The multidisciplinary work of the Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican artist Alia Farid explores what she describes as the “complex and fragmented histories” of these regions, and how styles, symbols, rituals and social devices coalesce across continents. This can involve filming a fishermen’s festival on the island of Qeshm in the Persian Gulf, installing an orchard of replica date palms made from mechanical components on the terrace of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art or making giant resin sculptures in the form of scaled-up Kuwaiti drinking fountains.

But whether she is writing, drawing, making films or creating sculptural installations in myriad media, Farid’s work is underpinned by a desire to foreground histories that have often been marginalised or obscured by the Global North. By examining specific communities and lived histories and focusing on local practices and traditions, Farid not only traces the movement of people, but also reveals how everyday objects, architectural styles and ornamentation have been shaped and adapted by colonial histories and the exploitation of natural resources. Farid has been nominated for this year’s Artes Mundi 10 prize, and for the award’s exhibition in Cardiff she is showing work about the impact—social, political, historical and ecological—of extractive industries on southern Iraq and Kuwait. She also currently has a solo exhibition at the Chisenhale Gallery in London, where she is showing new textile works depicting the Palestinian diaspora in Puerto Rico. As this year’s recipient of the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter museum’s Lise Wilhelmsen Art Award, she will have a solo show at the Norwegian museum in September 2024.

Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican artist Alia Farid

Photo: Djinane Alsuwayeh

The Art Newspaper: Your Chisenhale commission consists of 16 rugs, hand woven and embroidered in Samawa, southern Iraq, that depict businesses, buildings and shopfronts owned by Puerto Rico’s Palestinian population. These images of contact and convergence between cultures also seem to reflect elements of your personal heritage.

Alia Farid: I was born and spent my childhood years in Kuwait, and later lived in Puerto Rico. My parents wanted to raise my siblings and I with equal emphasis on both cultures. We lived back and forth. But in 1998 I moved to Puerto Rico for 11 years. I finished high school in Puerto Rico and then started studying art there. Through my family I met members of the Arab diaspora in Puerto Rico, and in conversation began seeing parallels between the two regions. Although this project was developed much later, it’s familiar.

The images on the rugs present a striking alternative to the usual tourist images of Puerto Rico and its people.

As a younger artist I wasn’t readily included in shows on art from the Caribbean, Latin America or the Arab world. I remember a lot of my artist friends who lived consecutively in any of the regions were, and I remember feeling a bit left out. Maybe it’s because my work doesn’t fulfill expectations of what art from a certain region looks like, but I’m OK with that.

The Chisenhale rugs often display text that can combine different languages in one piece, which reminds me of you saying you grew up hearing Arabic spoken with a Spanish accent.

I think about the relationship between different languages as moments of proximity and distance. And in weaving different languages, or drawing the writing, how the relationship between writing and drawing is destabilised.

Different cultural, historical and political perspectives also coalesce in In Lieu of What Is, your five giant water fountain sculptures on show at the National Museum Cardiff as part of Artes Mundi. Made from lacquered fibreglass, they take the form of vessels ancient and modern, many of which also echo the shapes of public drinking fountains in cities throughout Kuwait.

Just driving around Kuwait I became interested in these drinking fountains that relate to a long tradition of offering water in the desert. Before oil was discovered, people in the area got their drinking water mostly from the Shatt al-Arab river at a time when relations between Iraq and Kuwait were less hostile. Since the Kuwaiti-Iraq war, the border between Kuwait and Iraq has become very strict, and Kuwait is now mostly dependent on water from desalination plants, which is a huge strain on the environment. The vessels and the new material culture they represent are part of a group of works I’ve been developing on both sides of the Kuwait-Iraq border.

You have taken some of the existing water fountains from Kuwait that riff on traditional vessels, but you have also made your own addition in the form of a giant replica of the ubiquitous plastic water bottle used across the globe.

Each of the vessel shapes holds information about the cultural and trade networks of the region. The lota, for example, is a vessel more commonly seen in South Asia, and then there’s a juglet from the Levant, a jerrycan for carrying holy water which I really like because of how it represents Saudi Arabia’s relationship both with religious tourism and oil. Installed all together, the vessels create this map of networks. The plastic bottle is a way into the project for people who are less familiar with some of the other vessel shapes. Plastics and resins are byproducts of oil, and yes, partly I’m interested in the provenance of the vessel shapes but also the provenance of materials and material entanglements.

Farid’s In Lieu of What Is (2022)

