It's been three months since the final whistle was blown to mark the end of the Fifa Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand—with Spain defeating the England team 1-0 on 20 August at Stadium Australia in Sydney. Now, the Fifa Museum in Zurich has unveiled some of the 400 pieces of memorabilia it acquired at the tournament for the museum’s collection.

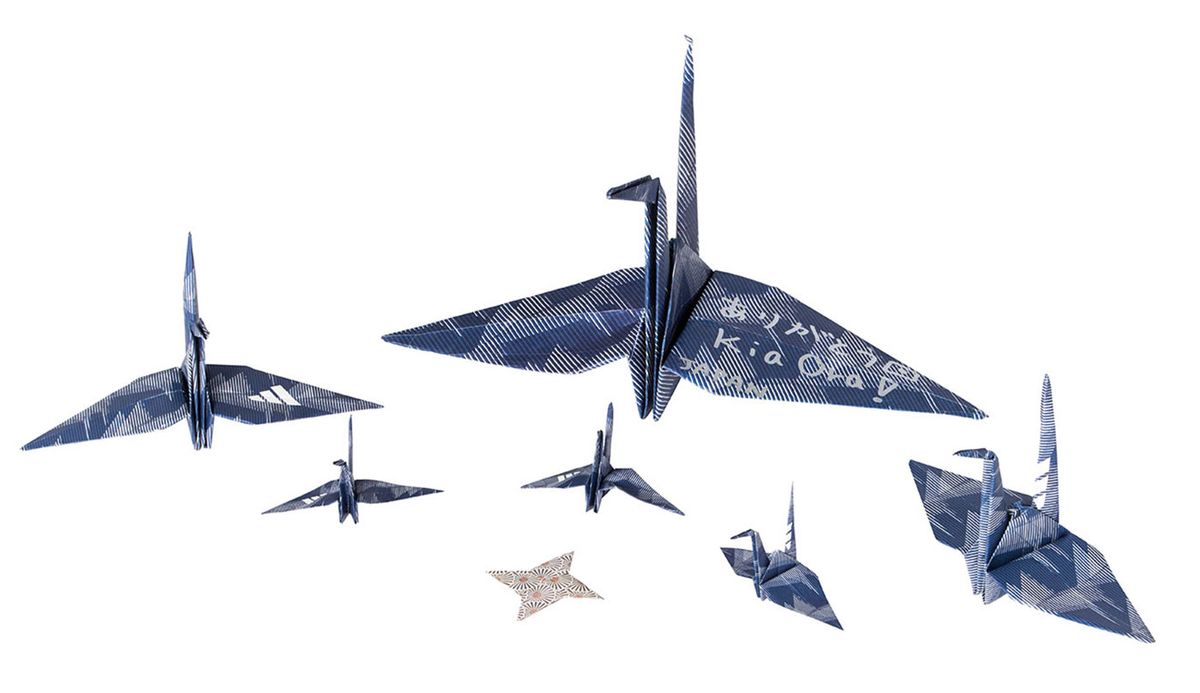

The works are part of a display that will be on show at the museum from 21 November. Among the most remarkable exhibits are symbols of welcome used to honour the Indigenous people of Australia and New Zealand, presented at the beginning of each match, and the orizuru folded crane paper sculptures—some of them nearly a metre long— left in tournament changing-rooms as a gesture of thanks by the Japanese team.

The acknowledgement of Indigenous community was one of the standout features of the tournamentMichael Schmalholz, librarian and archivist, Fifa Museum

Michael Schmalholz, librarian, archivist, and team leader for heritage at the Fifa (Federation Internationale de Football Association) Museum, headed a heritage team at the tournament that sent two of its members to each match to decide what souvenirs would be most useful to the museum's collection. Schmalholz tells The Art Newspaper that they asked as usual to be given shirts, boots, footballs, and pennants to mark significant moments in the tournament. The objects they received included the boots worn by Barbra Banda of Zambia when she scored the 1,000th goal in the tournament’s 32-year history in a match against Costa Rica. But they also, Schmalholz says, wanted to tell the 2023 World Cup's history on a deeper level.

