This visually satisfying book celebrates nature printing through an impressive collection assembled by the co-author and New York book dealer Matthew Zucker. Nature-printed volumes spanning the period 1733-1902 are thrown open to the viewer—some of their pages are reproduced actual size, while others are in close-up to show off their

illustrated content in captivating detail. It is a publication that thoroughly relishes its subject and stimulates an enjoyment of it.

First off, though—what is nature printing? It is essential to know, because browsing through this book, flicking from beautiful images to others yet more stunning, one can be excused for wondering. The skeletal leaves in sepia that fill pages, ferns in muted colours with curling tendrils and plants with their roots—all of which could be mistaken for pressed and dried herbarium specimens—are not the product of a conventional printing process.

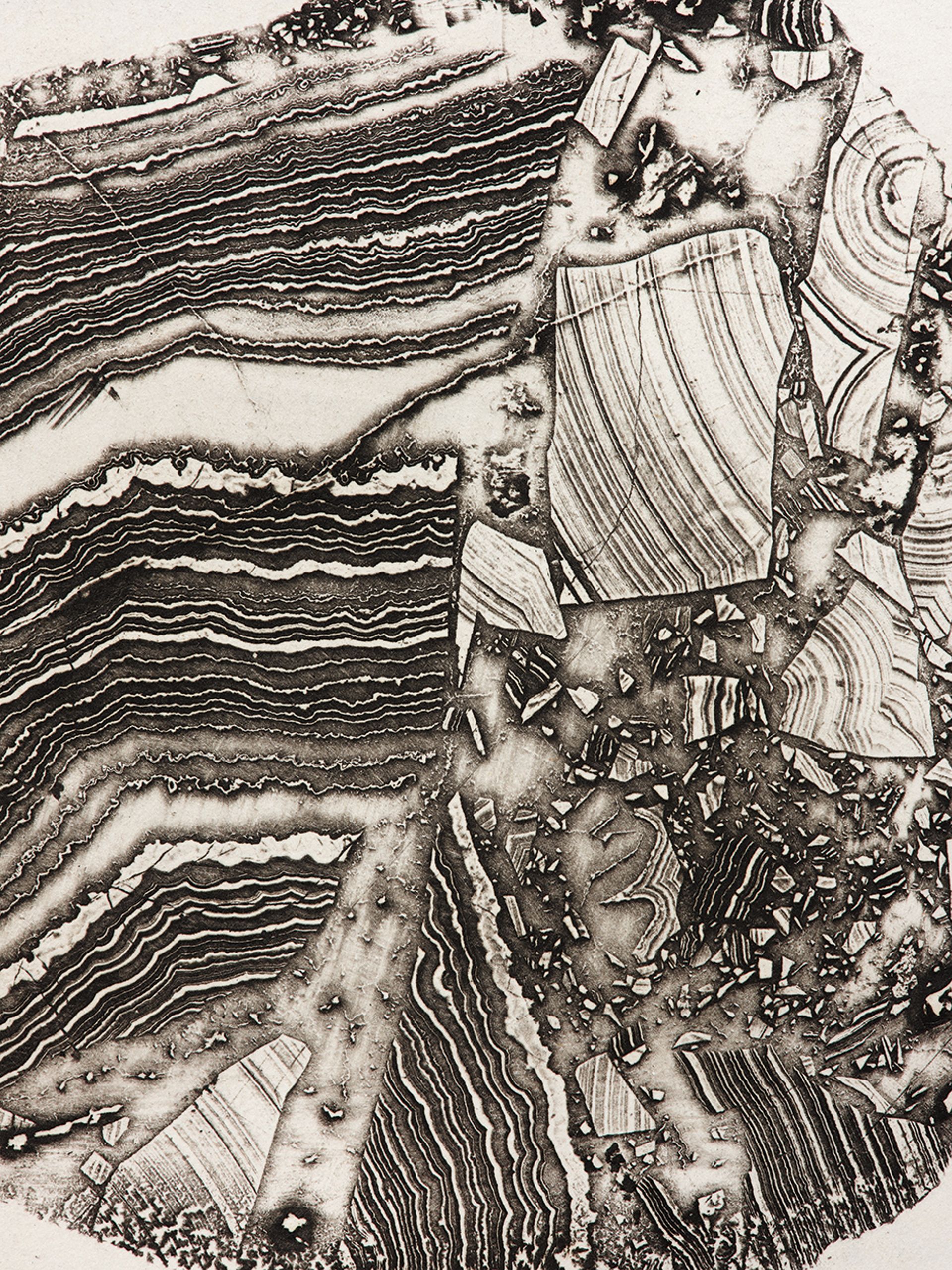

Nature printing is in fact the practice of printing directly or indirectly from the surface of the object itself. It is not only plants that can be treated in this way, but other natural objects too. In the book, alongside images of flowering plants, or grasses with their graceful blades and delicate inflorescences, are pages filled with the patterned surfaces of agates and meteorites, starfish, snake skins and even a bat.

Iimage by Franz Leydolt, who discovered a new method of depicting agates and other quartz-like minerals Vienna, Wilhelm Braumüller, 1851

Capturing Nature is about the history of nature printing and its different processes and techniques. At the centre of the book are sections that explain the 45 different printing methods identified from the books and journals in the Zucker collection. Locatable by their dark green pages, they sandwich a catalogue of the Zucker collection itself. The printing methods are divided between direct and indirect impression techniques. At its simplest, direct printing involves the inking of the surface of a natural object and pressing it onto paper, but also encompasses other processes such as the etching of sliced meteorites with acid to reveal their surface pattern, the “spatter” technique, and camera-less photographic cyanotypes.

Indirect techniques involve transferring impressions to a printing plate, block or lithographic stone. They include the several complex intaglio nature printing methods developed by Alois Auer (1813-69) and others, including Auer’s 1853 Naturselbstdruck (nature’s self-printing), a blanket term often applied today to all nature printing. Auer was the director of the prestigious Staatsdruckerei (state printing house) in Vienna, and likened his discovery—“how Nature itself furnishes a process of printing”—to the invention of writing and the Gutenberg press.

