Art Week Tokyo’s new curated sales platform AWT Focus invites a guest curator to explore alternate art historical narratives through works from the participating galleries. With over 100 pieces by 64 artists, Kenjiro Hosaka’s Worlds in Balance: Art in Japan from the Postwar to the Present dynamically recontextualises the interweaving strands of art, craft and new forms of expression in Japanese visual culture. He tells us about five highlights in the show, open this week at the Okura Museum of Art.

Takuro Kuwata, Untitled (2021)

Kuwata is among a new generation of artists changing people’s attitudes toward craft and ceramics. He tosses aside concerns of utility in his ceramic objects, while simultaneously applying craft aesthetics to making art. He is also remarkable among those with a craft background for embracing the collaborative relationship between gallery and artist in developing his practice. In that sense Kuwata is similar to Shiro Kuramata and Shigeru Onishi in blurring the lines between different fields—but it’s worth noting that, prior to the modern period, the current word for “craft” in Japanese, kogei, was an overarching term for all visual expression.

Kishio Suga's Divergent Space (1975)

Courtesy of Tomio Koyama Gallery

Kishio Suga, Divergent Space (1975)

Japan has a long tradition of garden design, employing natural materials to produce a highly constructed space that generates profound insight into the structure of the cosmos. Through his installation practice, Suga succeeds in compressing the Zen garden into a form that can be realised anywhere in response to the conditions of the site. He prompts us to think about the ways techne—art, craft, technology—is already implicated in how humans engage and perceive nature.

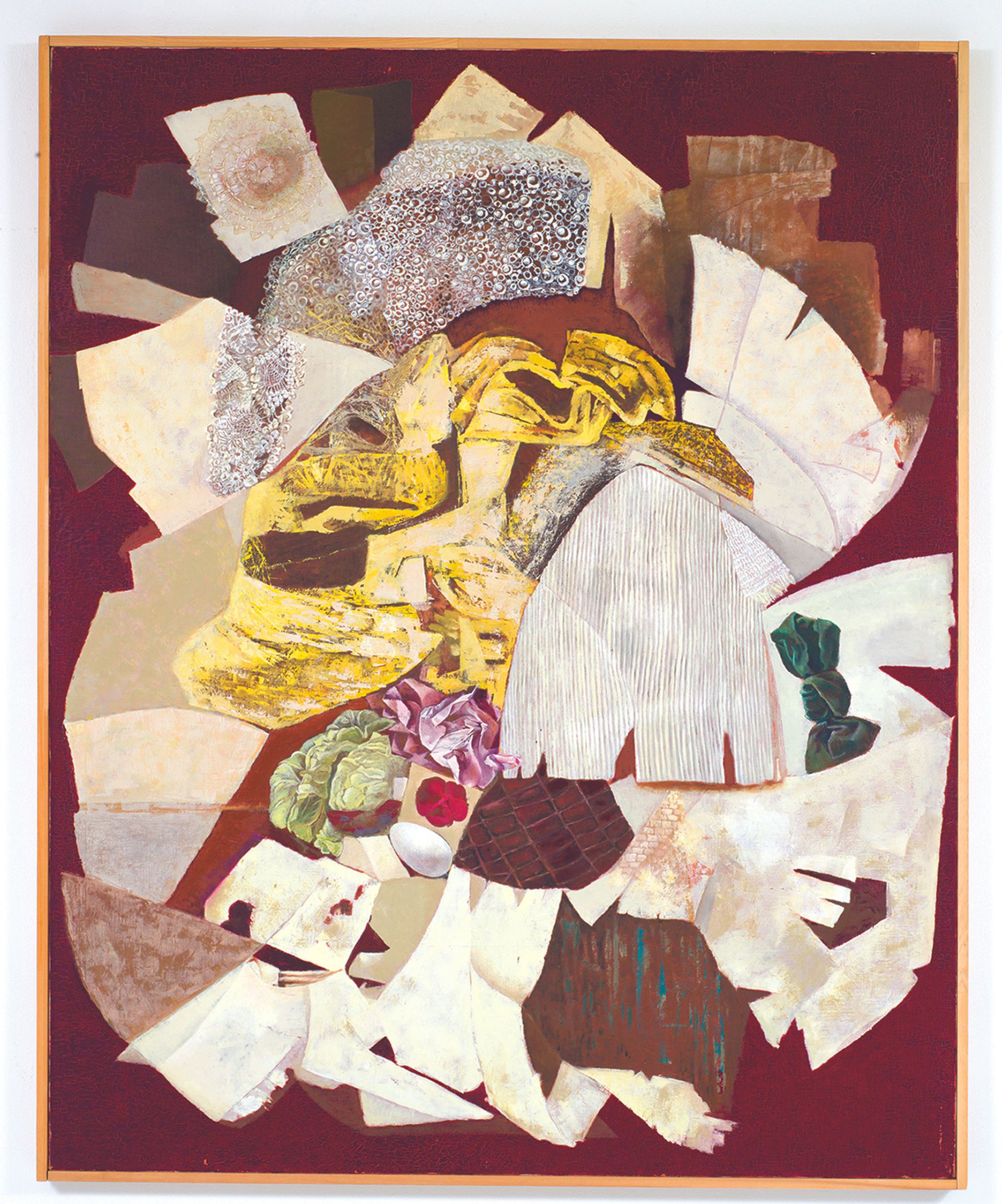

Yuki Katsura, Travel (1936/1978)

Courtesy of Tokyo Gallery + BTAP

Yuki Katsura, Travel (1936/1978)

A pioneer of abstraction in Japan, Katsura is one of a few artists whose careers span the pre- and post-war art scenes. Born in 1913, she started experimenting with abstraction in 1930s Tokyo and participated in the formation of a number of avant-garde groups at the time. Although she was featured in a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo in 2013, the strength of her works of this period, especially her collages, is still not fully appreciated. Later in her career Katsura was also one of the first Japanese artists to recreate lost works, as with this piece—a practice that has since become essential to our understanding of the art of the pre- and early post-war eras.