Photo: Polly Thomas

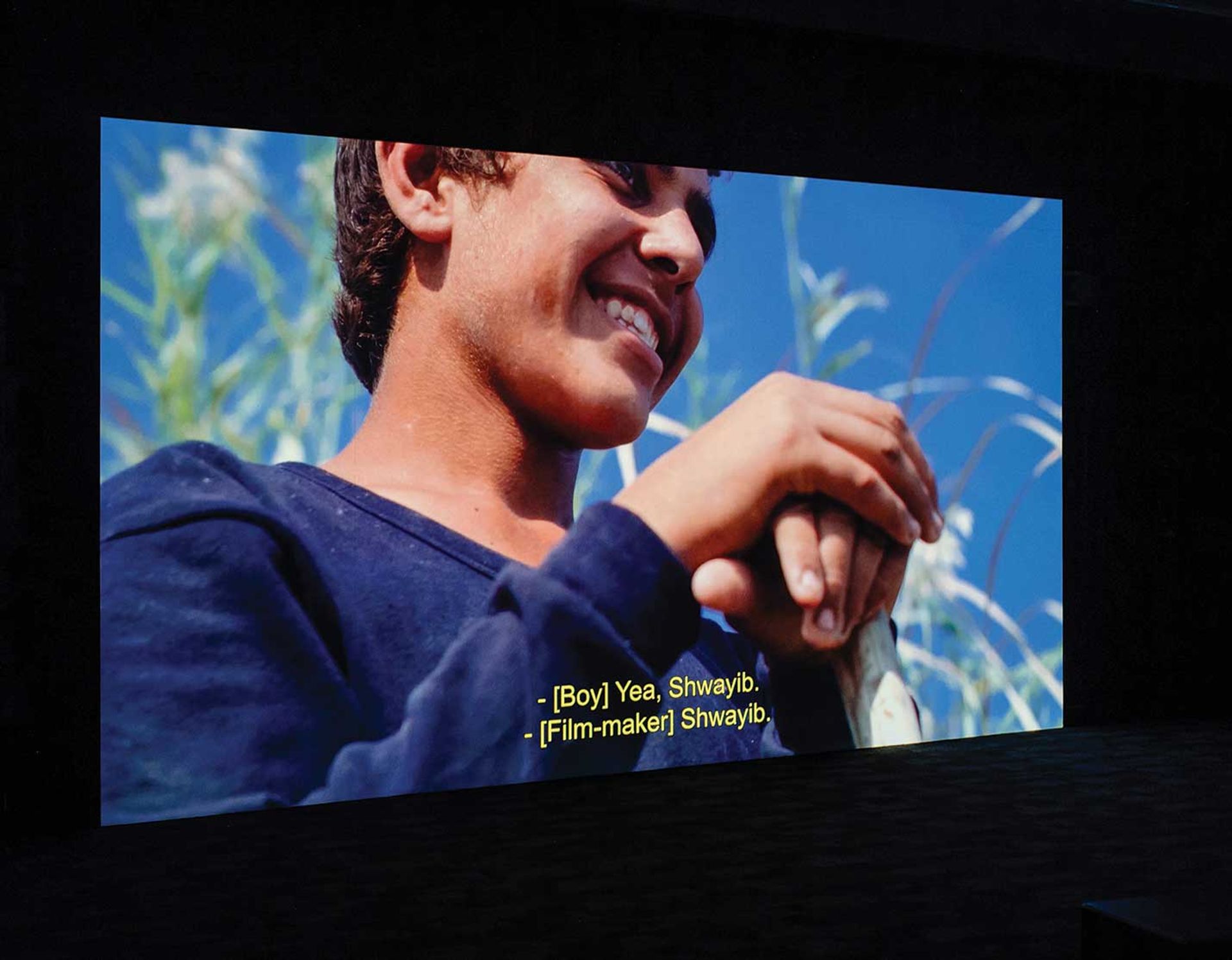

The confluence of water and oil is at the centre of Chibayish, a film originally commissioned by the Whitney Biennial in 2022. A continuation of that work, also titled Chibayish and commissioned by the Vega Foundation, was made with the people of the marshlands of southern Iraq and is on show in Cardiff.

The Iraqi marshes at the confluence of the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers is one of the most important wetland ecosystems in Asia. Beneath its subsoil are some of the biggest oil reserves in the world, which is the main reason for the marshes’ many waves of destruction. The film is not scripted, it is a long conversation and collaboration between [my] film-maker friend Muhammed Al Mubarak from Bahrain, our friends in Chibayish and myself. On my Kuwaiti side, my paternal grandmother is from southern Iraq. Crossing that border for the first time was an important moment in my life. I think it’s important for people to remember that we are not our governments, that these borders are not real and to insist on community and connectivity.

Farid's Chibayish (2022)

Photo: Polly Thomas

The Chisenhale tapestries are part of Elsewhere, another ongoing project that you describe as a growing material archive that maps Arab and South Asian migration to Latin America and the Caribbean. Cuba and Trinidad are your next areas of exploration—will this project continue to generate works in woven rug form?

Yes, that’s the idea. Elsewhere is about building up a volume of lesser-known stories. It’s a landscape project and I chose textile as a medium because of how much material information is contained in a woven work and what the materials say about conditions of the place. If you think about the fibres and wool and hairs that go into making a tapestry, the types of dyes, whether they are natural or artificial, it’s all information that can be studied. Elsewhere is landscape depicted but also landscape embedded.

Biography

Born: 1985 Kuwait City

Education: 2006 BA Escuela de Artes Plásticas de Puerto Rico; 2008 Master of Science in Visual Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2012 MA Museum Studies and Critical Theory, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona

Lives and works: Kuwait and Puerto Rico

Key Shows: 2019 Portikus, Frankfurt/Main; 2020 Yokohama Triennale; 2021 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Brisbane; 2022 Kunsthalle Basel; 2022 Whitney Biennial, New York

• Alia Farid: Elsewhere, Chisenhale Gallery, London, until 4 February; Artes Mundi 10, National Museum Cardiff and other venues, until 25 February