Hans Holbein the Younger got around. The son of the late-medieval painter Hans Holbein the Elder, the German Renaissance artist moved between Germany and Switzerland, then between the continent and England, before settling for good in the early 1530s at the court of the Tudor King Henry VIII. Skilfully managing to shift loyalties between Catholics and Protestants, he was one of the period’s great survivors. When he died in 1543, reportedly of the plague, he was not yet 50, but he had already outlasted a host of patrons and sitters destined for the executioner’s axe.

Holbein continues to get around in our own time. A couple of US touring exhibitions—one about Holbein himself starting at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, then another about the Tudors starting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York—have just wound down. And now this month, back in Europe, Holbein is the subject of two more major shows. At the Queen’s Gallery in London, the Royal Collection is putting much of its cache of Holbein drawings on display, for the first time in a generation, in Holbein at the Tudor Court. And in Frankfurt, the Städel Museum is mounting Holbein and the Renaissance in the North, which places the artist’s early religious works in a broader continental context, while arguing for a new interpretation of his early years in his father’s Augsburg workshop.

The Royal Collection’s 80 Holbein drawings, once gathered together in a 16th-century album known as The Great Book, largely came directly from the artist’s studio after his death, says Kate Heard, the Royal Collection Trust’s senior curator of prints and drawings, and is rich in sketches of both major and minor Tudor personages. Arranged chronologically, the 106-work show will feature a 1527 drawing, made using black and coloured chalks, of the writer and statesman Thomas More, and an influential drawing of Jane Seymour, Henry’s third wife, on pink-prepared paper. The immediacy of the Seymour drawing (around 1536-37) captures the physical frailty of the queen more than the completed portrait, now in Vienna.

A portrait previously believed to date from the late-1530s—going on show at the Städel Museum—could in fact be one of the artist’s last works Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

“Holbein was renowned for making his figures seem as if they were alive,” Heard says, and the show will reveal how he managed to do it by matching preparatory drawings with their corresponding finished portraits, also from the Royal Collection.

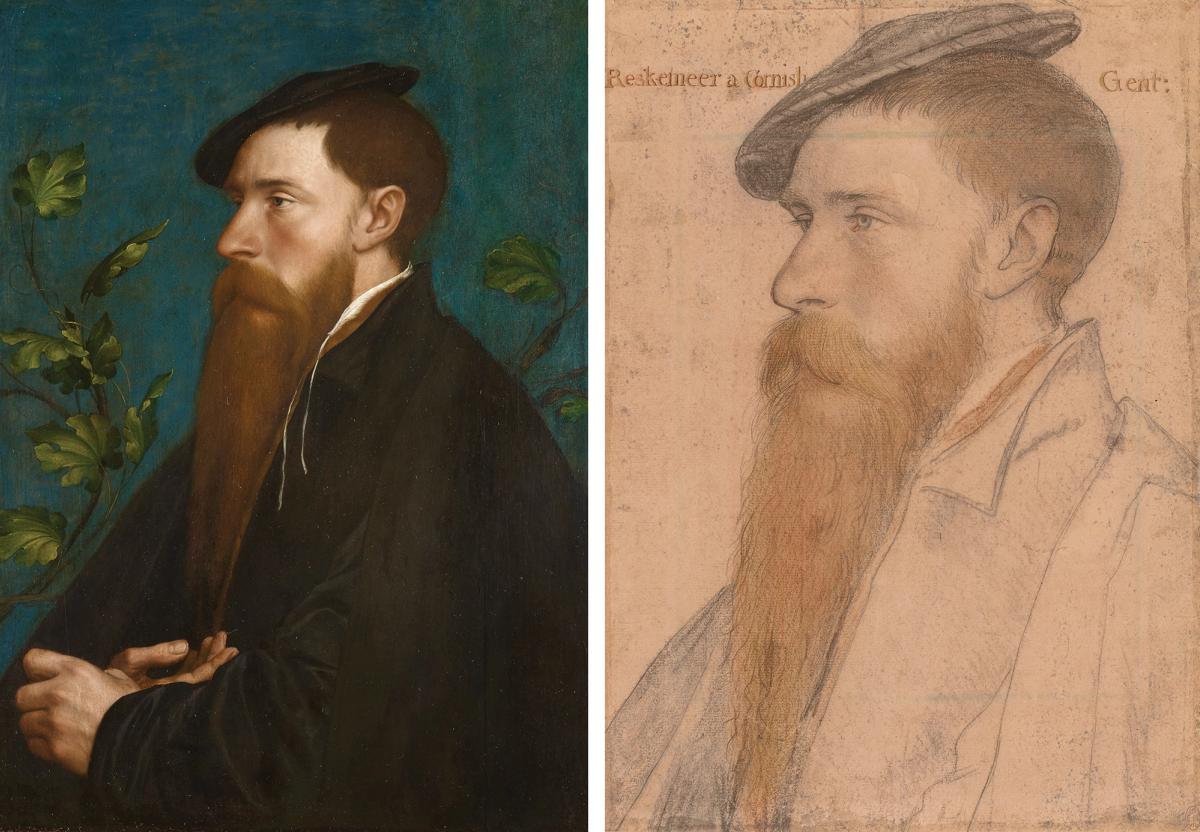

Heard cites a late 1530s painting of the Tudor courtier William Reskimer—“one of my favourites”, she confesses—which closely tracks the realism of the drawing. Holbein used his drawings as patterns for his panels, and the two Reskimers will be displayed next to each other at the Queen’s Gallery.

Heard has some news for Holbein scholars. In what was believed to be the mid-1530s, Holbein sketched an otherwise unknown Cornishman named Simon George, whose finished portrait, in which the sitter is shown holding a carnation, is now in the permanent collection of the Städel. Heard now believes that the sitter may in fact be a naval commander named George Cornwall, who was married in 1543—hence the carnation, which may signify that this is a marriage portrait—and that the new identity moves the Royal Collection sketch and the Frankfurt painting up several years, to not long before Holbein’s death. The curator now considers the George Cornwall drawing to be one of Holbein’s last.

Was Portrait of Marx(?) Fischer (1512) painted by a 15-year-old Holbein the Younger? Private collection

Meanwhile, the Frankfurt show, which travels next year to Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, will make its case for a re-examination of Holbein’s apprenticeship, says the Städel curator Jochen Sander. Its sensational addition is a recently resurfaced 1512 portrait of an Augsburg man named Fischer, last seen in the 1860s and now in a private collection. Bodo Brinkmann, the curator of Old Master paintings at the Kunstmuseum Basel, argues in the catalogue that the panel painting, which came out of the workshop of Holbein the Elder, is in fact by a 15-year-old Holbein the Younger, making it his very first known painting. These and other related new attributions incorporated into the show, Sander says, could lead to a reappraisal of the Augsburg phase that fostered Holbein’s talent.

The Frankfurt show, with nearly 190 works on view, will wind down with the Holbein painting that the Städel is still calling Portrait of Simon George of Cornwall (around 1535-40). Or is it George Cornwall, and was it painted in 1543? Sander, who is planning a trip to the Queen’s Gallery show, says he first learned about Heard’s theory this summer. “I’m looking forward to discussing it in person,” he adds.

• Holbein at the Tudor Court, The Queen’s Gallery, London, 10 November-14 April 2024

• Holbein and the Renaissance in the North, Städel Museum, Frankfurt, 2 November-18 February 2024