The French artist Claude Monet (1840-1926) may be one of the most famous painters in art history but little is known about his private life. The art critic Jackie Wullschläger remedies this with a new biography—the first written in English—of the titan of Impressionism. Here, she explains how Monet’s “inner life”—notably his love affairs and friendships—informed his work and vision.

The Art Newspaper: How did a 2016 exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris spark the book?

Jackie Wullschläger: At the exhibition of Sergei Shchukin’s legendary collection, [Monet’s] Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, from Moscow, stopped me in my tracks. It’s a large early painting, heralding Impressionism in the dynamic action of light beating through foliage. I was intrigued by the five female figures, all modelled by the same woman, and the heart with an arrow engraved on the tree. It sparked my interest in Camille Doncieux, Monet’s first wife and muse, and her part in the beginnings of Impressionism. That research set me on the quest to write his full biography. Then in 2022, as I was finishing the book, I returned to the Vuitton to review a tremendous show pairing Monet with Joan Mitchell, which cemented my understanding of his last works, bringing painting to the brink of abstraction, and their legacy.

Jackie Wullschläger © William Cannell

Does the book fill a gap? In the sense that it documents Monet’s largely unknown interior life.

I hope so. I wrote it to answer my own question: who was the man behind the iconic images? It’s astonishing there’s been no full biography in English before, and none in any language exploring the relationship between his life and art. Monet’s paintings always seemed to me emotional, tumultuous and sensational, and I was fascinated to discover how he worked, battling his own temperament—thrusting, volatile, voracious, vulnerable—and also how hard he thought about intellectual and political currents.

Do you outline how Monet’s art and vision shifted according to the women in his life?

I see the contribution of each woman as fundamental. He would have been a great artist anyway, but how he developed was determined by his personal relationships. With Camille Doncieux he painted figures and busy extrovert scenes of everyday life; all that disappeared when she died. Alice Raingo’s contribution was subtle, pervasive and complex—their tempestuous early relationship found expression in Monet’s violent seascapes, while her nurturing, spiritual yet depressive sensibility affected his contemplative paintings of the 1890s-1900s. Finally, Blanche Hoschedé’s arrival in 1914 to live with the elderly lonely Monet made possible the crowning glory of the last Water Lilies.

