From Harlem to Hollywood, Modernism in all its forms was on firm footing in much of the US during the first half of the 20th century, with the exception—or so it has seemed—of the American South. Mired in the Jim Crow laws that kept Black and white citizens living in what amounted to different nations, and lacking everything from widespread electricity to major museums, the south was viewed as a bulwark of the anti-Modern. Now, a new touring exhibition offers up a counternarrative.

With just over 100 works by southern artists as well as northern artists encountering southern life, Southern/Modern will open this month at Nashville’s Frist Art Museum before heading to the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis and the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is at the latter that the curator Jonathan Stuhlman has been planning the show for a decade.

The Frist version opens with a section called simply “Southerners”. Using a number of portraits and genre scenes that conjure up settings from rural South Carolina to anything-goes New Orleans, the Frist immediately strives to “de-exoticise the national imaginary” that has long coloured the way Americans view their lower-right quadrant, says Mark Scala, the museum’s chief curator. And in the process, it succinctly reveals how the American South fostered a set of distinct variations on the Modernist mindset.

Evening (1940-41), an oil-on-burlap work by South Carolina’s William H. Johnson, sets the tone. Depicting a sharecropper couple at home, the painting is marked by naive geometry and primary colours, reflecting the African American artist’s interest in European Expressionism while channelling American folk-art motifs. Elsewhere, there will be a pastel-on-paper work by the New Orleans-based northerner Will Henry Stevens, whose untitled piece from 1944 transforms a turn in the woods into a Kandinsky-like maelstrom.

Black Mountain College in North Carolina was the exception to every rule about cultural life of the south. Active from 1933 to 1957, it was America’s answer to the Bauhaus school. The show will feature work by Black Mountain’s Bauhaus luminary, Josef Albers, as well as Black Mountain #6 (1948), an abstract painting by Elaine de Kooning, who spent a few months there in the late 1940s.

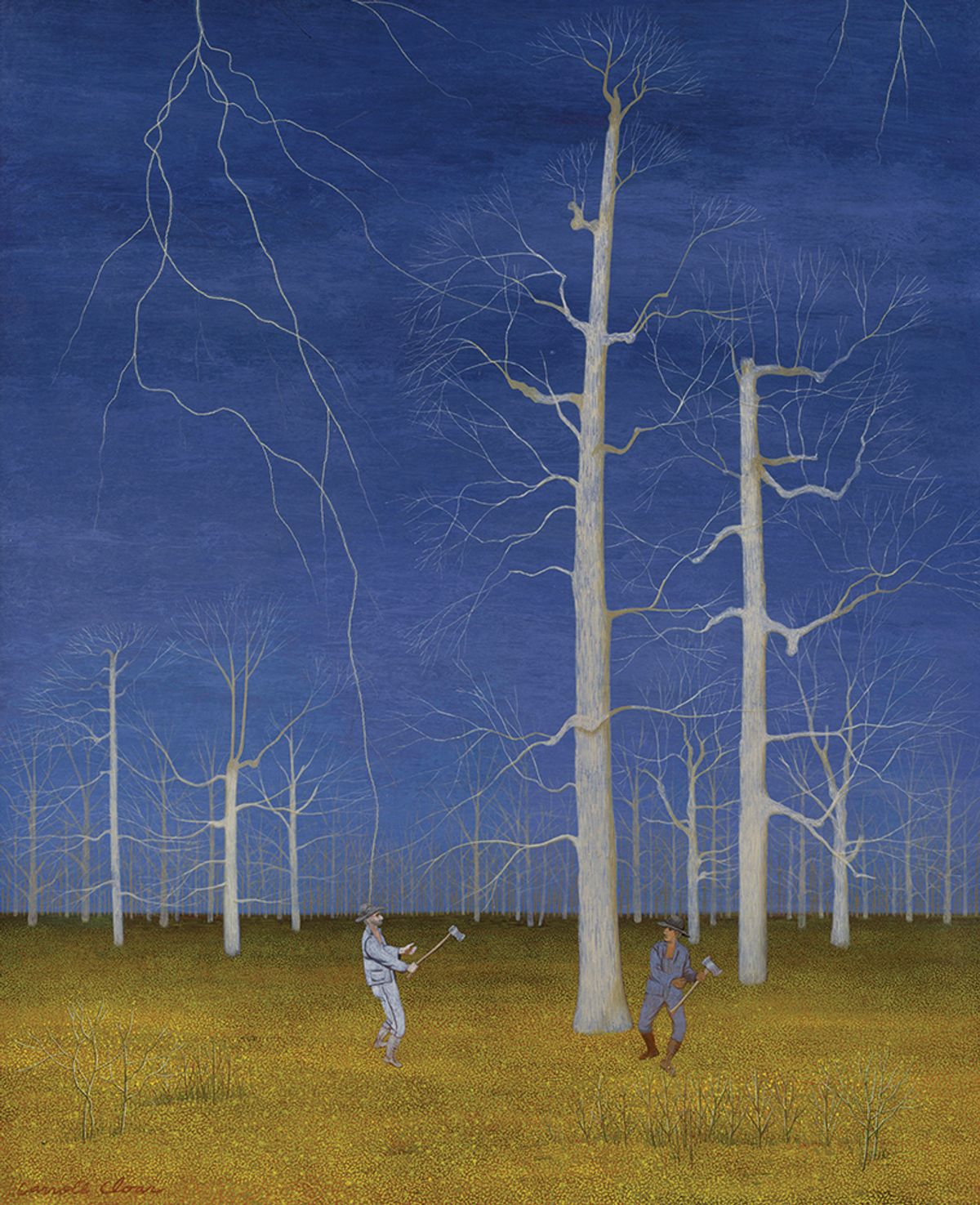

The south did foster major figures such as Jasper Johns, a Georgia native who left for good in his early 20s and seemed to never look back. However, Southern/Modern recalls figures who did the opposite, such as Carroll Cloar. Born in 1913 in Arkansas, Cloar studied in New York and travelled the world before settling in Tennessee in the mid 1950s. An obsession with rural landscapes marks much of southern art and Cloar’s The Lightning that Struck Rufo Barcliff (1955), on loan from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows how a Modernist eye working with southern subject matter can create something unique. Based on a story about an unlucky logger in the Arkansas Delta, the painting fuses Surrealism and Regionalism to depict the natural world as both wondrous and dangerous, and the southerners themselves as its mere playthings.

• Southern/Modern, Frist Art Museum, Nashville, 26 January-28 April