Marina Abramović may be one of the only people who could turn an opera into an endurance test. Not just for herself (the 76-year-old performance artist spends an hour of the 90-minute performance lying motionless in a bed) but for the audience also.

7 Deaths of Maria Callas strips down the operatic form to seven arias, each taken from a different work and performed in succession. Indeed, without the drama, the production occasionally gets stuck in staccato.

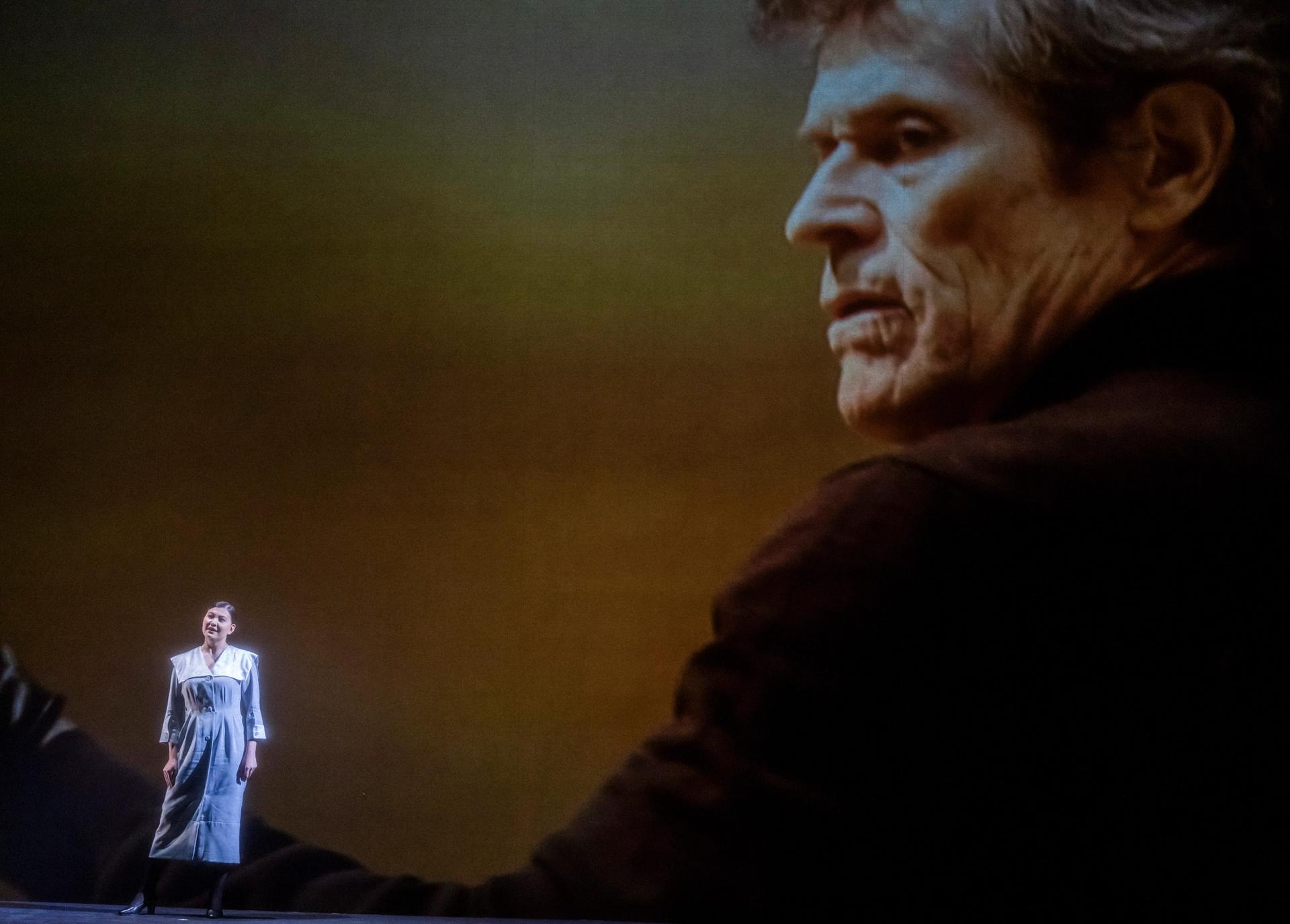

However, strong performances from the selected sopranos and the vitality of the other elements on stage: seven short films featuring Abramović and the actor Willem Dafoe, the narrative elements of Petter Skavlan and Abramović’s libretto and strong sound design from Luka Kozlovacki help give 7 Deaths a sense of cohesiveness.