Shiro Kuramata, Cabinet de Curiosité (1989)

Courtesy of Take Ninagawa

Shiro Kuramata, Cabinet de Curiosité (1989)

Kuramata is a giant of post-war Japanese visual culture, but his place in the canon is unsettled because his practice doesn’t conform to institutional categories. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, still has no Kuramata works in its collection because no one can decide whether it’s art or design. In the meantime, M+ in Hong Kong has snapped up masterpieces including the Kiyotomo sushi bar (1988). But debating whether the work is art or design is reductive in the first place, whereas considering it through the lens of materiality and immateriality opens up more possibilities for interpretation. Kuramata’s quest to use material forms to escape materiality is shared by many artists from the 20th century onwards, extending to the rise of digital practices today.

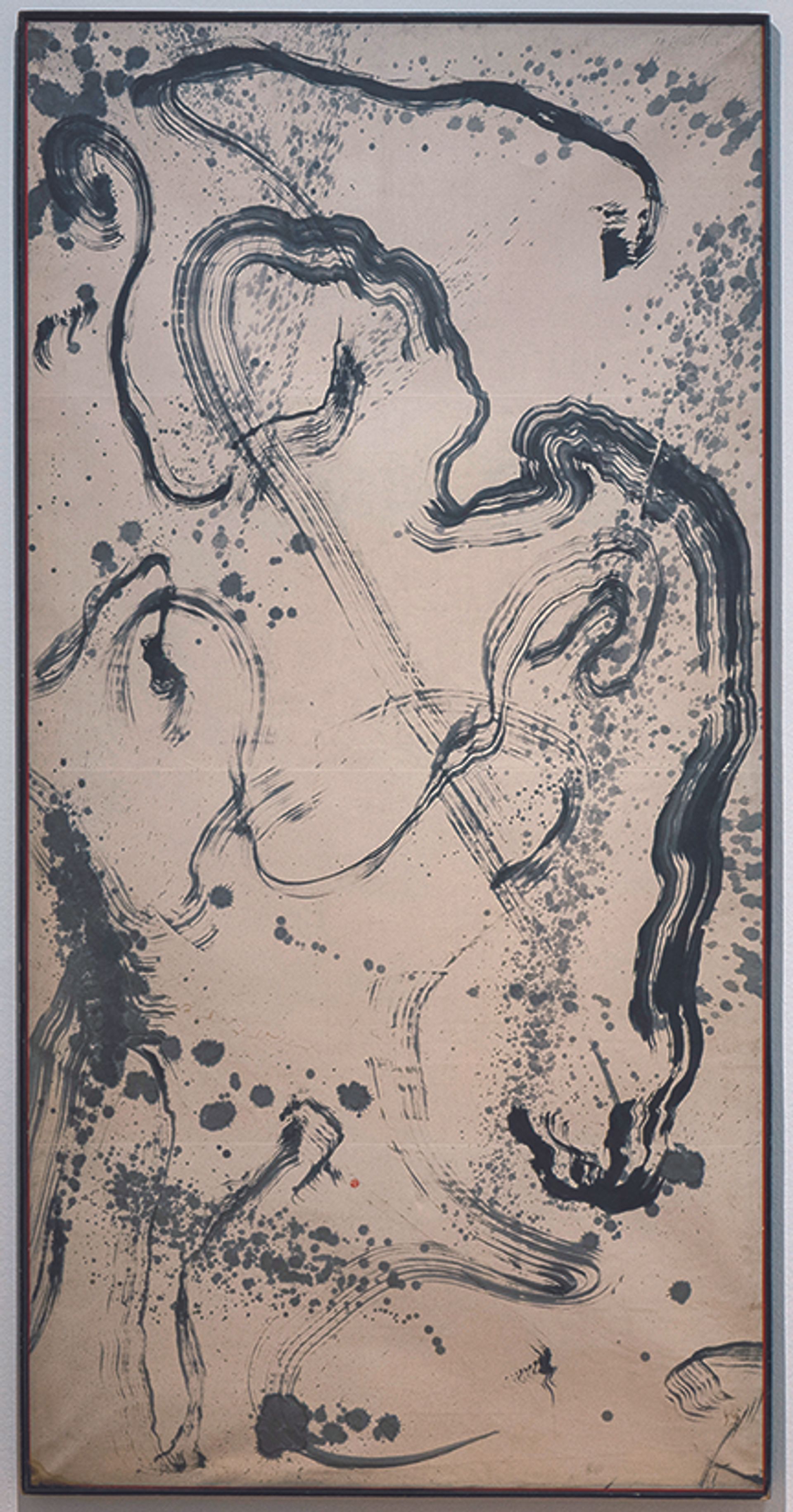

Shigeru Onishi, Composizione X3 (1962)

Courtesy of MEM

Shigeru Onishi, Composizione X3 (1962)

In recent years commercial galleries have taken the lead in researching artists who have been overlooked by history, as is the case with MEM gallery and Shigeru Onishi, who died in 1994. Onishi’s practice straddled photography and calligraphy, and he fell between the cracks despite having been championed by the critic Michel Tapié. Onishi used his training as a mathematician to innovate a radical mode of abstract calligraphy that strips its figures of all context. This piece, for example, can be displayed in both portrait and landscape orientations. It’s baffling that Onishi still hasn’t had a retrospective in Japan. I’d like to see his work enter more institutional collections here.

- AWT Focus, Okura Museum of Art, 2-10-3 Toranomon, Minato-ku, 2-5 November, 10am-6pm