Zanele Muholi: Eye Me

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 18 January-11 August

“The personal is the political” is a mantra embedded deep in the work of Zanele Muholi, the South African photographer and activist. This month their first major West Coast exhibition, Eye Me, opens at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA). It will features more than 100 photographs, along with paintings, sculpture and video from the last two decades.

Significant photographic series from their career will also be included, starting with Only Half the Picture (2002-06), which was made during visits to South African townships to document survivors of hate crimes against members of the queer community. Even though, in 2006, it was the first African nation to legalise same-sex marriage, violence against LGBTQ+ people persists. As Muholi has said in an interview with Tate: “We want to bring about change in spaces that are queer-phobic.”

Other work in the exhibition, such as Being (2006 onwards), will spotlights queer couples and their everyday interactions. Whether the subjects are clasped in full embrace, as in LiZa I (2009), or exchanging a gentle kiss in Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg (2007), these images capture moments of ease and tenderness. The series Brave Beauties (2014 onwards) depicts trans women, gender non-conforming and non-binary people.

In their more recent work, Muholi has tackled self-portraiture through deliberately exoticised and stereotyped female poses. In the double portrait Zazi I & II, Boston (2019), the artist has their hair piled high, with a round mirror held up to their darkened face. In the left image they look sideways, seen in profile; in the right image they look straight out at the viewer, reversing the gaze and making the viewer the object. It raises the question of who is defining whom.

“Muholi’s photography and activism have been inextricably bound together,” says Shana Lopes, one of the exhibition’s curators and assistant curator of photography at the museum. “Their work calls attention to the trauma and violence enacted on queer people while celebrating their beauty and resilience.”

Harold Cohen’s AARON Gijon (2007) will appear as part of the British artist’s exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, beginning on 3 February Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Digital Art Committee. Rights and reproductions © Harold Cohen Trust

Harold Cohen: AARON

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 3 February-June

The time feels right, not much more than a year or so into the new age of artificial intelligence (AI), for Harold Cohen to receive a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, along with his ground-breaking drawing and painting program, AARON, which Cohen developed over four decades. He was an early scholar in AI at Stanford University in California, as well as being one of the most compelling pioneers in computer art.

The British-born artist had been a noted tutor at the Slade School in London, held a one-man show at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1965 and represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1966 before moving to the US in 1968 to be a visiting professor at the University of California San Diego (UCSD). Cohen—surrounded in California by the generation who went on to shape Apple and other Silicon Valley giants—was first attracted to coding as an intellectual exercise before realising that drawing in code helped him to address the challenges he saw for artists who are continually in search of new forms.

Harold Cohen: AARON will draw on the museum’s rich holdings of AARON’s delicately plotted and coloured paintings and drawings, along with two versions of the software that will be used to show its drawing process live in the Whitney’s galleries.

Constantin Brâncuși’s sculpture La Muse endormie (1910) will be on show at the Centre Pompidou in Paris from 27 March to 1 July © Photo CNAC/MNAM Dist. RMN Adam Rzepka

Brâncuși

Centre Pompidou, Paris, 27 March-1 July

Constantin Brâncuși’s Parisian studio was a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, in which the relationships between sculptures in space were as vital as the daring, minimal forms themselves. While he returned again and again to certain themes in his work—the bird in space, the kiss, the endless column—the Romanian-born artist constantly remixed “mobile groups” of sculptures in the studio. So important were these ensembles that when Brâncuși stopped producing new work in his final years, he replaced any pieces that were sold with plaster copies.

The fate of the studio has been entwined with the Centre Pompidou since the museum opened in 1977. Brâncuși bequeathed the entire contents of his rooms in Impasse Ronsin, a Montparnasse artists’ colony, to France shortly before his death in 1957. While the original studio was demolished a few years later, its replica has endured, housing 137 sculptures (and 87 bases) in the exact layout that Brâncuși left them. After a flood scare in 1990, the reconstruction moved into Renzo Piano’s purpose-built annexe opposite the Pompidou in 1997. Now, as the museum prepares for a complete closure and renovation in 2025, it is remixing Brâncuși’s cluttered space once again.

