A version of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, similar to the one at London’s National Gallery, is now the focus of an ambitious exhibition of still-life paintings at Japan's Sompo Museum of Art. The Tokyo picture was done three months after the London version.

Van Gogh and Still Life: From Tradition to Innovation (until 21 January 2024) provides an unusual opportunity to see Sompo’s Sunflowers in its context. When acquired for the museum in 1987 it cost £25m, then by far the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction.

The seller in 1987 was the heir of Alfred Chester Beatty, the American mining magnate who had extensive interests in central Africa, and his wife Edith. She had bought the Sunflowers for around £10,000 in 1935 and hung it in the drawing room of Baroda House, their London mansion in Kensington Palace Gardens, then known colloquially as Millionaire’s Row (and now as Billionaire’s Row).

The Tokyo Sunflowers above the sofa in the drawing room of the Beatty mansion in Kensington Palace Gardens, London (around 1953)

Credit: © Trustees of the Chester Beatty, Dublin

The Sompo’s still life exhibition, centred around their Sunflowers, was originally due to be held when the museum’s new extension opened in spring 2020, but the show was delayed because of Covid-19.

Entrance to the Sompo Museum of Art (2020 building), Tokyo

Until then the Sunflowers had been displayed in a surprising location: the 42nd floor of the Sompo insurance company headquarters. But the very top of a skyscraper was not deemed the safest place for a masterpiece, in the event of fire, and hence the decision to create a dedicated museum with street-level access.

Sompo’s Tokyo headquarters: until 2020 Van Gogh’s Sunflowers was displayed on the 42nd floor

Credit: The Art Newspaper

The new exhibition includes 24 other paintings by Van Gogh, nearly all on loan from Dutch museums. Among the coups is getting Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses (probably summer 1887) and Still Life with a Plate of Onions (January 1889), both from the Kröller-Müller Museum.

Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses had been dismissed as a fake in a 2003 Kröller-Müller catalogue. Nine years later research by the Van Gogh Museum, using new scientific techniques, led to it being fully accepted as authentic. Underneath the flower picture is a hidden Van Gogh composition which was painted over. It is of an unusual subject: two men boxing.

Van Gogh’s Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses (probably summer 1887)

Credit: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

The Sompo still-life show also includes 40 works by other European artists, spanning the 17th to the 20th centuries. These include Van Gogh’s contemporaries: Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Gauguin.

In the past there has been much discussion about whether the Tokyo Sunflowers was painted in late November/early December 1888 or January 1889. The difference of just a few weeks may appear trivial, but it is important, since it was on 23 December that Van Gogh mutilated his ear, leading to Gauguin’s abrupt departure from the Yellow House. Was the Tokyo picture done while Gauguin was still in Arles?

In the exhibition catalogue (which is partly translated into English) curator Shôko Kobayashi concludes that the Sompo Sunflowers was painted in late November/early December 1888. She points to two main factors, based on the Van Gogh Museum’s earlier investigations and her own research for the current show.

First, the Tokyo Sunflowers is painted not on conventional canvas, but on rough jute. Van Gogh and Gauguin had earlier purchased a 20-metre roll of jute, which was virtually used up by by early December. This makes it unlikely that the Sompo picture was done in late January 1889.

Secondly, in early December 1888 Gauguin completed Vincent van Gogh painting Sunflowers. Kobayashi believes that Gauguin made the portrait at the same time as the Sompo picture. However, although Van Gogh is depicted working from an actual pot of flowers, in reality he would have been copying his original, completed in August, when sunflowers were in bloom.

Paul Gauguin’s Vincent van Gogh painting Sunflowers (December 1888)

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh also went on to make a third version of the Sunflowers with a yellow background, which is now at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum. This was done in late January 1889.

Kobayashi goes on to recommend that the Sompo Sunflowers should be subjected to a full technical examination, including a detailed analysis of the jute support. She says this should help determine the “exact date of production” of the painting. Even more interestingly, it might reveal more about “the condition of Van Gogh’s life at the time of its creation”, during the crucial days when his tense relationship with Gauguin was deteriorating, just before the ear incident.

Anyone wishing to see the Tokyo Sunflowers will need to visit Tokyo, either during the current exhibition or after it goes back into the Sompo Museum’s permanent display. This is because there is now a Nazi-era spoliation claim for the picture, from the heirs of the German Jewish banker Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. He sold the work in 1934, and his descendants argue that this was a forced sale. They state that the painting is now worth $250m.

The Tokyo insurance company robustly rebuts this claim: “Sompo categorically rejects any allegation of wrongdoing and intends to vigorously defend its ownership rights in Sunflowers.” Whatever the eventual legal outcome, until then it might be imprudent to exhibit the painting outside Japan, in another legal jurisdiction.

