Pope.L may not call himself one of the most influential performance artists working in the US today, but he has been known to pass out business cards declaring he is “the friendliest Black artist in America”. Known for his provocative and often absurdist works that deal with race, economic systems and language, the Chicago-based artist and educator works across multiple disciplines, from installations and film to painting and writing. His work is as distinctive as it is expansive. The hallmark of Pope.L’s practice is his use of iteration and intervention, both of which are evident in his Crawl series, which saw him move on hands and knees across large swaths of New York City on several occasions between 1978 and 2001. These performances were meant to counter “verticality”—a concept he uses to underscore the wealth and health it requires to be socially mobile. The gruelling physicality of the Crawls was only one aspect of them; equally important to the work was the reaction of onlookers, which could largely be summarised as compulsive avoidance.

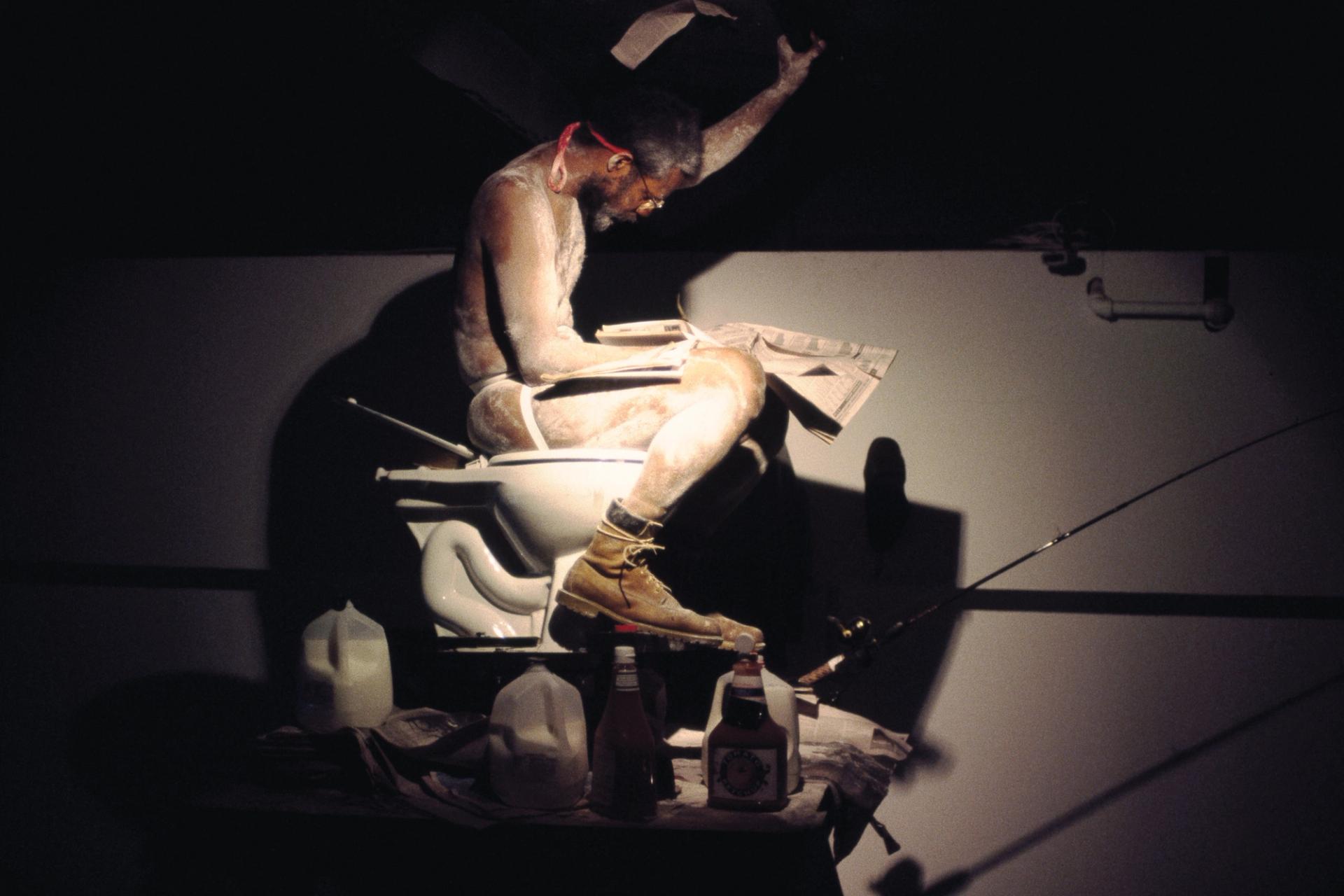

Eating the Wall Street Journal is maybe Pope.L’s most recognisable work, which has been performed in multiple different ways since 1991, when he first sat on an American flag and started eating pages of the Wall Street Journal, washing them down with milk and ketchup. It was a succinct commentary on the US’s glorification of capital and consumption, one made even more poignant when he restaged it at the Museum of Modern Art in 2000 while sitting atop a toilet and covering himself with flour to temporarily colour his skin white. A new version of this work is at the centre of an exhibition at the South London Gallery (SLG). For this iteration, Pope.L has removed the live performance element and, instead, three 4m-high wooden towers, topped with toilets and in various stages of collapse, will dominate the gallery’s main space. Around them, the Wall Street Journal issues will be stacked and milk jugs scattered; a flour-like substance will accumulate over the whole of the installation throughout the run of the show. The exhibition, which also includes previous film works like Small Cup (2008) and his Skin Set drawings from 2013, will be the artist’s first institutional solo show in the UK.