The artist’s bequest of sculptures, photographs, drawings, films, archival documents, tools and furniture is the “backbone” of what the Pompidou calls an “exceptional” exhibition—the first in France for a generation—dedicated to the “inventor of modern sculpture”. With nearly 200 sculptures from all the key series, the show will display studio plasters alongside the stone or bronze originals, borrowed from collections around the world. The exhibition promises to shed light on Brâncuși’s process of direct carving and creative inspirations including Romanian folk architecture, Cycladic art and a short-lived apprenticeship with Auguste Rodin. Quitting the master’s studio after a month in 1907, Brâncuși set up on his own and never looked back.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Greifswalder Hafen will be in the Infinite Landscapes exhibition at the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, from 19 April Photo: Jörg P. Anders

Caspar David Friedrich: Art for a New Era

Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Until 1 April

Caspar David Friedrich: Infinite Landscapes

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 19 April-4 August

Caspar David Friedrich: Where it All Started

Albertinum and Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden, 24 August 2024-5 January 2025

Germany’s culture tourism industry is hoping to cash in on Caspar David Friedrich’s 250th birthday this year with a trio of major exhibitions planned in Hamburg, Berlin and Dresden, the three cities with the best collections of his work worldwide.

Hamburg’s Kunsthalle kicked off the festivities late last year with Art for a New Era, an exhibition focused on his landscapes and Romanticism’s portrayal of man’s relationship with nature. Among the 60 Friedrich paintings in the show are perhaps his most reproduced work, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (around 1817), and Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (1818), a loan from the Oskar Reinhart Foundation in Winterthur. The show also explores Friedrich’s impact on contemporary art with works by Olafur Eliasson, Kehinde Wiley and Julian Charrière, among others.

Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie opens Infinite Landscapes on 19 April and will examine its own role in rediscovering the artist—who had by then faded into obscurity—at the beginning of the 20th century. It will also explore his pairs of paintings, such as The Monk by the Sea and The Abbey in the Oakwood (both 1808-1810). A third section of the show will present the latest research into his technique.

In Dresden, where Friedrich lived for about 40 years and produced most of his best-known works, the Albertinum and the Kupferstich-Kabinett will show Where it All Started from 28 August. The exhibition at the Albertinum will put his work alongside the Old Master paintings that inspired him. The museums have created a portal on their Friedrich events (cdfriedrich.de), while festivities are also planned in his city of birth, Greifswald (caspardavid250.de).

Michelangelo’s Virgin and Child with the Infant St John the Baptist (The Taddei Tondo) (1504-05) at the Royal Academy of Arts

Michelangelo: the Last Decades

British Museum, London, 2 May-28 July

Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael

Royal Academy of Arts, London, 9 November-16 February 2025

With significant Michelangelo holdings in its national collections, the UK is well placed to stage exhibitions of the master’s work; and like London buses, two have come along at once. In May the British Museum is mounting Michelangelo: the Last Decades, which covers the monumental achievements of his last 30 years. And in November, the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is pitting Michelangelo against his fellow artist Leonardo da Vinci, and looking at their influence on the younger Raphael.

The British Museum show takes as its cue Michelangelo’s relocation to Rome in 1534 after the collapse of the Florentine republic. He took up a series of papal commissions, including The Last Judgement fresco in the Sistine Chapel, the rebuilding of St Peter’s Basilica and the creation of the wall paintings in the Vatican’s Pauline chapel. To illustrate this late surge of productivity, the British Museum is unveiling the Epifania cartoon (around 1550), which has been undergoing restoration since 2018, alongside preparatory drawings for The Last Judgement, architectural designs for St Peter’s and a selection of his writing.

