Artists from Henri Matisse to Dieter Roth have relished conceiving and creating their own books, allowing them to meld techniques and styles across a variety of disciplines. An exhibition at the British Museum, Artists Making Books: Poetry to Politics (until 18 February 2024), and an accompanying publication shift the focus however to an extensive collection of artists’ books from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia. The exhibition curator Venetia Porter and author of the book says that the project “aims to expand the boundaries of the subject” by concentrating on 61 artists.

So why is this an important topic? “There is a ‘Western’ canon of books made by artists: the legacy of the livre d’artiste, the early 20th-century innovation that took place in Paris with wonderful books made by artists like Matisse, Joan Miró and others. However, up until now, the important collections, exhibitions and publications on this subject have tended not to go beyond what is a very Eurocentric approach to this topic,” Porter says.

In Porter’s view, artists’ books by Mena (Middle East and North Africa) and South Asian practitioners should be studied, exhibited and discussed alongside books by Western artists. “Unfortunately, art connected to these regions tends to be considered only in its own silo, which is one reason why I think the topic is important. The second is the books themselves and the nature of the subjects within them… complicated topics of Mena/South Asia history and politics [for instance] and the delicacy and subtlety in the way artists from all round these regions approach subjects literally from politics to poetry,” Porter says.

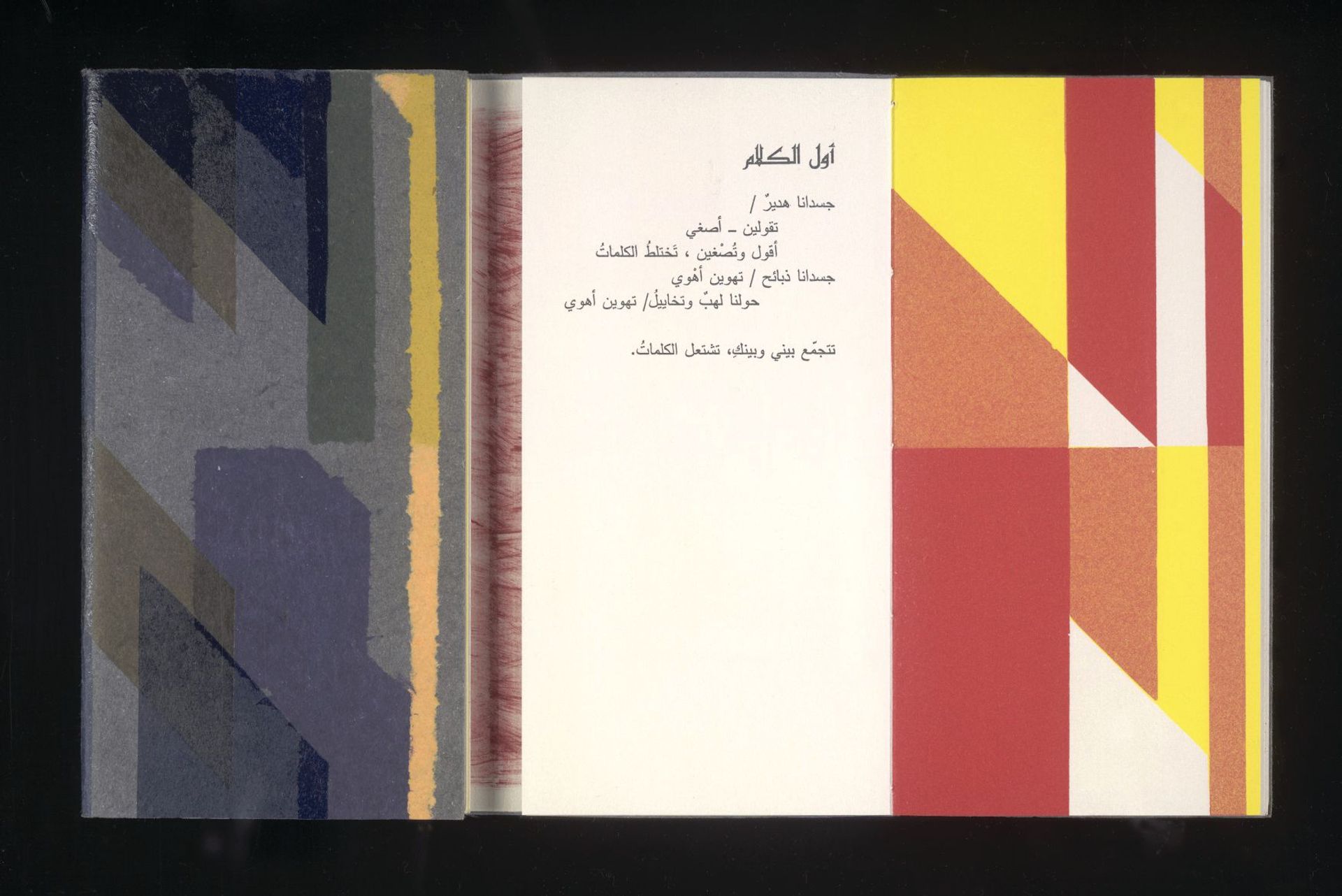

A 1992 book by the late Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata, illustrating Beginnings by Adonis

Courtesy of the artist

Her interest in these artists’ books developed during her time as a senior curator for Islamic and contemporary Middle East art at the British Museum. Porter, since retired, began to acquire books, alongside other works on paper. “The first one I bought was Blessed Day by Etel Adnan, in 1990 from Rose Issa [gallery] … when only aficionados knew the art that Etel was making alongside her writing,” Porter explains. “What instantly touched me was that in her concertina book, the words were a poem by a friend of Etel’s, the Tunis-based historian and poet Nelly Salameh Amri evoking the Lebanese Civil War. The lightness of touch, the way Etel highlights the words in colour belies their dark content. I exhibited it, alongside a number of other books that I acquired or borrowed, in the 2006 exhibition Word into Art.”

Porter subsequently learnt about the Iraqi tradition of dafatir (notebooks), as Iraqi artists call them, discovering an entire world of artists’ books initiated by the artist Dia al-Azzawi. “Distinguished by what I would call ‘Iraqiness’, these books talk about the history, politics, destruction and degradation of Iraqi heritage, and included within these dafatir are books inspired by Iraqi poets and medieval mystics. Azzawi influenced a whole group of artists: Ghassan Ghaib, Nazar Yahya, Hanaa Malallah and Mahmoud Obaidi,” Porter says.

