Two of the UK’s leading national museums have signed a loan agreement with Ghana to return gold regalia that was looted during military operations in the 19th century. The British Museum (BM) and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) have made the arrangements with the Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, the capital of what was then the Asante (Ashanti) empire.

The 32 items are nearly all royal regalia, much of it made with gold. Most of the pieces will be seen in Ghana for the first time in 150 years.

The deal was arranged when the current Asantehene (king), Osei Tutu II, visited London in May last year. On that occasion he met the directors of the BM, Hartwig Fischer, and the V&A, Tristram Hunt. The Asantehene’s two advisors, the former BM curator Malcolm McLeod and the Ghanaian historian Ivor Ageyeman-Duah, were also present, having played a key role behind the scenes.

A meeting of kings: Asantehene Osei Tutu II at an audience with King Charles III at Buckingham Palace, 4 May 2023. On his London visit, the Asantehene also met with the British Museum and the V&A to finalise the loan arrangements © PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo

The May meeting took place three months before the BM announcement about a massive theft of Greek and Roman antiquities, which led to Fischer’s resignation. Mark Jones, the current interim director, has since finalised the arrangements.

The two UK museums are legally unable to deaccession, so the objects are being returned as long-term loans. Initially this will be for three years, but the loans are likely to be normally renewed, providing all goes smoothly.

The Kumasi museum, in the royal compound, was opened in 1995 and then closed for refurbishment in 2021. It is expected to reopen in April, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the present Asantehene’s reign. This year also marks 150 years since the 1874 punitive expedition which resulted in the looting of the royal palace. There was a later British military operation in 1896 which led to further looting.

Ceremonial knife and sheath, 18th or 19th century, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

A joint statement by the BM and V&A acknowledges that the objects seized had “cultural, historical and spiritual significance to the Asante people”. The seizures are also “indelibly linked to British colonial history in West Africa”. Some looted items formed part of a British indemnity payment forcibly extracted from the Asantehene, while others were sold at auction and later dispersed among museums and private collectors.

The V&A is lending 17 items, which include all 13 pieces acquired at a London auction in April 1874 of gold objects which had been looted during the February raid on the royal palace. These pieces include three gold soul discs, seven gold ornaments, a silver straining spoon and a pair of silver anklets.