In contrast, the RA’s show focuses on direct Michelangelo-Leonardo rivalry, when the pair were commissioned in 1504 to paint battle scenes on opposite walls of the Palazzo Vecchio. Neither Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina nor Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari were finished, and what remained was subsequently lost. The RA are pulling together relevant work: their own Taddei Tondo, Michelangelo’s unfinished circular relief of the Virgin and Child and St John the Baptist; and Leonardo’s celebrated Burlington House Cartoon, of the same subjects (plus St Anne). The RA owned the latter work until putting it up for sale in 1962. Normally displayed in the National Gallery, it will have a homecoming of sorts.

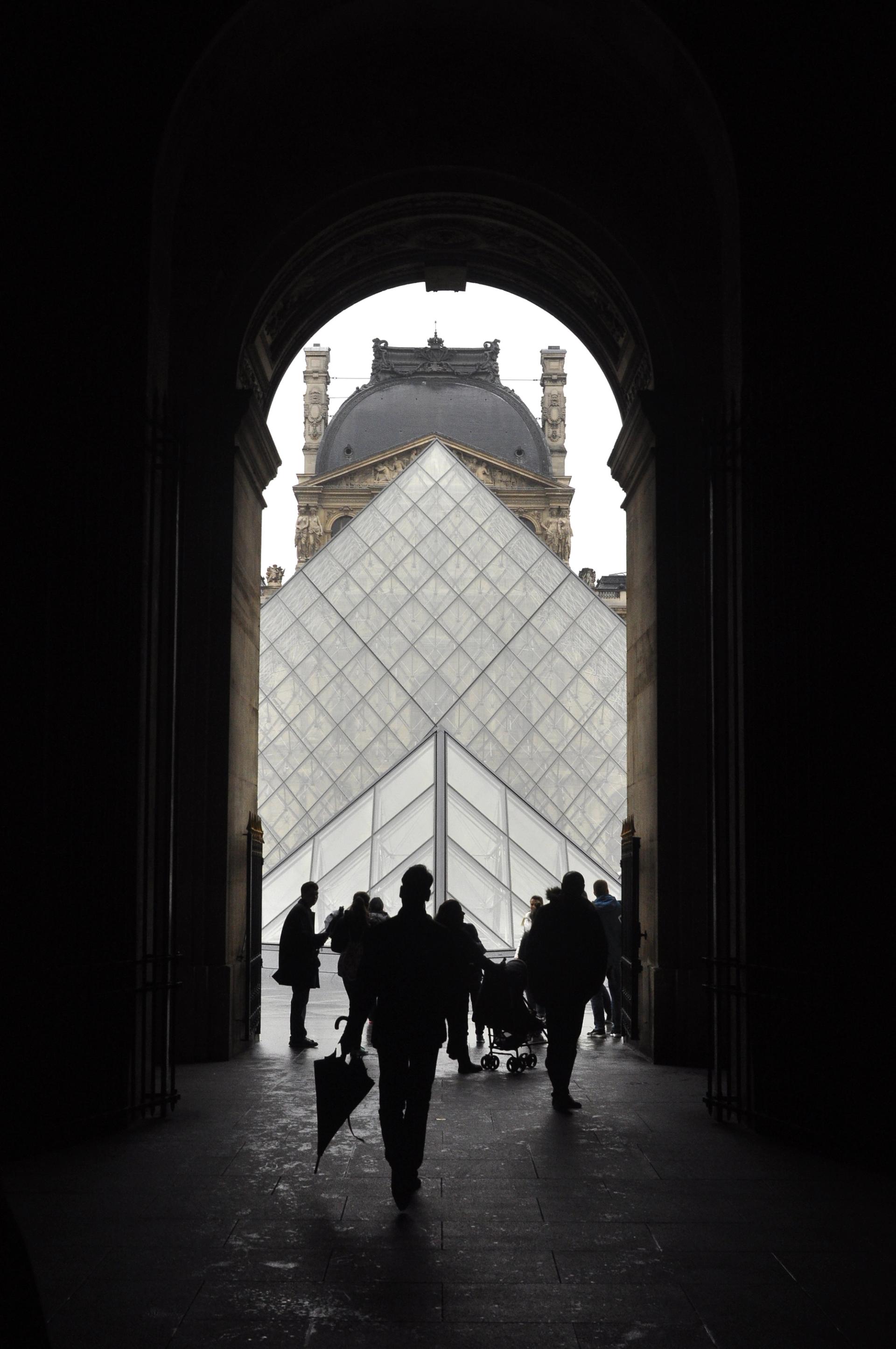

The architect I. M. Pei is being celebrated by M+ Museum in Hong Kong, starting 29 June, for his works, such as the East Building at Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art and the pyramid entrance to the Louvre in Paris Photo: Guillermo R. Vallejos / Shutterstock

I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture

M+ Museum, Hong Kong, 29 June-31 January 2025

The man who brought pyramids of glass and angular atria to some of the world’s most important museums is getting his first full survey this year. The Chinese-American architect I. M. Pei (1917–2019) is remembered in the art world for his East Building of Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art (1978), Qatar’s Museum of Islamic Art (2008) and—of course—the striking pyramid entrance to the Musée du Louvre in Paris (1989).

These and other high-profile projects have seen Pei lauded as one of the greatest architects of the 20th and 21st centuries. “His life and work weave together a tapestry of power dynamics, geopolitical complexities, cultural traditions and the character of cities around the world,” according to a statement from the museum. “[His] transcultural vision laid a foundation for the contemporary world.”

