Readers of this column will be familiar with its coverage of the plethora of environmentally-themed shows recently popping up in museums and galleries worldwide. A few have made valuable contributions to changing attitudes and promoting action, but many others tend to be stuck in preachy mantras that either bemoan our lost links with the natural world or berate humankind for the multiple ways in which it is trashing the planet—or, of course, both.

Thankfully, RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology at the Barbican Gallery goes beyond hand wringing and finger wagging to deliver important messages about how we need to view and act upon the current crisis. The work can be viewed through the lens of ‘ecofeminism’, a school of thought that links gender oppression with humanity’s destruction of nature. RE/SISTERS brings together 250 works by around 50 artists from the 1960s to the present day to demonstrate the ways struggle for gender and environmental justice have long gone hand in hand and how they continue to do so.

It’s a sprawling, complicated show but also a timely, important and hard-hitting one, full of great work that takes no prisoners. Throughout we see how RE/SISTERS worldwide—whether from indigenous societies, communities of women or gender nonconforming people—have all played a crucial role in ecological activism, making work that responds to these intersectional abuses, and using art to protest and fight back.

In the first section devoted to the brutal exploitation of natural recourses and the ravaging of landscapes, Simryn Gill’s horribly beautiful photographs bear witness to the open pit mines that lacerate the landscape of Western Australia as well as the tatters of waterborne plastic festooning a Malaysian mangrove forest. Other powerful statements include Sim Chi Yin’s photographic installation documenting the building of luxury islands in Singapore and China and the devastation to local housing along the Mekong River caused by the massive extraction of sand for these high end building projects. We also see Taloi Havini’s three channel film which follows Agata, an indigenous matriarch in Papua New Guinea, as she stoically goes about her daily life sifting gravel in the shadow of a copper pit that has turned her surroundings into a toxically stained desert. In the oil-dependent countries surrounding the Caspian Sea, Chloe Dewe Mathews focuses on these diverse regional cultures and their intimate reliance on these extractive economies that also threaten to destroy their surroundings. Striking examples include a woman bathing in crude oil in Central Azerbaijan and a noxious gas-emitting crater in Turkmenstan still ablaze since it was caused by Soviet drilling in 1971, known locally as the ‘Door to Hell.’

In myriad ways RE/SISTERS confirms the essential role of women in the fight for climate justice, ecological rights and in opposing capitalism, extraction and exploitation. A stirring section on female-led environmental protests spans from the environmental pioneer Agnes Denes planting 8000 square metres of wheat on the prime real estate at Battery Park landfill in New York City in 1982 to Susan Schuppli’s 2022 film highlighting the demands by Inuit activists for the legal right of ice to remain cold.

Especially striking are the recently discovered photographs of 1980s Greenham Common activism in the UK taken by the woman-only Format Photographers. The photographs depict women in the Greenham peace camp using artworks, zines, flyers, collective singing and webs of wool to communicate their feminist message for peace and to protest against militarism and patriarchy with compassion and humour. These good natured, visually and symbolically potent strategies were then emulated in the US by the Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice set up at the Seneca Army depot in upstate New York in 1983, and recorded in a series of vivid colour photographs taken by Joan E Biren (JEB).

Tree hugging looses its sneery pejorative connotations in Pamela Singh’s moving images of the 1990s protests of the Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas who successfully used their bodies as human shields against rampant deforestation by state and industry-sanctioned loggers. More recent examples of active resistance include Poulomi Basu’s remarkable series Centralia (2010–20), which captures the key part played by female fighters in the indigenous Adivasi people’s militant struggle for land sovereignty against the Indian government, while in Flint is Family (2016–20), LaToya Ruby Frazier’s intimate photo essay connects water contamination with systemic racism in the recent scandal in Flint, Michigan.

Judy Chicago's Immolation from Women and Smoke (1972)

Fireworks performance, performed by Faith Wilding in the California Desert

© Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society(ARS), New York; Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives; Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco

RE/SISTERS also includes many of the female artists whose work draws links between their bodies and nature, and who also often make connections between gender and water, and feminism and access to the land. These bodily investigations encompass the historical and the contemporary, whether Ana Mendieta’s blending of ancient ritual with performance art by plastering herself in mud and blending into the landscape; Judy Chicago filling the Californian desert with clouds of coloured smoke, or Francesca Woodman’s ghostly mergings with trees. In her Nature Self-Portrait series of the mid-1990’s Laura Aguilar inserts her own large bodied, working-class queer Chicana naked presence into the heroic rocky much (male) mythologised desert of the American Midwest, mocking but also reappropriating its dramatic forms by combining them with her own.

