How do you measure the success of an 'art week'? This was the question hovering over the vibrant third edition of Art Week Tokyo (AWT), which took place 2-5 November in balmy sunshine. City art weekends, art weeks and international fairs are now an integral part of the crowded art world calendar; many collectors and curators had hot-footed it from Art Collaboration Kyoto (until 28 November) to visit AWT's 50 participating galleries and museums. As in previous Tokyo editions, free shuttle buses for VIPs and public alike facilitated the hopping between small commercial galleries (with clusters, for instance, in the Roppongi district) and established art institutions, with watering-holes like the specially commissioned AWT Bar along the way.

Revealing the depth and creativity of Tokyo's contemporary art scene is one of AWT's overarching objectives, and the spotlight this year fell on 64 artists who have shaped its expression from post-war to today. Veterans like Nobuya Hitsuda (b 1941), a legendary teacher as well as painter of seemingly bare, neglected landscapes, were featured (Kayokoyuki gallery), alongside younger artists like Saori Miyake, whose uses AI-generated images to aid her lyrical reflections on the fragility of nature (Waiting Room gallery). Prices overall are still remarkably reasonable and, combined with the low value of the yen, there were many bargains to be had, especially in the $2,000 to $5,000 dollar bracket.

Saori Miyake's Still from Nowhere in Blue (2023) Single channel video.

Courtesy of the artist and Waitingroom

Generating sales is, of course, one major goal of the exercise. New to the party this year was a curated sales platform, AWT Focus, designed not only to facilitate purchases from contributing galleries but also to educate visiting international clientele and inspire a new generation of Japanese collectors. Guest curated by Kenjiro Hosaka, director of the Shiga Museum of Art, Otsu, the debut show was installed over the three floors of the private Okura Museum of Art, located within the grounds of AWT's partner hotel The Okura Tokyo.

Showcasing 100 works by Japanese or Japanese-based artists under the theme of Worlds in Balance: Art in Japan from the Post-war to the Present, the museum show provided a central axis and grounding for many visitors. For Hosaka, one of his curatorial objectives was "to use the format of the sales platform to explore the possibilities for a new mode of curation at a time of increasing privatisation, on the one hand, and the rise of artist-curators and collectives, for whom exhibition-making is an extension of artistic practice".

Art Week Tokyo's Director and co-founder, Atsuko Ninagawa, explains that the week is driven by this dual purpose: to activate the market in Tokyo while still promoting a genuine art-focused, non-profit ethos (with talks and video programmes on the menu as well). Her gallery featured an emphatically dark show by British artist Derek Jarman, reflecting on another significant theme: Japan’s long history of productive international discourse and exchange.

Installation view of the inaugural AWT Focus, “Worlds in Balance: Art in Japan from the Postwar to the Present,” at the Okura Museum of Art, Tokyo, 2023

For Ninagawa, however, measuring AWT's success has become ever more challenging. How do you evaluate a non-profit art project that brings together so many stakeholders: from commercial galleries, institutions, and government [Tokyo Metropolitan Government and the Agency for Cultural Affairs]; from corporate partners and the multiple publics that the event hopes to serve; from fellow art professionals and collectors "all the way through to individuals who may be actively engaging with contemporary art for the very first time"? Most prominently, AWT is organised in collaboration with Art Basel (Ninagawa declines to comment on the price paid for this partnership), which brings it the expertise and the connections of the mega-fair brand. For Art Basel, AWT provides a key strategic convening point, particularly given the importance of its Hong Kong fair, and the potential for Japan to play an ever-increasing role in a sophisticated Asian art ecosystem.