Co-organised by Shirley Surya, the curator of design and architecture at M+, and Aric Chen, the general and artistic director of the Het Nieuwe Instituut in the Netherlands, the exhibition has been five years in the making. It will include architectural drawings, sketches, videos and other archival documentation, much of which will be on view for the first time, while architectural models will show Pei’s projects. Newly commissioned photographs of his buildings by contemporary photographers will also go on display.

The 1962 Barbie Dream House will be in the Design Museum’s exhibition starting 5 July Photo: Mattel, Inc

Barbie

Design Museum, London, 5 July-23 February 2025

Hold on to those bright pink outfits: just when you thought Barbiemania was over, a major exhibition of the world’s most famous doll will be part of the 65th anniversary celebrations of the brand. Working in partnership with Mattel Inc, the Design Museum curator Danielle Thom and her team have been granted special access to the Barbie archives in California. The exhibition will “map the Barbie legacy that started in 1959 when Ruth Handler wanted to craft a different narrative for her daughter, Barbara” and includes dozens of “rare and unique items” alongside other key loans.

Being a Design Museum show, there will be a focus on the “world” of Barbie: from fashion and architecture to furniture and vehicle design. For example, Barbie’s 1962 Dream House, with its bright yellow walls and mid-century modern furniture, will go on display. And, of course, there will be dolls, both familiar and never-before-seen: the 1985 Day to Night Barbie, where the pink power suit transforms into an evening gown, will be included. Vogue notes the ensemble is “a nod to the women’s workplace revolution” and points out that Margot Robbie referenced both looks during the Barbie movie press tour. “Barbie is one of the most recognisable brands on the planet and her story evolves with each new generation,” says the museum’s director Tim Marlow.