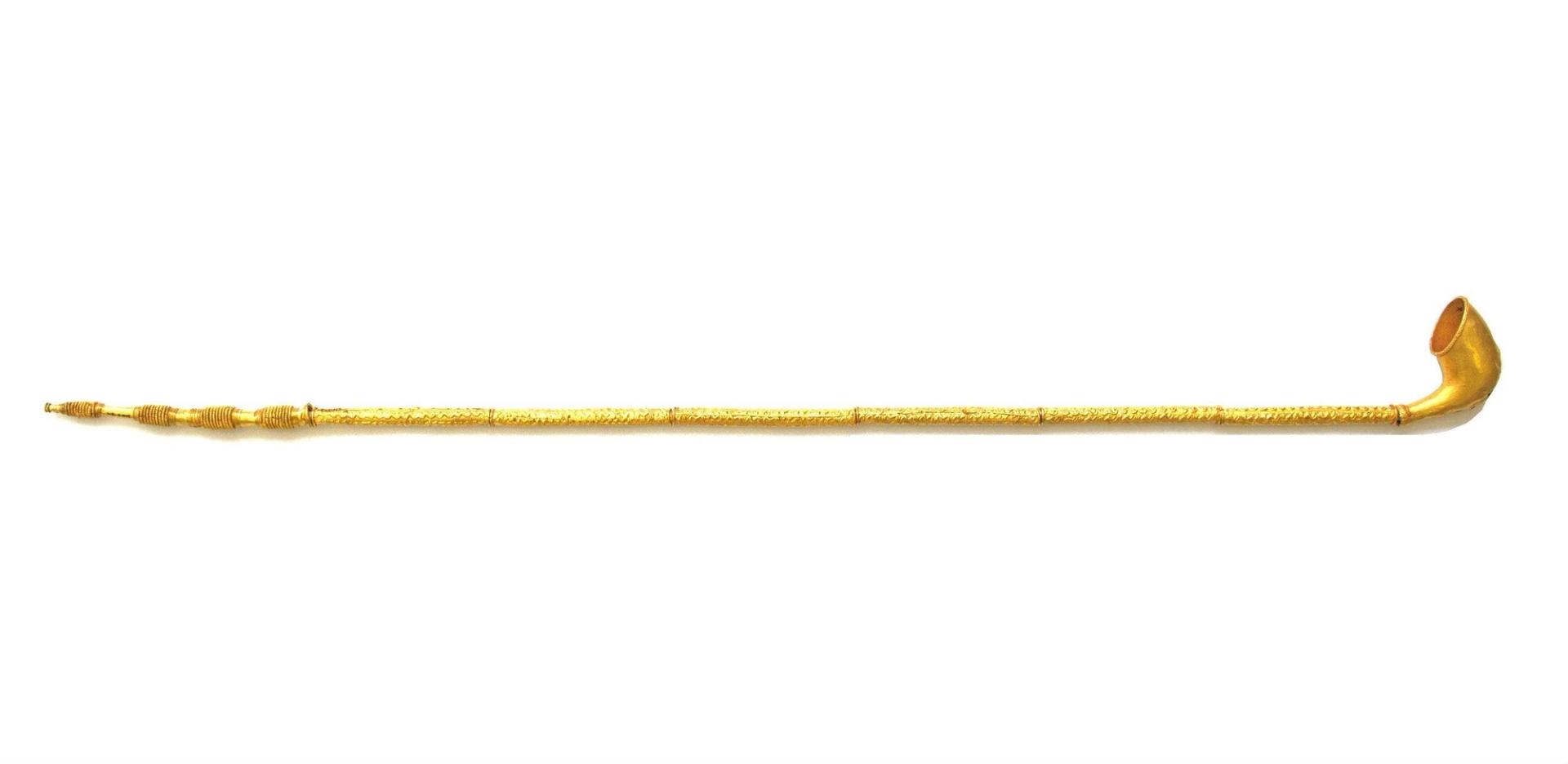

This gold peace pipe, made before 1874, cost the V&A £85 when it was bought at auction at Garrard’s, the London crown jewellers © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Among the auctioned items is a gold peace pipe, which would have been smoked with tobacco in the presence of the Asantehene to welcome visiting diplomats. The pipe was the most expensive item bought at the London auction at the crown jewellers Garrard’s, costing the V&A £85. The soldiers who originally looted it at the royal palace presumably had no understanding of the significance of the peace pipe, seeing it as just a decorative gold item.

Four other V&A objects will also be returned: a gold ornament bought in 1874 from a military family, another gold soul disc purchased in 1883, a gold ring donated by a collector in 1921 and a gold ornament depicting an eagle given in 1936.

The BM is lending 15 objects, again mostly made of gold. They include a sword armature, a ring, a sheath ornament, a knife, two swords, two caps, two necklaces and four soul discs. Four of these items were acquired in 1874-76, seven in 1900-02 and the latest was a necklace bought in 1942 from a London silversmith for £42.

Gold disc, pre-1874, Victoria & Albert Museum © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Among the most interesting objects from the BM is a gold miniature lute-harp ornament. In 1817, long before most of the British-Asante wars, this was presented by the then Asantehene to the UK diplomat Thomas Bowdich, when he was in Kumasi to negotiate a trade treaty.

The items being returned on loan represent only a part of the Asante collections of the BM and the V&A, which comprise both looted objects and those acquired by legitimate means. But it should be stressed that the loans include most of the major works, not secondary items. This demonstrates the commitment of the two UK museums to righting some of the wrongs of the colonial period.

Hunt comments that “150 years after the attack on Kumasi and looting of court regalia, the V&A is proud to be partnering with the Manhiya Palace Museum to display this important collection of Asante gold work”.

Today’s announcement marks the completion of a very lengthy process, which began in 1974, 50 years ago, when the then Asantehene contacted the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to ask for assistance to “secure the return of regalia and other items removed from our country by British expeditionary forces in 1874, 1896 and 1900”.

A few months later in 1974 McLeod joined the museum as keeper of ethnography. In 1981 he organised an exhibition in London of Asante objects and developed cooperative ties with Kumasi colleagues. Although McLeod left the BM in 1990, he has continued to work on facilitating the loans. The agreement also needed to await the current upgrading of the Manhiya building.

With the loan arrangement, the Kumasi museum (and therefore the Asantehene) is in effect acknowledging legal ownership of the objects by the two UK museums. This was essential, since the BM and V&A are both prohibited from deaccessioning.

Today’s announcement is likely to impact on other African restitution claims against the BM and the V&A, particularly those from Nigeria and Ethiopia. Arguably, the Ghanaian agreement will help provide a template for the return of objects seized in the military operation against Benin in 1897 and in the battle against the Ethiopian emperor at Maqdala in 1868.