The Art Newspaper: Beginning with your Crawls, a lot of your performances have a certain shock factor and the element of public reaction is often fundamental to the work. Like the Crawls, Eating the Wall Street Journal has had numerous iterations since you first performed it. What was the public’s initial reaction to this piece?

Pope.L: In the beginning some people were perplexed. Some people were pissed off. Some, especially when I was doing the street version, ignored or avoided me.

Since the live performance aspect will not be part of the SLG installation, do you see the work changing in meaning again as it becomes a more sculptural, static experience?

The meaning of the new version will contain a palimpsest of the previous versions while staking out new meaning territory, but duration will still play a key role.

Why do so many of your works exist in several different versions?

Versioning is a way of creating incompleteness and ongoingness at the same time. The idea of a finished artwork is a fiction. The claim of “being done” is wishful thinking and a bit impatient.

Are you sitting comfortably? Pope.L performing his Eating the Wall Street Journal piece at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2000

Courtesy of the artist.

The film Small Cup, which features goats and chickens trampling over a seed-strewn and ruined architectural model resembling the US Capitol building, is an interesting piece in relation to Eating the Wall Street Journal. Both include the destruction and digestion of US institutions that function as symbols of power. What about the process of ingesting these symbolic items is crucial to the act of their destruction?

Both pieces bring the high/low via some sort of act of transformation. In both cases, gravity is also a collaborator. The use of animals and gravity make the pieces more impersonal, as if it is the most natural thing in the world for things like governments to fall apart.

A lot of your works, not least the two mentioned above, rely on US symbols or concepts. Do you think these works will resonate differently within a UK setting?

Probably. But I think the world of references I am working in is not so specifically narrowly American—in fact, some of the poetics of the works are derived from European romantic sources and their interest in death and decay, etc, etc. And, lest we forget, America was British before it was America.

At SLG, there is a recurring motif of accumulation, not only the flour-like substance that will coat the Eating the Wall Street Journal installation but also the marigold flowers that will pile up in the gallery’s Fire Station building. What is the significance of this accumulation overall? And why marigolds?

Marigolds reference the medicinal but also mourning, celebration and death. Accumulation speaks for itself.

Your shelf works often feature a combination of objects that have relevance to the place in which they are displayed. From where do you source the objects included in these installations and what connotations do they have for you?

I started making shelf works in the 1990s. The content for most of those works was organic materials such as onions or potatoes, or more processed goods such as cheap drinking alcohol and children’s things. The bottles I am using in the SLG show are UK products, either Buckfast or Cactus Jack drinking alcohol. Both of these products (Buckfast the older, Cactus Jack the contemporary) are marketed to young people (or the child in the adult) as an inexpensive means for altering one’s consciousness.

Pope.L's Litany often features objects connected to the location of the show; in London, it will include bottles of Buckfast and Cactus Jack

Courtesy of the artist

Let’s take a step back and look at your practice as a whole, rather than specific works. What initially drew you to performance?

I was drawn to it because it required the juggling of several crafts and techniques at once. In addition, the witnessing of the work was more direct and participatory yet temporary.

You also work in film, writing, painting, sculpture and other media. How do these various forms of expression speak to each other? Is there a specific type of media you often return to?

Each speaks in its own way to a particular use and context but some key media that I return to again and again are gravity, organic materials (including the human body), time and language.

In your artist’s book Hole Theory (2002), you offer some insight into your wide-ranging practice, noting that the lack of something is an ongoing concern. In it you write: “I do not picture the hole, I am the hole.” This hole has the power to generate other holes, material or immaterial, full or empty: “a voodoo of nothingness”, as you call it. This seems rather nihilistic. What is the role nihilism plays in your work? And what is its relationship to the absurdism that also permeates many of your performances?

Meaning is important. Just because I value nothingness or incompleteness or absence does not mean I do not value meaning. It’s just that sometimes meaning, our use of it, can be used to obscure meaning or devalue it. And then there is the obvious: as a tool, meaning has its limits.

What can absurdity offer as a tool of resistance and liberation? Are not recent political figures (both in the US and the UK) also often branded as absurd, and how might absurdity now be a facet of fascism rather than liberation?

The final word of James Joyces’s Ulysses is “yes”. The last words of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is “They do not move”.

• Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November-11 February 2024