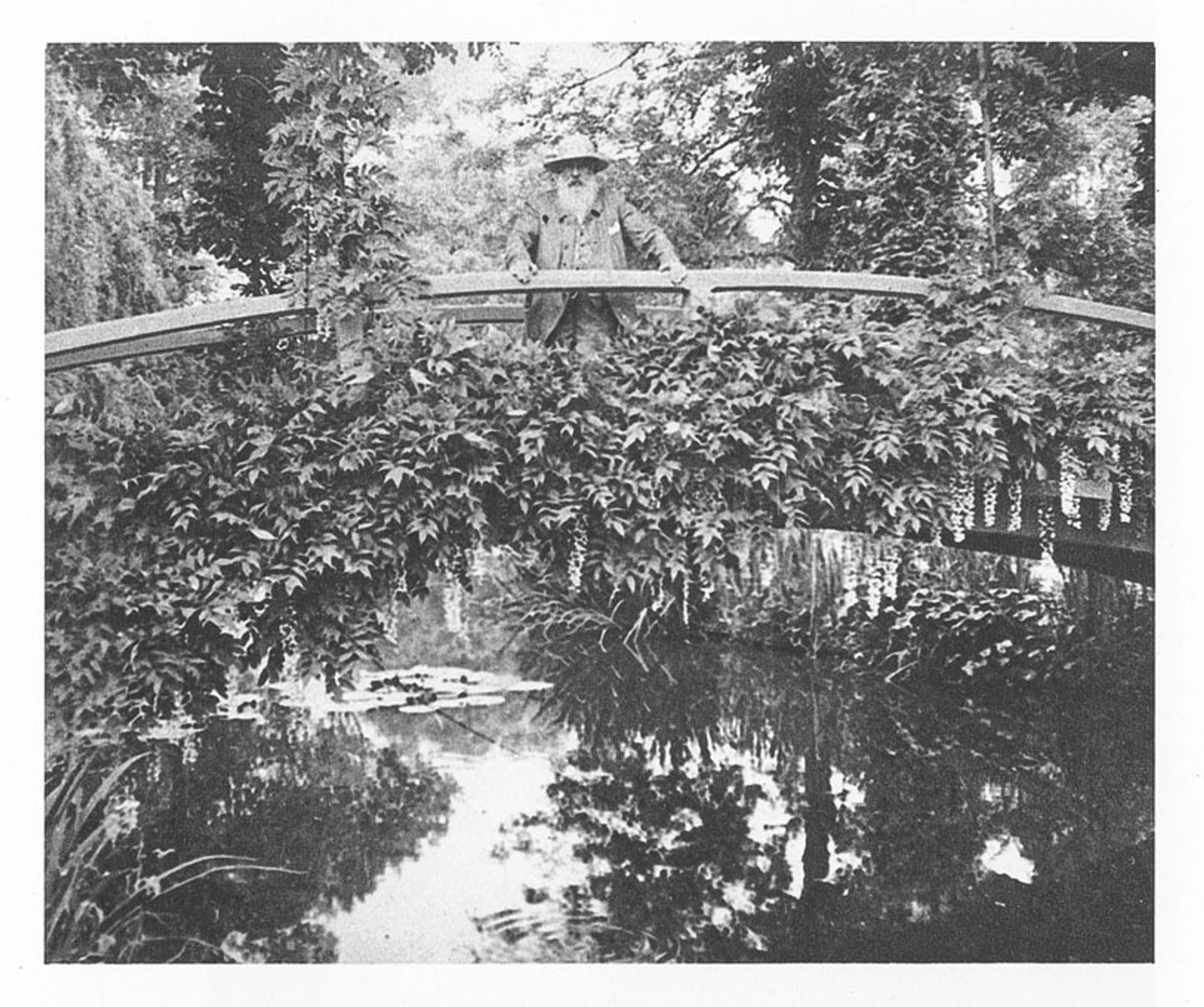

Monet standing on the Japanese-style wooden bridge at Giverny

The technical and thematic analyses of his paintings are fascinating. Was Monet always innovating stylistically? And was he progressing more by accident than design?

Monet wanted to render “what I myself have experienced, I alone”, and initially simply painted what gave him a visual thrill, “daring to express frankly” how he saw and felt the world around him: shadows in changing light in the snow in The Magpie (1868-69), a street of fluttering flags as a blur of colour and movement in Rue Montorgueil (1878).

But from the 1880s, refining Impressionism into more meditative painting, concerned with the passing of time, he was strategic in choices of subject and treatment. He very consciously innovated in inventing serial painting, building on his ability to capture fleeting moments and creating from it something symphonic. The series paintings are carefully selected contrasts—solid horizontal Haystacks then airy vertical Poplars, the stone of Rouen Cathedral then watery Mornings on the Seine, the tiny bridge over his Giverny pond then London’s grand bridges across the Thames.

He chose them all as vehicles to paint pure light and colour, showing how abstraction evolved from Impressionism, with its emphasis on subjectivity and free mark-making. In his 20th century Water Lilies, working with broad brushes on huge canvases, Monet pushed forward deliberately to make the picture plane primarily a painted surface rather than a site for representation.

Why was it important for you to discuss key contemporary heirs of Monet such as Adrian Ghenie?

The continuity yet change within the history of painting is a wonderful thing. Reading about contemporary painters’ responses to Monet, and talking with some of them, as various as Peter Doig, David Hockney and Bridget Riley, helped me grasp his long reach and why he matters for art now.

• Jackie Wullschläger, Monet: The Restless Vision, Allen Lane, 545pp, £35 (hb)