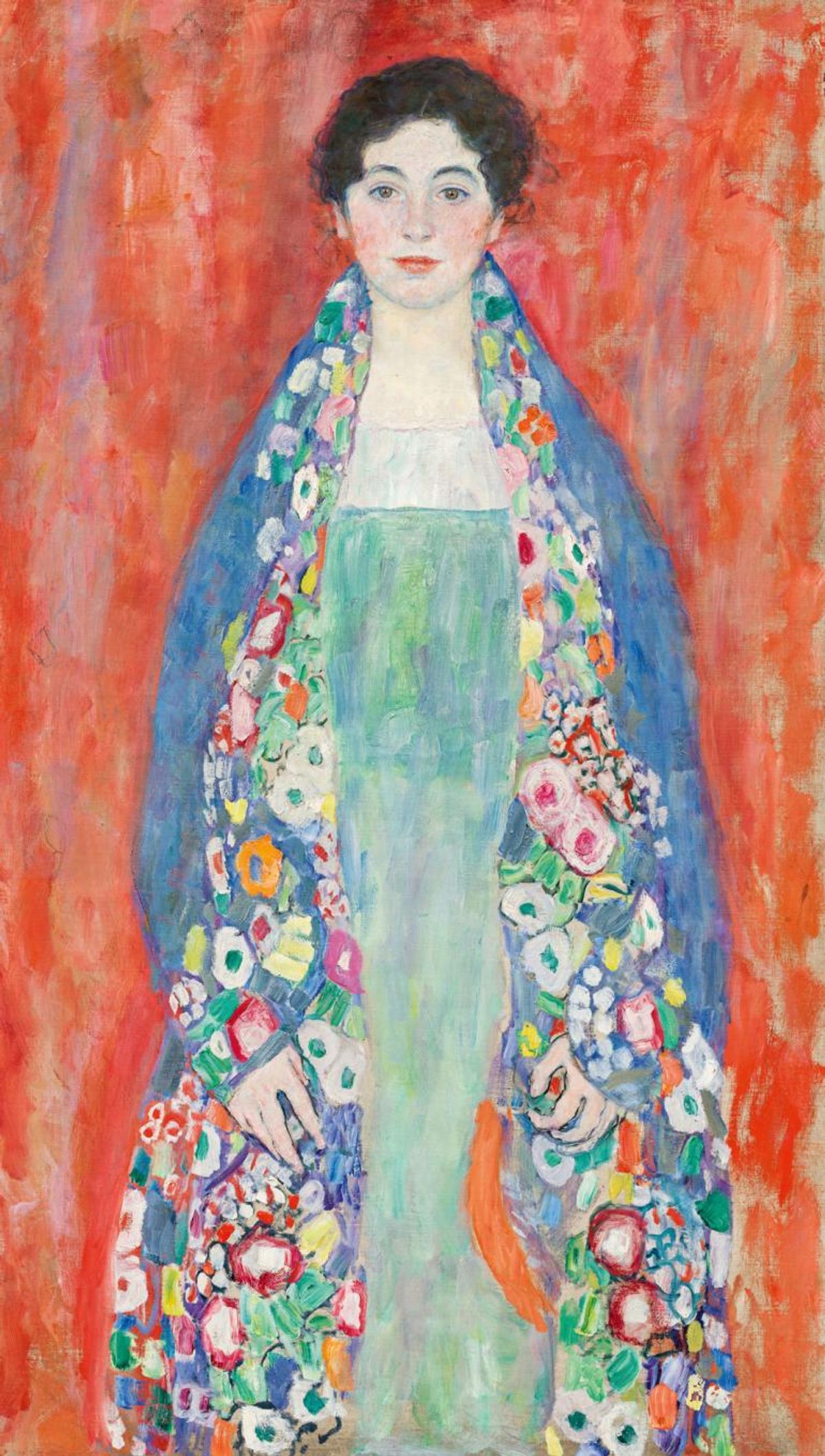

A late portrait by Gustav Klimt that was hidden in private ownership and believed lost for decades is to be auctioned in April in Vienna after the current owner reached a settlement with the heirs of the family that commissioned the painting.

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, dating from 1917, is expected to fetch between €30m and €50m at the Vienna auction house Im Kinsky on 24 April. Before the sale, it will be exhibited in locations including Switzerland, Germany, Britain and Hong Kong.

“The rediscovery of this portrait of a woman, one of the most beautiful portraits of Klimt’s final period of creativity, is a sensation,” Im Kinsky said in a statement. “While the picture is documented in Klimt catalogue raisonnées, it was only known to art historians as a black and white photograph.”

Very little is known about the provenance of the portrait before 1960. The name of the person who commissioned it from Klimt was documented only as “Lieser”—a family of important Jewish industrialists in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was long believed that the painting was commissioned by Adolf Lieser and portrayed his daughter.

However, there are some indications it could have been commissioned by Henriette Lieser-Landau, a friend of Alma Mahler’s and the ex-wife of Justus Lieser, Adolf’s brother, according to Ernst Ploil, one of the managing directors of Im Kinsky. Henriette, who was also a friend of the composer and author Alma Mahler’s and the ex-wife of Justus Lieser, had two daughters who could have been the subject of the painting. She was deported in 1942 and murdered in 1943 by the Nazis, Ploil told a press conference in Vienna.

“What is for sure is that the painting was still in Klimt’s studio at the time of his death” in 1918, Ploil said, and it is not quite finished. After Klimt died, it is presumed to have been delivered by the executors of his will to whoever commissioned it.

The art historian Otto Kallir Nirenstein planned to exhibit the work in a Klimt show in 1925, and the photograph of the painting, now in the Austrian National Library, was likely taken for that exhibition, the auction house said.

But beyond that, the painting’s traces disappeared—until now. It has changed hands via bequest three times since the 1960s. Unusually, “there are no stamps or stickers on the back of the painting,” which was completely pristine and original, Ploil said.

In negotiations with the Lieser heirs, the auction house “assumed a worst-case scenario,” Ploil said—that the painting was unlawfully expropriated during the Nazi era, but there was no evidence of this. The heirs will receive a share of the proceeds from the auction, he said.

The sale in Vienna is a rare occurrence—given the international interest in Klimt and the high prices paid for his work, on the occasions when a painting is offered for sale it is usually handled by the big auction houses and sold in New York or London.