The jumping point for this work is Abramović’s first encounter with Callas—listening to the radio, aged 14, in Yugoslavia. But the project has little to do with Callas’s biography and more to do with what she represents to the artist: a woman who embodied heartbreak and death on several stages over many years and who eventually came to embody it in her own life.

If this is sounds somewhat like projection on the part of the artist (and a lot like the heavily stylised myth Callas scholars have been working against; did she actually die of a broken heart?), that's because it most likely is. Abramović interweaves her own experiences with Callas’s. Namely the breakdown of her relationship with her partner and fellow artist Ulay, which in 2010 reached the public arena during Abramović’s exhibition The Artist is Present at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. As such, at the London Colloseum, two divas find themselves competing for the stage.

Nadine Benjamin and Marina Abramović in 7 Deaths of Maria Callas © Tristram Kenton

7 Deaths is most adept, with its laser-focus on the demise of its heroines, at defamiliarising the endings of some of opera’s most well-known works. Those in search of a plot instead find a comment on the use of a recurring motif: the damnation of women on the operatic stage.

Here, the project functions like an essay on the operatic form. Much like an opera-going audience, 7 deaths is omniscient; it knows what genre is being staged and it knows how the story ends. However, it does not accept the gory deaths of women as simply a generic feature. Audiences will find ideas about fate, misogyny as well as the patriarchy embedded in heterosexual romance floating around. However, in the loosely drawn narrative of the production, the specifics of the critique often gets lost.

The Art Newspaper: How did you decide which seven arias would go into the production?

Marina Abramović: I was thinking about dying and how [in Maria Callas’s repertoire] women die mostly for love. And how in that way, they are killed by men. From there, I found the most appropriate arias. La Traviata—where Violetta sacrifices her life in her love [for Alfredo]. Tosca—where she jumps upon discovering her lover is dead.

And then there was Madame Butterfly, which was particularly interesting because I couldn’t just do hara-kiri in the 21st century. I was thinking—even before Covid—how our world is going to be totally radioactive and toxic [in the future] and so I had Cio-Cio San take off the hazmat suit and expose herself.

And then there’s Norma’s Casta Diva, which was the first one I decided on. This piece was the first time I heard Maria Callas back when I was 14. In it, Norma betrays her people and her country for her love and then is betrayed by him. She decides to burn in the fire as punishment but it’s also the only one where the man is burned too. In a way to me, she’s the hero and he was just the coward.

So, [my selection is based] on all these different ways of thinking about death: the knifing, the madness, the radiation but also choosing Callas’s most romantic roles. She’s very well-known for Médée but that story is about the death of her children—and while she kills because of love that was not the story I wanted to portray.

Karah Son and Marina Abramović in 7 Deaths of Maria Callas © Tristram Kenton

Did you ever feel constrained by the decision to tell the story with only arias?

It was so difficult and complicated: how we can not only tell her story but put my story into her story. Because I also experienced a broken heart—only my work saved me and hers did not, and I was thinking: “how could I mingle this together?”.

But also, I’m a performance artist—so in the Otello [film], it’s not just Otello choking Desdemona, I use the snakes which I use in my work Dragon Heads and several other performances.

But how could I tell the story between the arias? So, then I came up with the idea of the clouds. I’ve been painting clouds since I was 17 or 18 but here, I asked [the Italian artist and film director] Marco Brambilla to make the digital clouds which are projected on the big screen. The idea was every set of clouds [in between the arias] represented a different mood and introduced the next killing; you have morning clouds, the full moon, the fiery sky, a tornado.

And then with the clouds, in a very abstract way, is my voice telling the story—but not explaining. In the beginning—I have to tell you the truth—we were really thinking of telling the story of every opera but that was so reductive and so stupid, I didn’t like it. Because you realise that an opera going audience knows all the stories—however, a lot of my audience is young and have never been to the opera in their lives. So, you take the middle way: I’m talking about the ideals without telling the story.