As Aguilar demonstrates, for many RE/SISTER artists, locating the female body as part of the natural world isn’t just lyrical—it's hardcore political. Tee A Corinne slyly transforms the Oregon countryside into a subversively eroticised landscape by seamlessly blending fleshy vulvas with the textures of tree trunks, rocks and clouds while Xaviera Simmons plays with and offa checklist of historic racial stereotypes concerning the subjugated Black American female body in her photographic self portrait where she sits on a throne-like wicker chair, surrounded by towering reeds, further parodying racial caricaturing with her naked body covered in black paint and bright red accentuated lips.

Humour and playfulness also show themselves to be key strategies of resistance and survival.

The painted breasts and bellies of the UK based Neo Naturists performance art group may obliquely evoke ancient Goddess rites but their exuberant deliberately under-rehearsed spontaneous actions also grapple with lazy associations of the feminine with nature to explore wider aspects of gender and identity and body positivity with riotous humour. In the same teasingly critical spirit Feminist Land Art Retreat’s 2017 Heavy Flow, a film which features volcanoes spewing lava accompanied by a soundtrack of self-help style advice on how to create a successful self portrait, mocks the grandiose masculine traditions of land art and also provocatively counters the epic ejaculatory connotations of the film’s volcanic eruptions by relating their lava to the flow of menstrual blood.

Lest there be any doubt that the debate has decisively moved on from old-school binary definitions of women as nature (irrational, unstable, subjective, volatile mother earths), opposed to men as culture (rational, reliable, objective, proactive pillars of strength); RE/SISTERS opens with the clarion call of Barbara Kruger’s trenchant photopiece which depicts a prone woman with leaves over her eyes and bears the caption ‘We Won’t Play Nature to Your Culture.’ Instead, what this landmark exhibition underlines is that, whatever our location or gender preference, we are all both nature and culture, and we ignore the mindset and strategies of these ecofeminist RE/SISTERS at our peril.

Joseph Mallord William Turner's The Lake, Petworth, Sunset; Sample Study (c.1827-8)

Tate Collection

The irreverent but powerful activism of both The Neo Naturists and the women of Greenham Common also feature in Radical Landscapes: Art inspired by the land, at the William Morris Museum in East London. This exhibition includes work from across two centuries and takes a more historical standpoint to explore the rural landscapes of Britain as a space for political and cultural protest as well as environmental action and artistic inspiration.

Radical Landscapes had an earlier more extensive incarnation at Tate Liverpool in 2022 and like RE/SISTERS it confirms that it is impossible—indeed disingenuous and dangerous—to take a neutral view of the natural world, especially today. Seen through the prism of William Morris, the 19th century socialist activist, environmentalist and founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement, in whose house the exhibition is staged, Radical Landscapes reflects on how British landscapes have been read, accessed and used across social, class and racial lines as well as within the current global climate emergency.

