The American artist Ida Applebroog has died, aged 93. Her gallery, Hauser & Wirth, confirmed the news of her death and that she died in New York, but did not give a cause.

Applebroog examined power structures in her work across various media—including books, paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, films and installations—over her six-decade career. She described herself as a “generic artist” and an “image scavenger”, drawing references from mainstream media to create figurative, sometimes darkly humourous works that critiqued the construction of the female image in television, comics, fashion magazines, and art.

Although Applebroog made pioneering contributions to the feminist art movement, she resented the categorisation. “I have a real problem with feminism and art—this is something I’ve always objected to,” she said in an interview with Art21 in 2005. “I never liked the all-women shows. It does label us, ghettoise us.” Rather, she stated that her overarching focus was on “how power works—male over female, parents over children, governments over people, doctors over patients”.

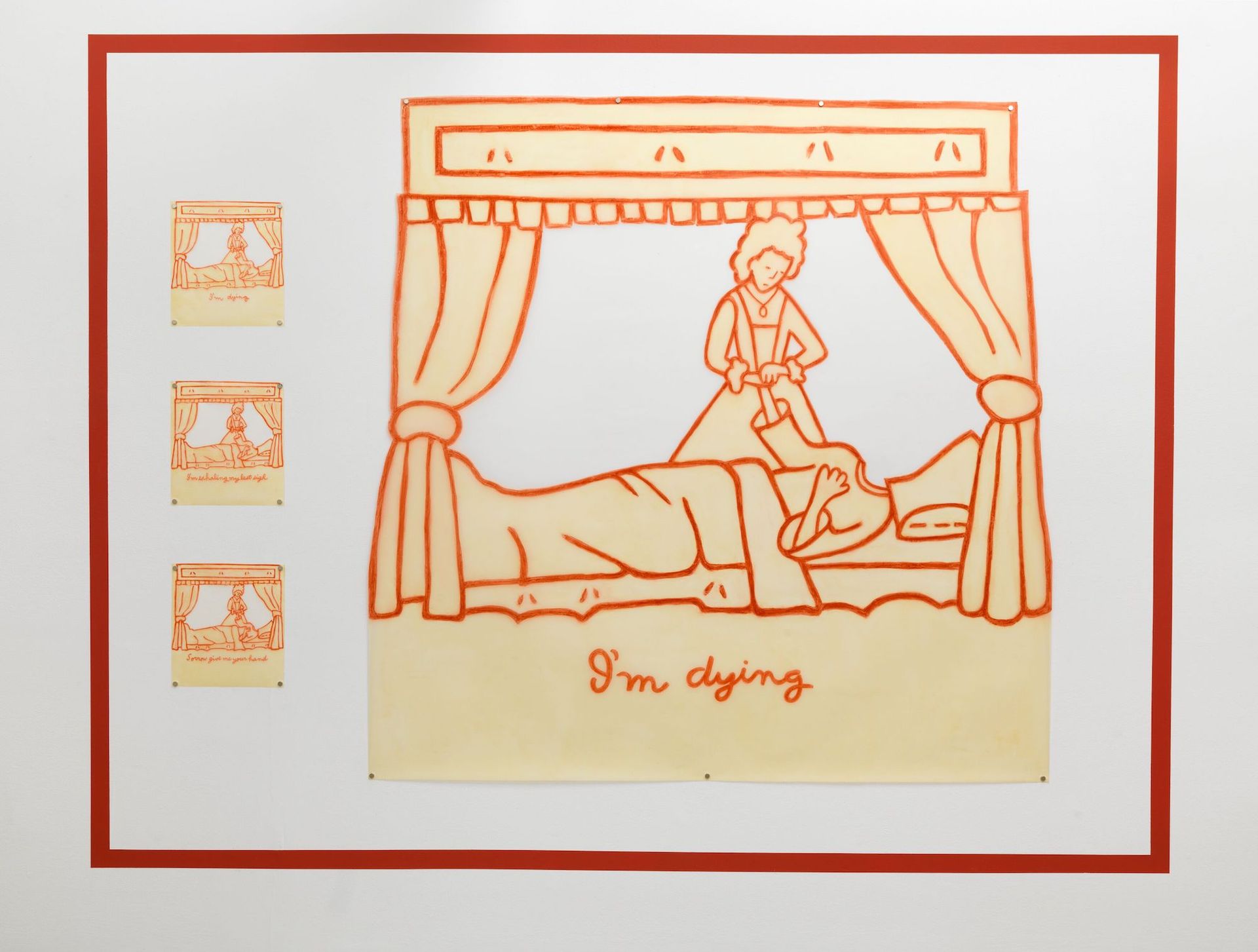

Ida Applebroog, Galileo Chronology: I'm dying, 1975 Photo: Ken Adlard. © Ida Applebroog. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Applebroog’s formal involvement with the feminist movement began when she attended the Feminist Artists Conference at the California Institute of the Arts in 1972. She later joined the Heresies Collective alongside figures like the curator Lucy Lippard and the artist Joan Snyder. She emerged in the New York scene in the mid-1970s, after publishing a series of artist books she titled Stagings, featuring simplified line drawings that critiqued various aspects of the female experience.

Applebroog often depicted women nude in domestic settings, or as disembodied genitals. Her first film, It’s No Use, Alberto (1978), was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1978. The work featured a series of suspenseful vignettes using shadow puppets and voice-overs, picturing scenes such as a woman having intercourse with a headless man. Around this time, she was also producing two-dimensional drawings and paintings as installations.

Ida Applebroog, Monalisa, 2009 Photo: Alex Delfanne. © Ida Applebroog. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Applebroog’s first solo exhibition was held in 1981 at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in New York—Feldman represented her for more than two decades. Her last solo exhibition with the late SoHo dealer, titled Modern Olympia, was held in 2002 and featured a series of monumental mixed-media works from the late 1990s that took Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) as a departure point.