And then you have the film which helps to explain things—and my hope is that if this successful, the young audience will go out and find these stories out for themselves.

Aigul Akhmetshina and Willem Dafoe in 7 Deaths of Maria Callas © Tristram Kenton

The staging of the first part of the performance feels Surrealist: you are laying there under a strange luminescence—distinct from the rest of the stage, the soprano on the opposite side of the stage to you, the film screen creating a very strong line behind you all.

One is reminded of Giorgio de Chirico as well as Rene Magritte’s night paintings but what were your influences here?

Well, you forget one part which is the screen where the clouds are being projected—that adds another layer. I just knew I wanted to create a very modern set. And I also knew I wanted to add a performance element—so you have me lying in the bed in real-time for an hour. If there’s one thing I’m good at, it’s being motionless—it’s kind of my thing.

But it was really important to combine so many things. We have the performance, we have the video, we have the acting, we have the opera singers, we have the orchestra, and the projections behind—especially the one with the with me and Willem—it's important that it's not just a mega background. For example, [in the Otello film] you see the snake almost come to my own bed when I'm lying there, so you have this feeling that you're in the screen.

But I wasn’t really thinking about painting. I just knew I wanted to combine different art forms—especially because I’ve never done opera in my life. If someone had told me even ten years ago, I’d be doing opera I wouldn’t even have believed them because it’s such an old form of art.

In London, the English National Opera is known for staging more contemporary, experimental works. Did that play a role in choosing the venue?

Well, in 2020 when we started working on this opera in Munich, I was so interested in having it at the Royal Opera House because of Callas’s performance history there. So, I went there three times and three times I got refused.

And then because I never give up on anything, I invited the English National Opera associate artistic director [Bob Holland] to see the show in Naples in the Teatro di San Carlo. The performance got a ten-minute standing ovation. After the show he came to my dressing room and said, “I think we’re going to have this show in London”.

It’s been one of the best experiences of my life—the kind of love, support and understanding. I don’t know if you noticed but I asked all the crew to come onto the stage at the end; I wanted people to understand how much energy goes into this, you can’t do this yourself. I think in my blood, I’m a real communist.

One of the critiques of the project is that Maria Callas isn’t really invoked in this project about her life until the very last moment.

Do you believe that you succeeded in bringing Callas’s presence onto the stage?

It was definitely my intention to bring her onto the stage, but it was very complex. How do I keep this fine line between myself and her.

So, for example, in the last scene we went for an absolute replica of the bedroom where she died with her bedsheets, flowers, the sleeping pills next to the telephone. But the photographs that surround her are my own photographs: my wedding, my own broken heart, not hers.

But bringing back Callas is impossible—it’s her voice that will never die.

There was an attempt a few years ago at this venue to bring Callas back to life in the form of a hologram but it didn’t work, it could not replace her. I never wanted to replace her; this is why in the end the voice comes from the gramophone, but it cuts off before the end of the aria. Because the aria has to finish in your head, it has to finish in your memory of her because her voice is irreplaceable.

Marina Abramović in 7 Deaths of Maria Callas © Tristram Kenton

Is 7 Death of Maria Callas a critique of opera?

It’s a critique of the trope where the woman always dies. Why always women? But I think women are so much more beautiful than men, their death is more dramatic. You’re more moved emotionally—men just go and die and that’s it.

But look at the literature, look at the cinema, look at the theatre: we’re always more emotionally involved when women die at the end. It’s also a comment on the way women die, not just in opera—a man betrays a woman, it doesn’t necessarily lead to suicide, but the woman betrays the man and immediately dies. It’s almost a curse.

There are some elements of 7 Deaths that draw from your practice: the focus on the body, blood, the endurance tests. Where do you see it fitting into your body of work?

When I was starting my career as an artist, I had so many different ideas that weren’t in a line with each other—it really looked all over the place.

I knew I had an incredible need to do them without having the exact knowledge why. As the years go, I have the wisdom to put the puzzle together. I don’t have this wisdom yet with this opera but I’m sure the moment will come when I understand where it fits. I only have this intuition; this urge to do things.

But I do know it has something to do with ageing. I’m 77 this year and I can’t do certain performances from when I was 20, it’s just not possible. But this opera I could easily do until I’m 103.