"My team and I have done our best to take all these stakeholders into account in building up the structure of Art Week Tokyo" Ninagawa tells The Art Newspaper, "and I’m confident our event provides something of value to each of them. But different stakeholders have different measures of success. For the government, it’s about numbers. I don’t set the numbers myself, so I ask the government to give me the numbers beforehand [fortunately, she says, their expectations are very reasonable; last year's event attracted more than 32,000 visitors]. For Art Basel, it’s about delivering world-class quality. For museums, it’s about promotion and bringing people to their exhibitions [ the latter included the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo’s vast survey of David Hockney, the artist’s first large-scale exhibition in Japan in 27 years]. Raising the public profile of galleries is also important, but of course we want to stimulate sales, and that’s the most uncertain part, because it has to be done by the galleries themselves."

Art Basel's Vincenzo de Bellis, a year into his new directorial role overseeing the four Art Basel fairs and exhibitions platforms, agrees that the quality and diversity of AWT's offering is all important, but at the same time his organisation has set itself its own overarching objective: to guarantee that all Art Basel's collaborations "have their own soul" and provide space for new discoveries. Speaking to The Art Newspaper at the Okura Hotel, he explains that while Art Basel is a major global enterprise, "in the 2020s context has become very important, and to think only through a global lens doesn’t do justice to the specialities of every place". More and more, he says, "we and the public look for the unexpected, something that can only be found in a particular location".

De Bellis's initial task was to shape the leadership of Art Basel's four fairs (Switzerland, Hong Kong, Miami Beach, and Paris) so that each fair has its own vertical leaders, allowing for even more nuanced curatorial ideas and selections. "This", he says, " fits exactly with our art week philosophy too. The art week model has become very popular—S.E.A. Focus and Singapore Art Week, Berlin Art Week, Art Basel Cities Week in Buenos Aires—where we highlight the local area and create a moment besides the fairs". He describes Tokyo's AWT Focus show as "a great discovery" in terms of a new format, allowing Toyo's 'week' to combine strong city-wide gallery presentations with "A mini-Japanese art history course in one go; it is where the museum and the market blend". Vital to the realisation of this model, he acknowledges, was Japan's governmental support.

Such an AWT Focus-style innovation, he believes, will become more important with a generational shift in potential art collectors and the way that new technologies are used: "The more we can support understanding and learning beyond the 'most known things' the better," he says, "then we can help people to become more nuanced in their collecting habits. "I personally believe that we have an important responsibility to connect collecting habits and education." In AWT this process has begun in a private museum, and he sees no reason why it couldn't happen in a public museum too. The fact that everything is for sale—if something resonates you can contact the contributing gallery (there are no price tags)—he finds" discreet; elegant".