In the meantime, the Sompo exhibition provides a unique chance to see the Sunflowers in the context of the artist’s other still lifes. We think we know the painting, since it is such an ubiquitous image—but it is always revealing to look at it afresh.

Other Van Gogh news:

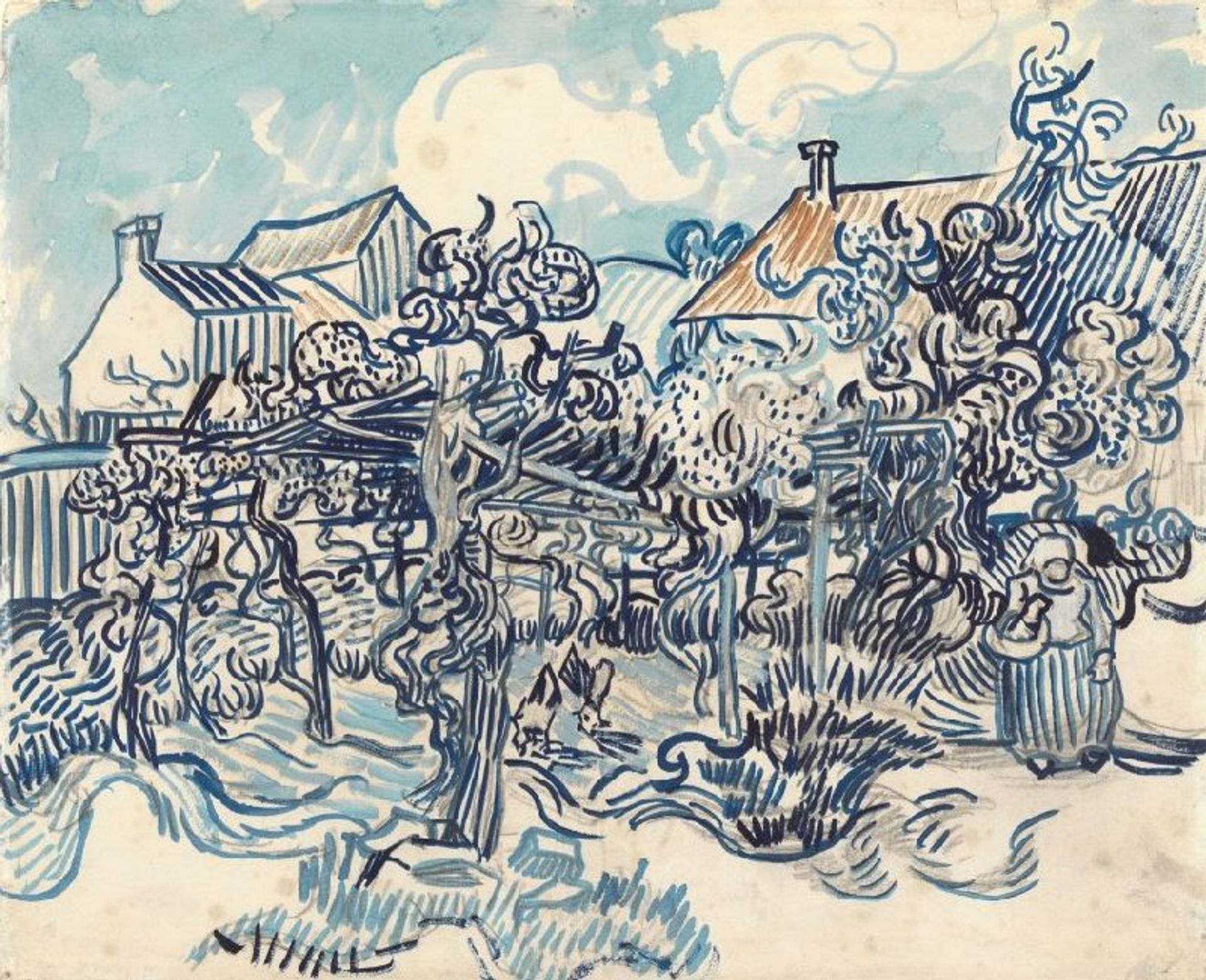

Thames & Hudson this week publishes Christopher Lloyd’s The Drawings of Vincent van Gogh, with over 150 illustrations. It covers Van Gogh’s entire career, with chapters devoted to the various genres. Although Van Gogh’s paintings are famed, his drawings are much less well known, partly because they can only be displayed for limited periods in order to prevent them from fading.

Van Gogh’s Old Vineyard with Peasant Woman (May 1890), from Christopher Lloyd’s The Drawings of Vincent van Gogh

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)