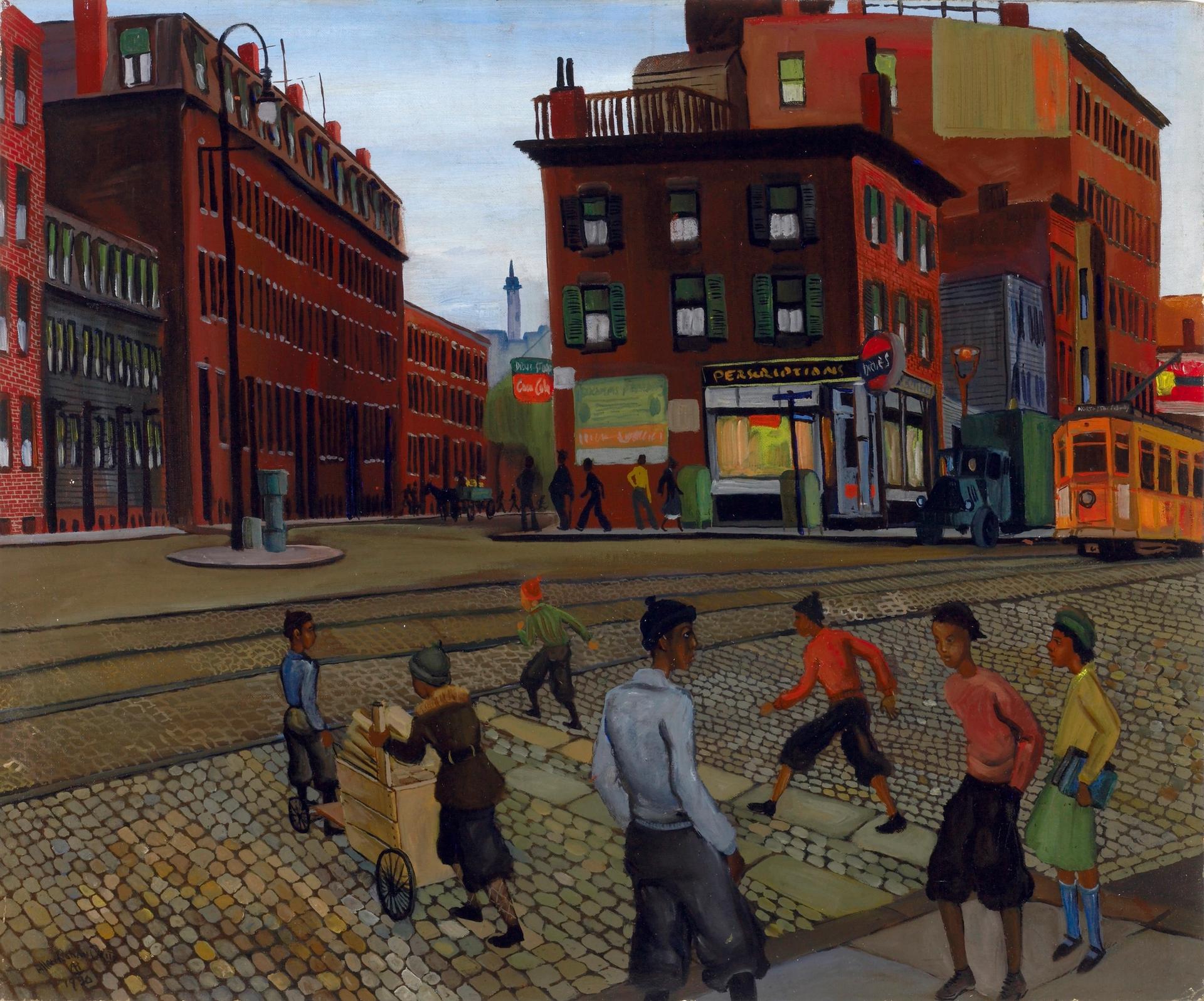

Allan Rohan Crite’s Douglass Square will be in The Work of Art: the Federal Art Project, 1935-43 exhibition at the Saint Louis Art Museum until February 2025 Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of the Federal Works Agency, Work Projects Administration 354:1943

The Work of Art: the Federal Art Project, 1935-43

Saint Louis Art Museum, 2 August 2024-16 February 2025

During the Great Depression, the US government went into the business of subsidising artists on a massive scale. The Federal Art Project was launched as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) and was a signature achievement. The main goals of the programme were to give work to unemployed artists and beautify a range of public buildings. America’s New Deal-era murals, in places like post offices and schools, can often still be seen, but the movable artworks have largely disappeared inside the storage depots of museums. This summer, the Saint Louis Art Museum will bring around 60 of its works from this period together, creating its biggest showcase in some 50 years.

