In The South American Dream, Marcela Cantuária takes the opportunity to view her native continent from afar, painting familiar subjects for a new US audience. Born and currently based in Rio de Janeiro, she began focused on Brazil and moved outwards, tracing the history of activists, artists and leaders whose stories she finds influential.

All the works in the show were commissioned by the Pérez Art Museum Miami, and Cantuária created them with the institution’s galleries in mind, weaving individual pieces into an installation. Faced with the challenge of representing her connection to the land and people of South America for her first solo show in North America, Cantuária incorporates the spiritual and political, resulting in a balance that she believes makes the world a more meaningful place. The Art Newspaper caught up with Cantuária and her studio manager Andressa Rocha to discuss painting home, personal heroes and spiritual inspiration in more detail.

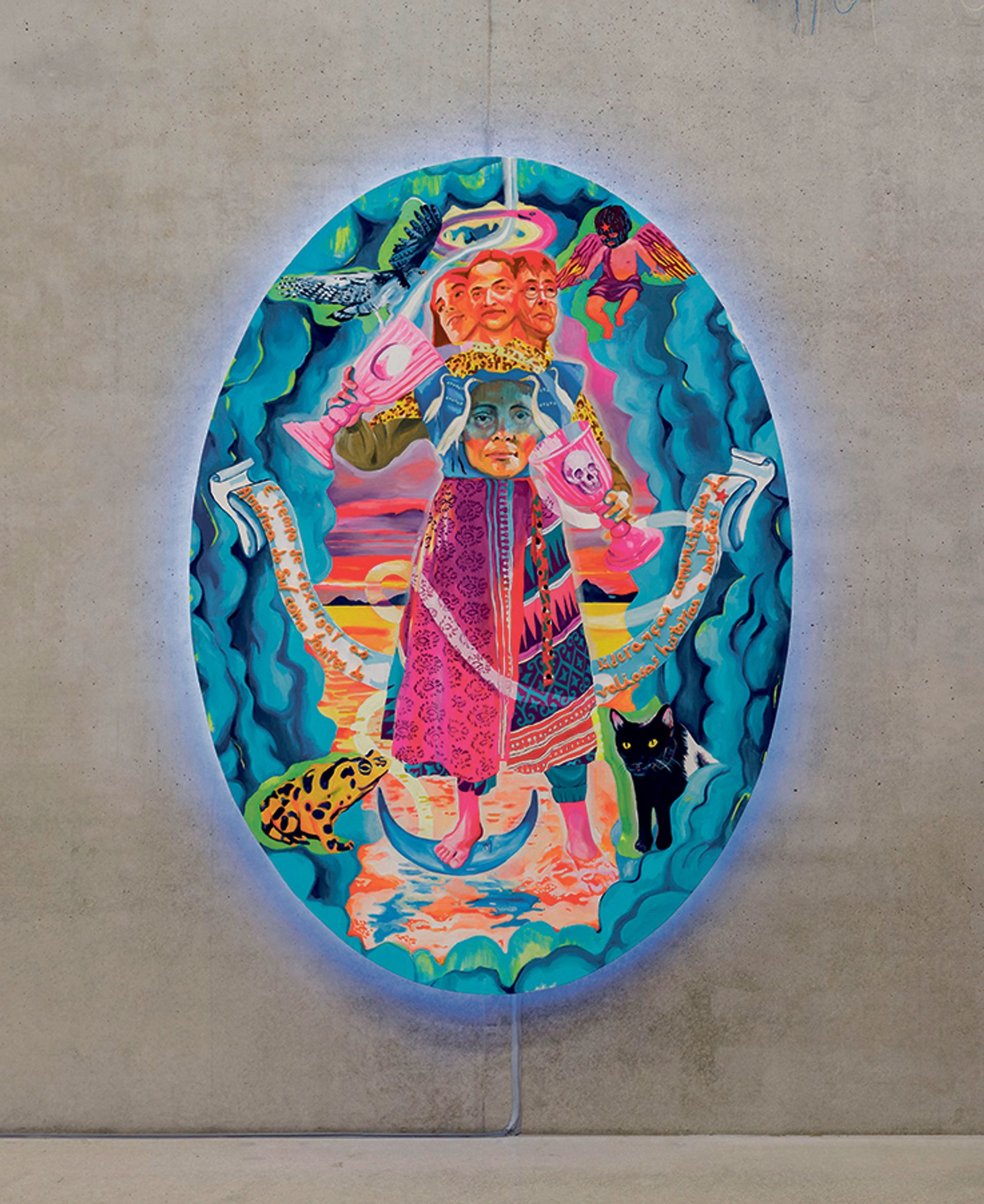

In The South American Dream, Cantuária incorporates spiritual, political and symbolic aspects Photo: © Oriol Tarridas; courtesy the artist and A Gentil Carioca, Rio de Janeiro

