Frank Walter was many things to many people. He was an artist; an environmentalist; even a supernatural being. To some in his home country of Antigua, he was “Crazy Man Frank”; he believed himself to be a descendant of Julius Caesar, Charles II and Franz Joseph of Austria, to name but a few. He was certainly complex but, perhaps above all, says the curator Barbara Paca, he was “a visionary”, much of whose remarkable world has yet to come into public view.

This month, an exhibition curated by Paca at London’s Garden Museum introduces Walter to new audiences, bringing together more than 100 paintings and sculptures, including many that have never been exhibited before. The exhibition, which is organised in collaboration with David Zwirner gallery, takes visitors deep into Walter’s universe, using an immersive installation to bring to life the spaces in which he worked and showing how he used his art to grapple with subjects ranging from nature to folklore and identity, often all at the same time.

Born in 1926, Walter had a successful career in the agricultural industry before he became an artist, rising to become the first Black manager of a sugar plantation in Antigua. Passionate about “the people who tilled the soil”, Paca says, he travelled to England, Scotland and mainland Europe in the 1950s—learning about agricultural technology while also facing severe discrimination—before returning to pen an environmental manifesto and run, unsuccessfully, for prime minister. In 1993, having lived on another Caribben island, Dominica, and then elsewhere in Antigua, he moved to a remote house in the rural area of Bailey Hill, where he focused on his art.

A preoccupation for Walter was his complex heritage. He was a descendant of both European plantation owners and enslaved Africans, and he grappled with this through his art and writing. He invented an elaborate genealogy tracing a lineage back to Western royalty, which is unpacked through a film and display case in the exhibition, and created self-portraits of himself as Charles II, St John the Baptist and more. He “saw himself as a white man”, Paca says, but also had a deep fascination and connection to Black Caribbean culture, painting pictures of Obeah men and women—practitioners of a Creole religion that developed during the colonial period—among other subjects. On Dominica, he had even become known among local children as a marabunta: a creature with magical powers.

In nature, meanwhile, he found a constant. An immersive space at the Garden Museum’s show reimagines the house on Bailey Hill, which Walter designed as his personal paradise; he filled its corridors with his sculptures; created a studio that jutted out into the land with no roof or walls; and nurtured the plant life proliferating in the grounds outside.

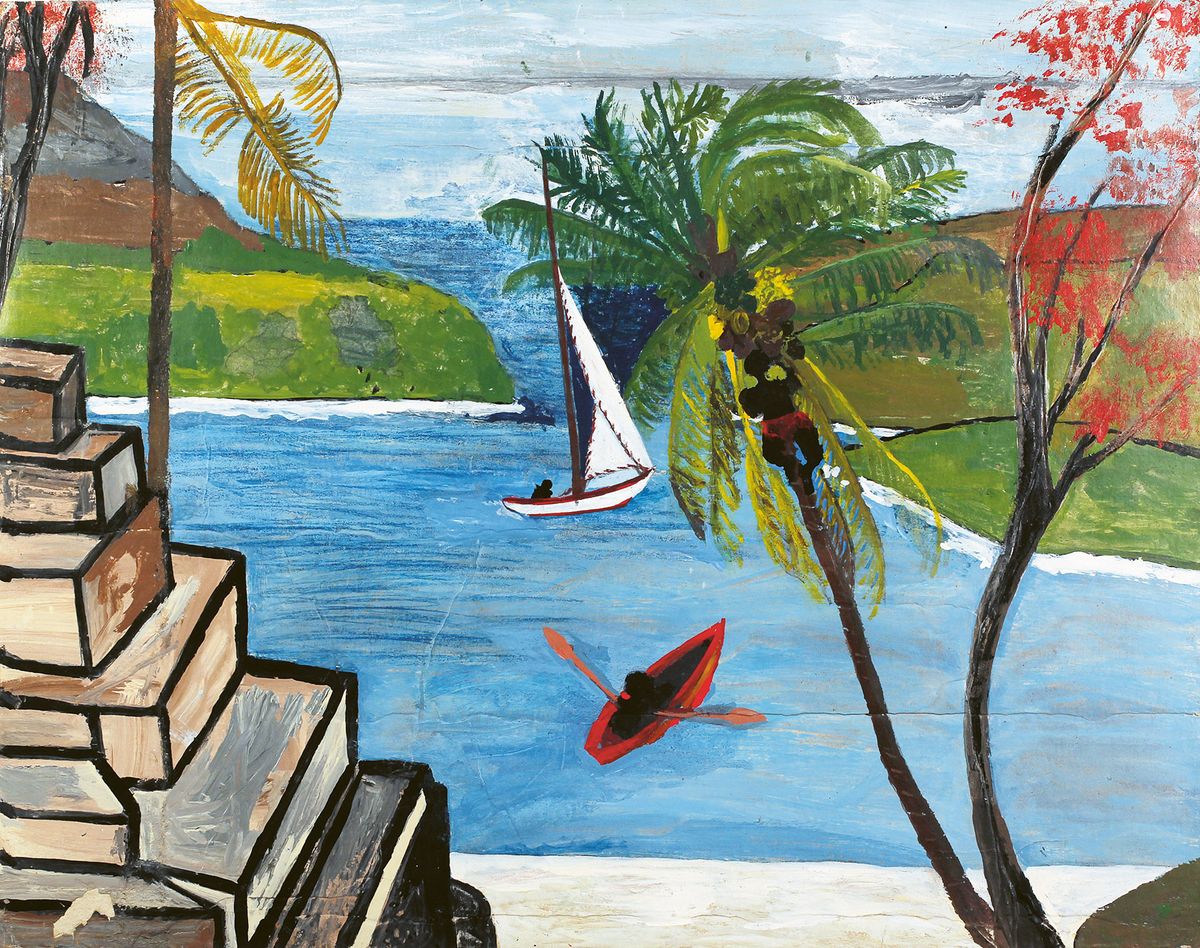

Here, in his role as artist-gardener, he painted fruits and plants, semi abstracted or pared down into simple forms. He also rendered a series of dreamlike Antiguan landscapes on Polaroid film cartridges—examples of his ability to work with colour and scale.

Walter worked from memory and used his art to distil the many layers of his life. His Milky Way Galaxy series arguably represents the culmination of this effort. In it he both pondered outer space and used it as a prism for tapping into his past. In Moon Crater (1994)—on view in the exhibition—long shards of yellow, white and grey cut through a charcoal landscape while, in the background, a mountainous area burns red. For Paca, these are references to locations Walter knew well. “He inhabited that landscape, and he was obsessed with those mountains,” she says. “Here, he’s actually time travelling to that place.”

Frank Walter, Moon Crater (1994), an example of how Walter used the theme of outer space to investigate his biography

Photo: © Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner

Paca met Walter in 2003 and was given access to an expansive collection of his paintings, sculptures, drawings and recordings, as well as a 50,000-page archive, which has made the exhibition possible. She visited the house on Bailey Hill and describes her encounter with Walter there, the artist emerging wearing a royal blue curtain decorated in bright orange owls—an object that also features in the show.

“Walter didn’t want to be like anyone. He didn’t want to be excluded from anything that he was,” Paca says. What he did want, she explains, is to be present for others, with one of the most resounding aspects of his legacy being the support he offered to fellow artists.

• Frank Walter: Artist, Gardener, Radical, Garden Museum, London, until 25 February 2024