1933-2017) will offer around 50 of his prints, made across 50 years, for the first time in a Phillips auction in New York on 15 February. It’s no money-spinner—the sale’s total estimate tops at $410,000, with some lots starting at $400. Rather, says Mimi Thompson, the artist’s widow and the board director of his estate, the aim is to “put images in the hands of people who could spend $1,000”.

The strategy isn’t a completely new one for the estate, which has chosen more accessible ways to widen Rosenquist’s appeal in recent years. Notable among these was a 2021 collaboration with the luxury brand Lanvin, something Thompson says coincided with the need to think more creatively during the Covid-19 pandemic.

She concedes that the artist, for whom printmaking was core, is not as famed as his contemporaries Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, partly because his more layered and surreal take on Pop is more complex. But lots of artists get it—David Salle and Jeff Koons cite Rosenquist as an influence, while KAWS (aka Brian Donnelly) is said to own his work.

But Rosenquist’s concerns, even as far back as the 1960s, should chime with a more general audience today, Thompson urges. These include his pre-occupation with the impact of consumerism on the environment as well as his socially conscious and anti-war leanings.

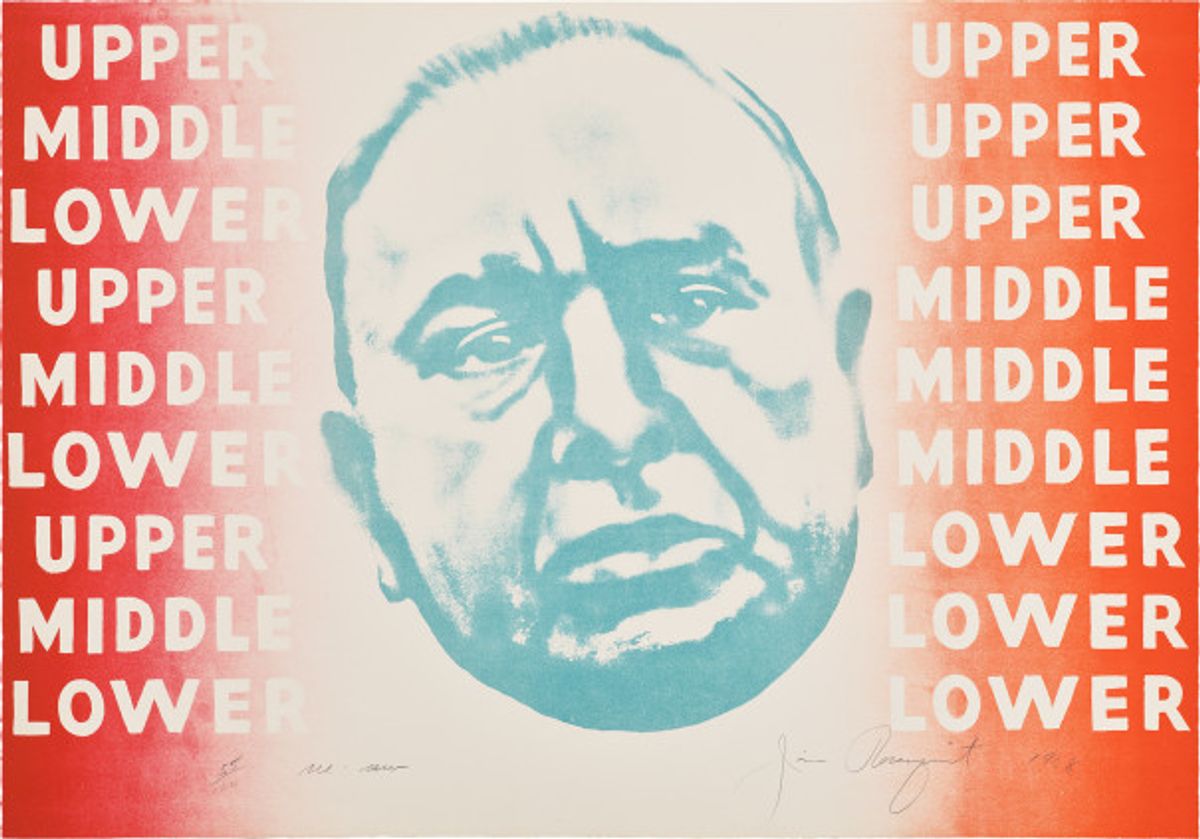

“Election years were always a good opportunity to make a comment,” Thompson says. She highlights Rosenquist’s 1968 lithograph See-Saw, Class Systems (G. 22), estimated at $500 to $700 at Phillips; the work shows a scowling Richard J. Daley, the then-mayor of Chicago, who had denounced the mass demonstrations against the Vietnam War during that year’s Democratic National Convention.

In the first half of this election year, Rosenquist is having his moment across sectors. As well as the Phillips auction, New York’s Museum of Modern Art is showing his 2011-12 painting The Geometry of Fire from 1 February, while his vast, 59-part F-111 (1964-65) remains on view in the museum’s permanent collection galleries.

Such institutional commitment is a mark of the work done by the estate and its galleries, Thaddaeus Ropac and Kasmin, plus Rosenquist’s lifetime champion Castelli. Ropac says he is completely supportive of the Phillips auction—and at the time of writing, he was preparing to feature a $1.5m painting by Rosenquist at Singapore’s Art SG fair—aptly, his Untitled (Singapore) from 1995. Castelli, meanwhile, has a show dedicated to Rosenquist’s monumental 1994 installation The Holy Roman Empire Through Checkpoint Charlie (until 13 April).

Thompson says selling the 50 prints through a gallery was an option, but that the enthusiasm and creativity of the Phillips team, plus the one-night-only impact of an auction, won through. The live sale is accompanied by a catalogue, to which some of Rosenquist’s print collaborators have contributed, and preceded by a two-week exhibition, so the estate gets the best of both worlds. Thompson summarises: “Jim loved to experiment. This will be an adventure, and we are always up for that.”