The boots worn by Barbra Banda of Zambia when she scored the 1,000th goal in the 32-year history of the Women's World Cup in a match against Costa Rica. The Fifa Museum's heritage team has conserved the mud and grass on the boots, as the team feels that cleaning items used in live matches would rob them of their authenticity Courtesy Fifa Museum

The atmosphere at the tournament, Schmalholz says, was exceptional, with England's semi-final victory over Australia becoming the most watched programme in Australian broadcast history. To capture that tournament savour, the museum's heritage team collected objects from the ceremonies held before each game to acknowledge the Indigenous people of the two host countries as keepers of the land and to recognise their “unique stories and cultures”. That, he said, was “very important for us… the acknowledgement of Indigenous community was one of the standout features of the tournament.”

One of the ceremonial souvenirs is an A4 laminated sheet distributed in the stadium explaining more about the ceremonies. Another is a traditional poi, a “rope and ball” used and developed by the Indigenous Maori population of New Zealand. Poi performances involve the objects being swung in rhythmical and geometric patterns, thrown and caught, and used as a percussion instrument. They are often used as a means of storytelling.

A copy of the Binational Acknowledgement from Fifa Women’s World Cup 2023 (left), presented at the beginning of each game to acknowledge ownership of the land by Indigenous groups in Australia and New Zealand; and a poi, a traditional Maori rope and ball used in the story-telling performance art of the same name Courtesy Fifa Museum

The Japan team’s orizuru origami pieces acted as “a thank you message to the hosts”, Schmalholz says. They are folded from paper bearing the same orizuru graphic design, symbolising good health and good fortune, as is featured on the Japanese team’s blue home strip.

Industrial fans and data sets

The heritage team at the Fifa museum started planning months in advance of the tournament, studying squad lists to find players on the verge of reaching an important landmark in their World Cup careers or with a personal story that transcends the sport and the tournament. A piece that met all such requirements was the shirt worn by Linda Caicedo of Colombia, who scored in a win against the German team on 30 July. She thus became, Schmalholz says, “the first player to score in three different World Cups within one year: the under-17, the under-20 and the senior Women’s World Cup".

It was “like Christmas”, Schmalholz says, on the day the curators in Zurich received the boxes full of memorabilia. Banda's 1,000th-goal boots were taken out of their box with “huge lumps of grass sticking [out] between the studs”. Care was taken to leave the grass undisturbed. Meanwhile, the match-worn shirts were turned inside out and hung up, to be aired for two to three weeks with industrial fans in order to remove the smell of sweat. But the stains from playing and sliding around the pitch were left undisturbed. No piece of kit is washed or cleaned as that, Schmalholz says, “would destroy the historical authenticity”.

The jersey worn by Ella Toone, who scored for England when they defeated Australia in the semi-final of the World Cup in Sydney, Australia Courtesy Fifa Museum

Schmalholz's heritage team look after the museum's archive, library and objects. There is a separate photograph collection housing 130,000 physical pictures and many more digital, while film and television footage is collected and mined by Fifa Films. The museum has 8,500 objects and is lucky, he says, because it was “born digital”, database and all, when it was opened in February 2016.

Once the objects from the 2023 World Cup had been examined and aired they were photographed and given a unique inventory identifier and a full data set. “Without the data set, in the management database,” Schmalholz says, “the object might as well not exist.”

The museum is also home, for the next three months, to a larger version (drawing on Fifa's own collection) of Designing the Beautiful Game, an exhibition that opened at the Design Museum in London last year, and is rich in posters, architectural plans and models, banners and photography. It is the first exhibition, Tim Marlow, director and chief executive of the Design Museum, said in 2022, “to look at the game of football through the lens of design”.

- 2023 Women’s World Cup Showcase, Fifa Museum, Zurich, from 21 November

- Designing the Beautiful Game, Fifa Museum, Zurich, until 24 February 2024