While other museums may have larger collections of this type of art, Saint Louis is notable for the geographic diversity of its holdings. Major art centres of the era, such as New York and Chicago, are represented, but so are smaller cities like Milwaukee and Memphis.

Largely made up of works on paper, with an emphasis on US artists, the show recalls their lives and often brief careers. After the project ended, many went back to work as anything from bricklayers to janitors. The artist Dox Thrash is the best-known figure, but the show will also be rich in rediscoveries, like Selma Day, who spent most of her working life as an interior decorator.

Giuseppe Penone’s Essere Vento (To Be Wind) (2014), a sculpture of his hand with two grains of sand, will be part of the Arte Povera exhibition Photo courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, Giuseppe Penone © ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Arte Povera

Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 25 September-24 March 2025

A survey of Arte Povera at the Bourse de Commerce—Pinault Collection in Paris will be “90% Arte Povera and 10% what came before and after”, says the exhibition’s curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev.

The exhibition will primarily focus on the Italian movement, which embraced lowly materials such as old clothes and earth, through the works of 13 key figures including Giovanni Anselmo, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Jannis Kounellis, Mario and Marisa Merz and Giulio Paolini. But it will also trace the “precursors to Arte Povera, going as far back as the [eighth and third century BC] Etruscans looking at this idea of energy and constant metamorphosis,” says Christov-Bakargiev. “At the other end of the show, I aim to demonstrate how Arte Povera connects to what so many artists are doing today worldwide—how David Hammons connects to Jannis Kounellis, for example.”

The show will include works from the Pinault Collection along with loans from the Castello di Rivoli, which has rich holdings of such works following the acquisition of the dealer Margherita Stein’s collection in 2000 (many Arte Povera works in the Castello collection belong to the Italian bank foundation, Fondazione Arte CRT). Stein opened her gallery in Turin, known as Christian Stein, in 1966, exhibiting and collecting key Arte Povera works such as Lampadina (1962-66) by Michelangelo Pistoletto. The Paris exhibition will also include loans from several other leading public and private collections, both French and Italian, as well as pieces from living Arte Povera artists.

Christov-Bakargiev outlines how Arte Povera was revolutionary in other ways. “It’ll be a very alive exhibition. Life is in their art, reflecting the energy and vitality that runs through the cosmos. It’s not just about installing the works; you have to interpret them, rather like playing music. In a sense, these artists also invented installation art as we don’t always know where the boundary of the work is—a concept which moved Western art forward and resonates globally today.”

The curator also explains how the Turin landscape underpins the movement. “It is an industrial town in a flat area just below the mountains so there is this contrast [in the works] between the industrial modernity of Turin and the power of nature. It is not very often you see art in relation to the physical context from which it emerged.”

Duccio’s Madonna and Child (around 1290-1300) was acquired by the Met in 2004 for $45m, the most expensive acquisition in its history Image courtesy of The Met

Siena: the Rise of Painting, 1300-50

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 13 October-26 January 2025

Did European cultural life first shake off the Middle Ages in 14th-century Siena, rather than in 15th-century Florence? That is what museumgoers may take away from the autumn blockbuster at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Siena: the Rise of Painting, 1300-50.

Comprising some 90 artworks and other objects on loan from collections in the US and Europe, the show was inspired by the Met’s own expansion of its Trecento holdings over the past few decades, including the 2004 acquisition of Duccio’s Madonna and Child (around 1290-1300), whose apparent three-dimensional drapery belies its Byzantine sources.

The supreme work of the period, Duccio’s mammoth Maestà altarpiece, cannot make the trip from the hushed confines of its display back in Siena, in Tuscany. But, excitingly, the Met plans to reassemble all eight of the nine surviving panels of the work’s predella, or rear base, for the first time since they were dispersed in the 18th century.

Along with several works by Duccio, the exhibition will showcase works by Simone Martini and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. It makes the case that Martini (around 1284-1344), who left Italy to serve at the French court of the Avignon Papacy, took the Sienese School with him, and it includes works produced during the artist’s years in France.