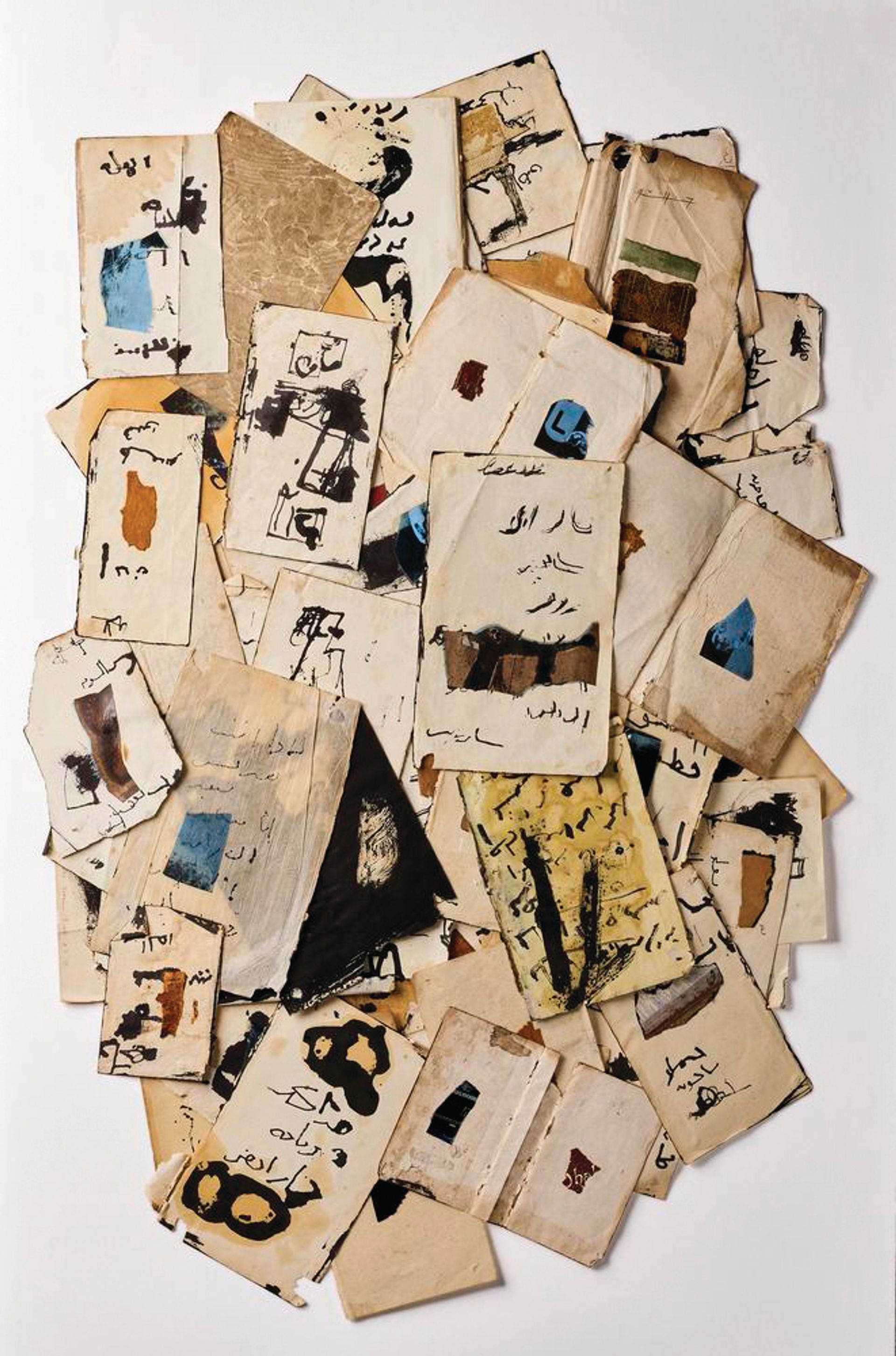

Sound Palimpsest (2003) was made by Issam Kourbaj using fragments of old books in response to the Iraq War © Trustees of the British Museum

The range of techniques and styles used, from concertinas to photo books, is also noteworthy. “There is a tactile quality to many of the books, a delight in the use of a particular paper, or in the craft of the making. A Colligation by Pakistani artist Muhammad Zeeshan [comprises] his series of flags of countries which have had complex relationships with the United States,” Porter says. “He uses the traditional techniques of Mughal miniature painting [that] trick you into thinking you are looking at embroidered threads, when they are in fact painted lines.”

Porter says she “let the works” create the four-section structure of the book. “The introduction attempts to set the scene overall and it is here that I make the connection with the French tradition of the livre d’artiste through the central role of Shafic Abboud, who arguably made the first books by a Middle Eastern artist.” The first section focuses on artists who work with the literary heritage of the pre-Modern era from across the Islamic world, ranging from the medieval One Thousand and One Nights to the Persian poetry of Hafez. “I love the way that literary heritage continues to have contemporary resonance,” Porter says.