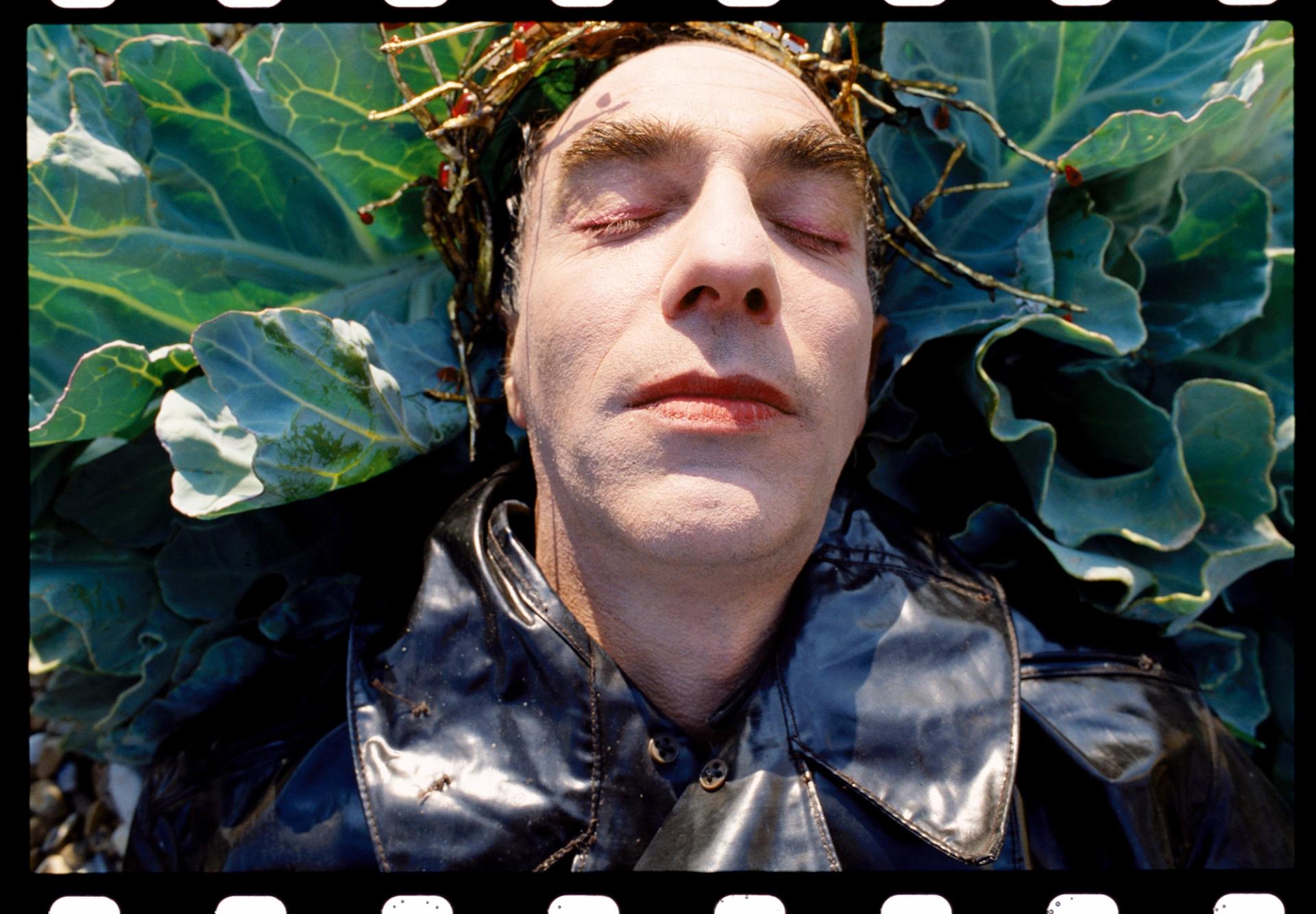

Still from Derek Jarman's The Garden (1990)

Courtesy & © Basilisk Communications

Each work presents landscapes and natural forms freighted with hidden stories and agendas. Whether in John Constable’s paintings of a seemingly idyllic 19th century Suffolk which was in fact an early UK centre for industrial scale agri-business; or Derek Jarman’s vivid and elegiac 1990 film The Garden made in the shadow of Dungeness nuclear power station and against the backdrop of his own battle with HIV, or Jeremy Deller’s 2019 sign, (A 303) Built by Immigrants, which refers to the revelation that the trunk road that runs past Stonehenge was built by the descendants of Neolithic migrants who came to the area from present-day Turkey around 6000 years ago. Each instance is a reminder to carefully consider how we approach the land and to follow the early stance of William Morris in striving to protect and sustain it.

As both these thoughtful and inspiring shows confirm, there can be no distinction between environmental and social justice. If we are to have a future we have to strive for an equitable society in which people—all people—and planet alike are considered, respected and treated fairly. We are all in this together.

• RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology, Barbican Art Gallery, London, until 14 January 2024

• Radical Landscapes: Art inspired by the land, William Morris Gallery, London, until 18 February 2024