In preparation for the show, the Met has initiated the first modern technical analysis of the Maestà and there are plans to publish the results in a separate volume around the time of the opening, says Stephan Wolohojian, the Met’s curator in charge of the department of European paintings.

Siena: the Rise of Painting, 1300-50 will later travel to London’s National Gallery, which is sending its three Maestà predella panels to New York, including Duccio’s pink-and-gold The Annunciation.

Käthe Kollwitz’s Ein Weberaufstand - Sturm (1897) will both appear at the SMK National Gallery of Denmark, one of three exhibitions in 2024 examining Kollwitz’s works

Kollwitz

Städel Museum, Frankfurt, 20 March-9 June

Käthe Kollwitz

Museum of Modern Art, New York, 31 March-20 July

Käthe Kollwitz

SMK – National Gallery of Denmark,Copenhagen, 7 November-25 February 2025

Käthe Kollwitz had an unflinching eye for the darkest moments of human experience. Whether portraying a mother’s aching grief at the death of a child or the poor being terrorised by hunger, her images of suffering have an intensely emotional charge that still reverberates a century after they were made.

Looking back on a lifetime of depicting the struggles of Germany’s working-class citizens and women, she wrote in 1941 of her reputation as a socialist artist. More than political conviction, the driving force was always the beauty she saw in her subjects. The workers “had a grandness of manner... Portraying them again and again opened a safety-valve for me; it made life bearable.”

The fusion of artistic experimentation and activism in Kollwitz’s indelible work will be a theme of not one but three major exhibitions dedicated to her in 2024. The first ever New York retrospective, at the Museum of Modern Art, will emphasise her “commitment to socially critical subject matter” against the prevailing turn towards abstraction. The Städel Museum in Frankfurt will consider her “desire to promote social change through her art”, says the curator Regina Freyberger, as well as the complex history of “political appropriation” that surrounded her legacy in the two Germanys after the Second World War.

And the National Gallery of Denmark is organising the first comprehensive display of Kollwitz’s “fundamentally humanistic” art in the country, says the curator Birgitte Anderberg. In its “pacifist stand, deep acknowledgement of inequalities [and] strong respect for women”, hers is art that stands the test of time.

Francisco de Zurbarán’s Saint François (1650-60), will be shown as part of the exhibition Zurbarán: an Icon of the Golden Age at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, running from 5 December to 2 March 2025 Photo: © Lyon MBA - Photo Alain Basset

Zurbarán: an Icon of the Golden Age

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, 5 December-2 March 2025

According to Franciscan myth, when Pope Nicholas V entered the crypt of the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, he came across the body of the long-dead saint standing upright and in the act of praying, with his eyes raised to the sky.

This striking image, beloved of artists over the centuries, is one that the Spanish Old Master Francisco de Zurbarán returned to several times. His takes on the subject are housed in museums across the world and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon will be bringing some of these together in Zurbarán: an Icon of the Golden Age.

Complementing the museum’s own Saint François (around 1650-60)—which was thought to have been given by Queen Maria Theresa of Spain to a Lyonnaise convent in the 17th century—will be two important earlier versions of the subject: Saint Francis of Assisi according to Pope Nicholas V’s Vision (around 1640) from the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya and Saint Francis (around 1640-45) from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It will be the first time all three works have been shown together along with pieces illustrating the developments of his subject matter.

Zurbarán’s commissions mostly came from religious orders and his use of chiaroscuro is thought to have been influenced by the work of Caravaggio and his circle. The Spanish artist had considerable success during this lifetime and although he was from Extremadura, he studied in Seville and was later invited to be the city’s official painter after its most famous artist son Diego Velázquez—who Zurbarán knew—left for Madrid.

In later life, as Zurbarán’s work fell out of fashion in Spain, he found a new market in the Americas, employing a larger workshop and exporting his religious paintings. Zurbarán’s influence on artists in the centuries following his death will also be explored in the Lyon show, as will the driving forces behind his own work.