“He was a real innovator,” says Martin Parr, remembering fellow British photographer and longtime friend, Brian Griffin, who died at home in London last weekend, aged 75. “He really livened up the whole world of portraiture. They [his portraits] were so recognisably his. No one had ever seen anything like them. And not many photographers can say that.”

Griffin is best known for his iconic album covers, such as Depeche Mode’s A Broken Frame (1982) and Joe Jackson’s Look Sharp (1979), but he was much more than a rock photographer, injecting surreal narrative and noir lighting into commercial and editorial commissions, while pursuing his own projects. Griffin made no distinction between personal and assignment work; he put equal energy and ambition into both, always looking to create some playful visual disruption and make lasting, meaningful photographs.

He grew up in the Black Country in the English Midlands, attributing the sights and sounds of heavy industry as a major influence upon his imagery.

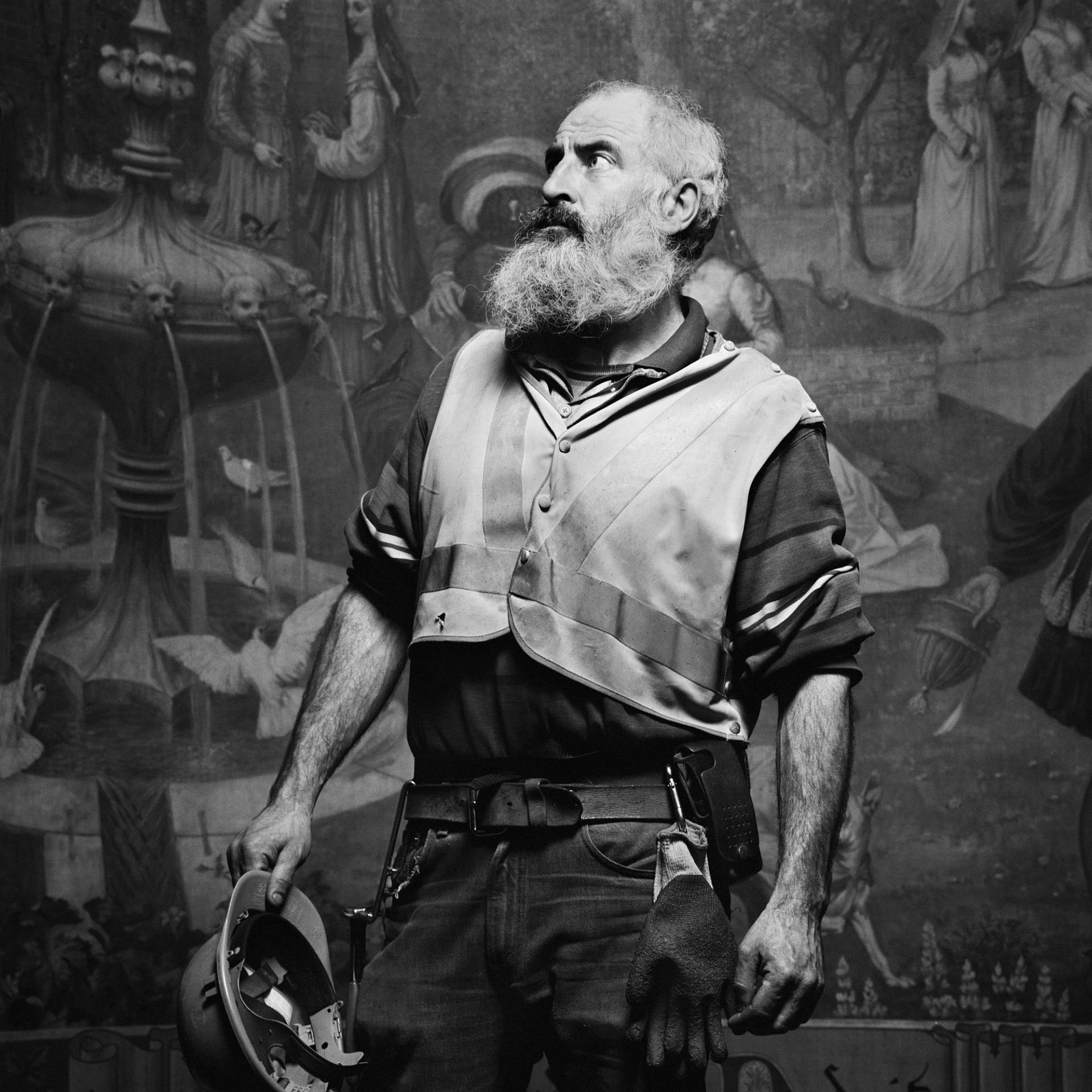

Brian Griffin, Liam, Steel Worker (2007). From the project Team Photo, for the opening of the Eurostar terminal at St Pancras station © Brian Griffin Estate

Griffin gave up a job at British Steel at the end of the 1960s to study photography at Manchester Polytechnic, where he met Parr and Daniel Meadows. Afterwards, he moved to London to begin his storied freelance career, taking a portfolio of photographs of ballroom dancers to Roland Schenk at Management Today. The celebrated Swiss art director immediately saw his potential and encouraged the young photographer’s flights of imagination in the most unlikely setting of corporate portraiture.

His personal documentary work featured in landmark exhibitions in the 1970s, when Britain’s art establishment began taking photography seriously, including Hayward Gallery’s first major survey of contemporary practice, Three Perspectives (1979). The 1980s were, however, his undoubted peak. Indeed, the Guardian hailed him “the photographer of the decade”. Many of his most famous images of musicians (Kate Bush, Siouxsie Sioux and Elvis Costello, to name but a few) were made during this time, as was his most memorable large-scale commission, celebrating the completion of the Broadgate project in the City of London.

Brian Griffin, Rush Hour, London Bridge (1974). Commissioned by Roland Schenk for Management Today © Brian Griffin Estate

He was widely recognised for Work, published in 1988, one of many often self-published books he produced throughout his career. And following an exhibition at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in 1987, alongside the first showing of Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency outside the US, dozens more shows followed, at home in the UK and across Europe.

Throughout the 1990s, Griffin worked primarily as a director of TV commercials and music videos, returning to photography in 2002 and picking up where he left off, shooting memorable campaigns for Reykjavik Energy, the completion of the HSI railway, the city of Marseilles, and a prized commission for the London Olympic Games in 2012. And among the dozens of books and shows he produced over the past 15 years, there were retrospectives in the UK, Iceland, Italy and Georgia. In 2021 he published what was to be the first half of his autobiography, Black Country Dada, designed by Cafeteria, with whom he was planning to do the second part later this year.

“This remarkable generation came out of Manchester Polytechnic, which included Brian and Martin Parr and Daniel Meadows,” says the collector and gallerist James Hyman, who founded the Centre for British Photography. “And the three of them have been absolutely fundamental, in their different ways, in the development of British photography over a 50 year period. He's got a central place in that history, and he was also a very individual voice.”