The Art Newspaper: How do you think your art interacts with the lives of the people you choose to paint?

Marcela Cantuária: In my interests and my research, I tend to choose people who are leaders from Brazil and the Global South, and combine this representation with my own magical perspective. Since I was a teenager, I’ve had this feeling for my class, and try to make the world make sense by re-enchanting it for myself politically with magic and fantasy.

Many of the people I choose to paint are those who have fought for Amazonia, because it’s been the most important forest and site in Brazil for the past 500 years. It’s still an urgent issue. I like to believe that when I represent these people, I do something spiritual, and try to honour them and their ideas in my heart. It’s not only political inspiration; it’s a gift for the spirits that I manage in my painting.

As this is your first show in a North American museum, did you expect any challenges trying to present these distinctly South American narratives to a foreign audience?

This exhibition, as well as the title, The South American Dream, was inspired by Miami: the people who live in Miami, the people who built Miami. It was inspiration that came from my South American point of view, and the responsibility that I felt came with representing a lot of different countries. It’s important to feel represented in the works, and when I research and compose my paintings I always look for new narratives and new people who are otherwise invisible in print and television. I want to show the ties between Indigenous fighters and their theories, and move past the stigma that they are otherwise portrayed with in the media. I thought the show in Miami could be something to enlighten a new audience to these people: not just activists from Brazil, but from Colombia, Argentina, Chile and Nicaragua.

Cantuária’s works focus on many of the women activists who have influenced her own life Photo: © Oriol Tarridas; courtesy the artist and A Gentil Carioca, Rio de Janeiro

Another challenge was to consider familiar standards, like painting colourfully, which Americans expect Latin American artists to embrace when they produce work. I wanted to use or avoid them in ways that break stereotypes, and instead promote a more diverse background, using the work to rewrite narratives and display women and activists hidden from history. It was a big challenge to work with the huge physical space of the gallery and figure out how the exhibition would achieve that.

The South American Dream is also meant to be something in contrast to the American Dream, something connected to our fights for the land and keeping our territory, about never having the desire to live in another place. It’s an idea of success that is not individual, and an understanding that the only way of achieving things is by working collectively.

I was also thinking about how it feels to go to a museum and spend a few minutes in front of a painting, thinking about how beautiful a portrait is. There are so many times you see a great painting but don’t know what it’s about, or why it’s of one woman and not another. My studio manager and I made a glossary of faces in my larger painting to address this, sharing the research, using bright colours to get people to pay attention and then enlightening them by giving the background of the women in the work. I want to make life from the painting, and make these people alive through the colours.

Your paintings often combine a wide range of references, from political posters to tarot iconography. How do you approach mixing these sources and picking the right one for a subject?

It has a lot to do with how I separate my compositions, thinking about the colour, the landscapes and the scales I paint people and their environments in. I have specific kinds of compositions depending on the subject I’m painting. Much of this is informed by my research on the history of women painters, female struggle and the magical aspect, which I like to bring into my work.

A temperança (the temperance, 2022–23), part of Cantuária’s show at Pérez Art Museum Miami Photo: © Oriol Tarridas; courtesy the artist and A Gentil Carioca, Rio de Janeiro

When I paint a woman I’ve researched, especially someone I’m inspired by, my composition develops in a certain way. The portrait has a main figure, who occupies the centre of the frame. Usually, in the background, I like to give hints to the details of the woman’s struggle and her contributions to the world. Symbols are important to me as well, and there are some, like stars, which I use to bring in a magical element and suggest a flourishing future, or a possibility of different realities. All of these elements are guided by the subject that I’m painting, and when I start a work, the composition comes after that choice.

• Marcela Cantuária: The South American Dream, Pérez Art Museum Miami, until 28 July 2024