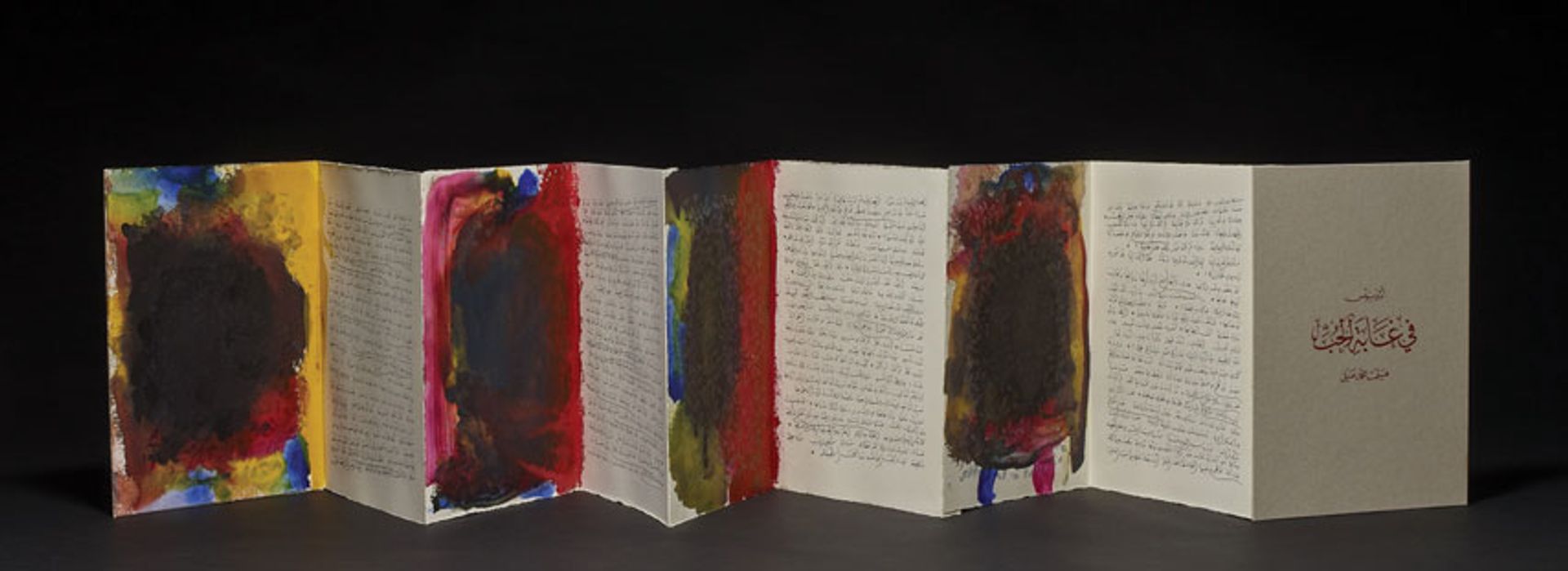

Himat Mohammed Ali’s concertina book containing Adonis’s poem In the Forest of Love

In the second section, Porter’s focus is on artists who work with Modern and contemporary poets. “I was really fascinated by the individual relationships that many of the artists have with poets or with their writings,” she explains. “The Syrian poet Adonis, in particular, has worked with so many artists. The Iraqi Paris-based artist Himat [Mohammed Ali], for example, meets Adonis on practically a daily basis and they plan and make books together.” The third and fourth chapters explore politics in a more explicit way Porter says, along with personal reflections or stories of migration.

Some of the works are also intensely personal such as the Beirut-born Abed Al Kadiri’s My Father’s Grave (2020), which was written during the pandemic and examines his relationship with his father. “It is a subject that he only felt able to express at this moment. It also connects strongly with his feelings about Lebanon,” Porter says. “Another personal story is the photobook of Diana Matar, Evidence (2014), in which she conveys the search for her father-in-law Jaballa Matar, kidnapped by the Gaddafi regime [in Libya] and who has never been found.”

Crucially, there are several works that resonate powerfully in today’s fraught climate. “Look at Dictionary Work (1997) by the brilliant Khalil Rabah, for example. It epitomises to me what it is to be Palestinian,” Porter concludes. The piece comprises an English dictionary covered with nails obliterating all but the word “Phi.lis.tine”.

• Artists Making Books: Poetry to Politics, Venetia Porter, British Museum Press, 160pp, £25 (pb)