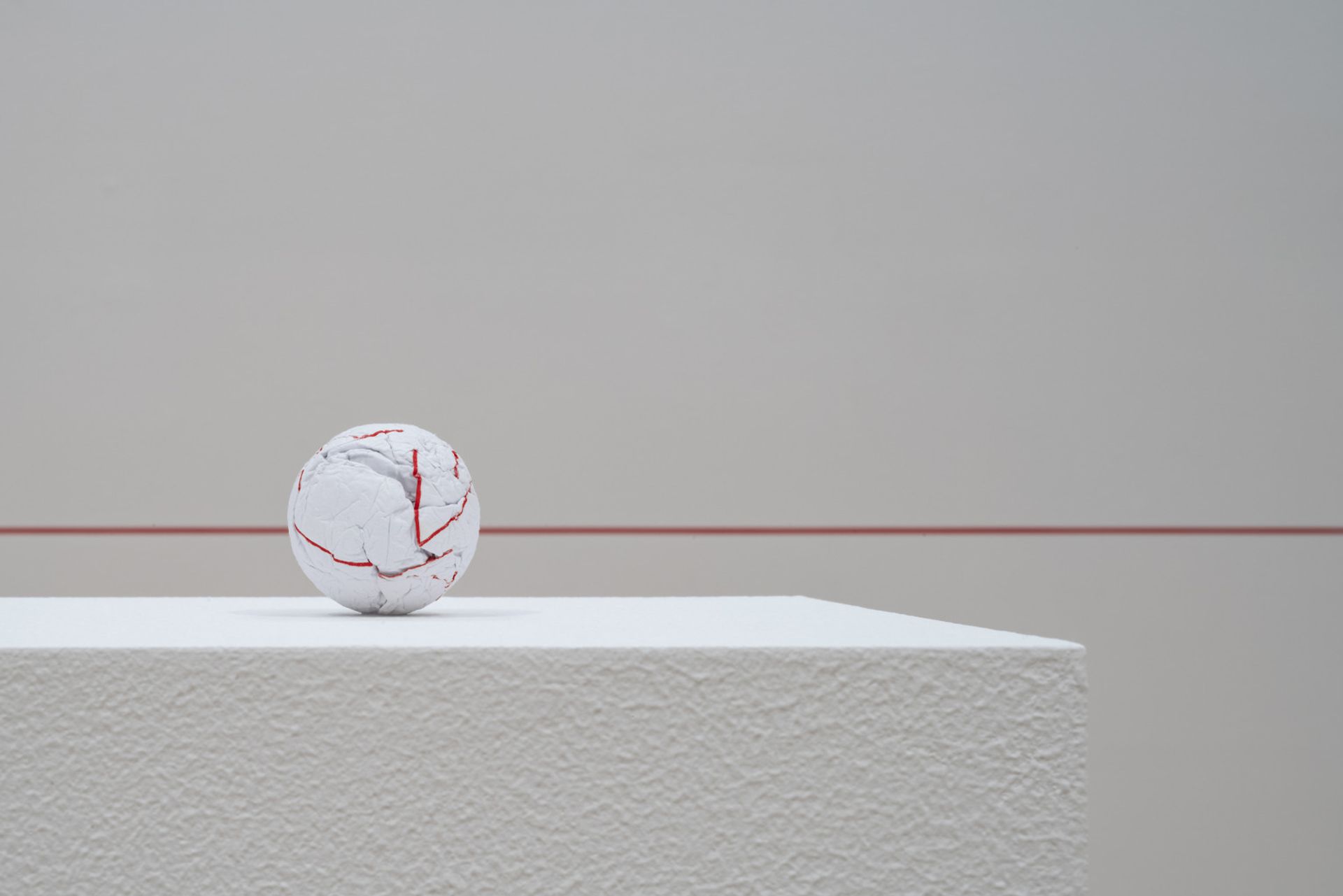

Yoko Terauchi's Pangaea Red Square Line, (2021). Installation

view, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, 2021

Photo by ToLoLo. Courtesy Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

For Art Basel, the ultimate success of AWT will be measured on a longer trajectory than one of its fairs. "We are looking for more Japanese collectors, and the growth of Japanese collectors moving internationally. We saw this strategy bear fruit at the last edition of Art Basel Hong Kong, with a more significant number of Japanese collectors, and visa versa, " he says. "And when Japanese galleries show at our fairs, like Nina's [Atsuko Ninagawa’s] we can see if there is traction over the medium to long-term." Cities with a strong fair presence, like London, he admits, might find it difficult to replicate the week/weekend model. "But the more organised we can all be, the better. Otherwise, we can stick with the same buyers, but the art world won't expand."

There are lots of other pluses to AWT's particular model too, says Ninagawa. "One of the under-appreciated elements of Art Week Tokyo is that we don’t charge any of the galleries a participation fee, which gives them more flexibility in planning their exhibitions. A lot of our visiting curators were thrilled to discover the mid-career artist Yoko Terauchi’s simple but profound paper installation at Hagiwara projects, and I’m hearing from my international clients that they are buying works from younger galleries, which is exactly what we want to happen."

Ninagawa also has a more personal measure of success, one that is underscored by her own experience of growing a gallery business. "Young gallerists now are under much more pressure to make money than I was when I was starting out 15 years ago, and that pressure can drive them to focus solely on saleability in building up their programs. I want to encourage them to keep doing what they believe in and to keep exploring the possibilities for art. So, through AWT we wanted to connect the established galleries with the younger galleries and have them share their resources and connections. If that enables even one gallery to keep going for another six months or so, by doing what they believe in doing, then I think that is a significant achievement."