This information and more besides is contained in the book in much greater complexity and depth. As well as the technical explications of printing techniques, there are essays by botanical garden archivists, botanists and art historians covering everything from Benjamin Franklin’s contribution to nature printing, the connection between nature printing and photography, and Ernst Fischer’s 1933 essay Two Hundred Years of Nature Printing, which is reprinted in translation (“my work is probably the first publication on nature printing that can be considered reliable”, he claims at the end). Auer’s own explanation of his 1853 technique, which he published as The Discovery of the Natural Printing-Process, appears on p.192. All of this is rich material, but if one is to have a gripe, it is in the book’s design and structure. Blocks of illustrations placed at the front and back of the volume displace the contents page and index from their usual positions, making the book difficult to navigate. Locating and extracting information is not intuitive, which makes Pia Östlund’s explanation of the book’s structure essential reading (see p.47).

It is alarming to look at the image of the bat... thinking of the incredible compression required. Surely not?

The privileging of images is very far from a criticism as they are the book’s great strength, but how to identify and apply the different printing techniques described at the book’s centre to the beautiful images that populate the other pages is not obvious. Auer’s 1853 technique involved impressing the natural object into lead, then electroplating the impression to create a copper plate. It is alarming to look at the image of the bat, mentioned above, with this in mind, thinking of the incredible compression required. Surely not?

The book is not a comprehensive survey of nature printing. It is focused on the holdings of the Zucker collection, which begins in the 1730s and therefore omits earlier examples that stretch back to the Middle Ages. Its strength is in its illustration of works by Auer, Henry Bradbury, Constantin von Ettingshausen, Johann Hieronymus Kniphof and many more, when nature printing had evolved into a serious scientific process. On its back cover the book claims to be a gorgeous volume offering a visually stunning journey of printing method developments. It is certainly that, and a rewarding one too for those who can persevere with its structure.

• Matthew Zucker and Pia Östlund, Capturing Nature: 150 Years of Nature Printing, Abrams & Chronicle Books/Princeton Architectural Press, 360pp, $100/£75 (hb), published 25 April (US) 11 May (UK)

• Tabitha Barber is curator of British Art 1500-1750 at Tate. She is currently preparing an exhibition on historic women artists to be staged at Tate Britain in May 2024