Applebroog was born in the Bronx and raised in a tenement building by Orthodox Jewish parents who had immigrated to New York from Poland. She enrolled at the New York Institute of Applied Arts and Sciences in 1948 to study graphic design and simultaneously worked at an advertising agency, where she was one of relatively few female employees. She left after six months, citing rampant workplace sexual harassment, and began working as a freelance illustrator.

Ida Applebroog, Everything is Fine, 1990-93. Installation view at the Brooklyn Museum © Ida Applebroog. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

In 1950, she married her childhood sweetheart Gideon Horowitz. With their four children, the couple relocated to Chicago, where Applebroog studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago between 1965 and 1968, and later moved to San Diego. In 1969, she suffered a breakdown and checked herself into a mental health facility for several weeks, opting to make drawings rather than attending occupational therapy.

During this time, Applebroog made over 150 ink sketches of her vagina, which her studio later recovered from the hospital. The works, which were a product of a ritualistic practice, were shown alongside other bodies of work at the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami in 2016.

Applebroog has been represented by Hauser & Wirth since 2009 and had a major solo exhibition in the gallery’s Upper East Side space in New York the following year, titled Monalisa. The exhibition featured a room-sized structure plastered with more than 100 drawings based on the aforementioned series of sketches from the late 1960s. Her most recent exhibition was held at Hauser & Wirth’s Somerset space in 2022; titled Ida Applebroog: Right Up To Now 1969–2021, it encompassed several key eras of her career.

Ida Applebroog, Gas Mask, 2021 Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Ida Applebroog. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

“Ida has been a powerful force within the feminist movement since the 1970s, forging her own unique identity as an artist and woman, mother and wife,” Manuela Wirth, the co-president of Hauser & Wirth, said in a statement. “Relentless in her capacity for expansive visual experimentation, she interrogated themes of violence and power, human relations, her own body and domestic space.”

Iwan Wirth, the gallery’s other co-president, added, “Her emotionally disruptive and fearless approach to making art has been an inspiration to many generations, intensely personal, honest and raw. We are eternally grateful for her humour, wit and radical introspection, presenting the absurdities of life as it is.”

Applebroog’s work is held in the permanent collections of many major institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum.