We all use our garb to send out often mixed messages, and artists are no exception. From Rembrandt’s multiply-costumed self portraits to Frida Kahlo’s Tehuana dresses, the relationship of artists to their clothes has always been an especially complicated one.

And no one has charted the relationship of artists and clothes more closely than perhaps the writer, fashion critic and curator Charlie Porter. His first book, What Artists Wear (2021), zeroed in on the sartorial choices of Modern and contemporary artists to explain how garments can become potent tools of expression in their own right.

Now Porter has set his sights on the Bloomsbury Group, that early-20th-century band of British artists and intellectuals who included the writer Virginia Woolf and her artist sister Vanessa Bell, the artist Duncan Grant, the economist John Maynard Keynes and the writer E.M. Forster. This highly influential cultural collective has been shrouded in much myth, misconception and snobbery, both during their lifetimes and by subsequent generations, who have often gone to pains to obscure their experiences of queerness and self-expression as well as some of their less appealing attitudes towards race, class and privilege.

Tim Walker, Rebel Riders, at Charleston, 2015

Porter grapples with and unpicks all of the above in Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion, a new book and exhibition that re-examine the group through the prism of their garments. Reciprocally he also shows how contemporary designers such as Kim Jones and Rei Kawakubo have been inspired by the group’s radical ideas and art rather than the more superficial Bloomsbury “look” embraced by middlebrow manufacturers of pastel paint ranges and soft furnishing fabrics.

Among the show’s highlights is the juxtaposition of Grant’s works with the garments they have inspired, such as his abstracted Lilypond Screen now set in motion on a Jones jacket for Dior, or the way in which the morphing identity of the protagonist in Woolf’s Orlando finds expression in Kawakubo’s eruption of white ruffles bursting out from a shell of strict black tailoring.

In 1920, Woolf invited fellow writer T.S. Eliot for a country weekend, instructing him to “please bring no clothes”. She wasn’t suggesting that he turn up naked (although there was much flesh-baring among the group) but that Eliot would not have to observe the stifling sartorial conventions that still had the British upper and middle classes in a stranglehold. In both this book and show, Porter demonstrates how the ways in which Woolf, Bell and co thought about and wore their clothes was a key part of their intellectual—and sexual—revolt against the late Victorian society into which they had been born.

Queer and subversive

But it is complicated. Woolf hated fashion but was fascinated by clothes. While Bloomsbury patron Ottoline Morrell wore increasingly exaggerated clothes to fashion her own look in a way that was both admired and mocked by her companions.

Porter offers an unblinking contemporary gaze as he dives into the extent of the group’s queerness and subversiveness but also doesn’t blanch from some of their less than savoury escapades, such as dressing up as African potentates or the subjects of Paul Gauguin. He also flags up the irony that their philosophies of free and good living were underpinned by the labour of their domestic servants. But these anomalies are set in the context of a problematic past era and not allowed to blot out the achievements of these sexual and intellectual pioneers.

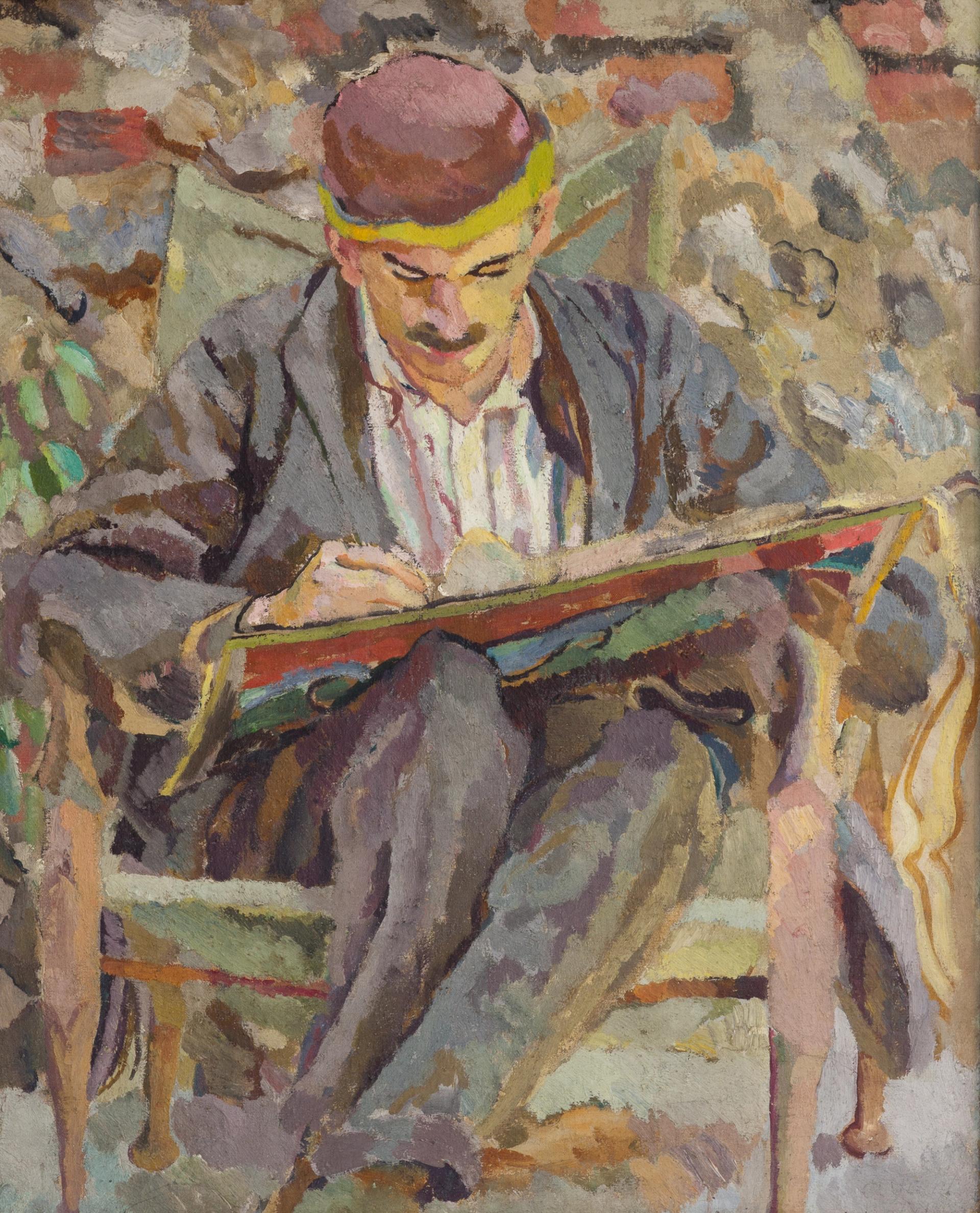

Duncan Grant's Portrait of John Maynard Keynes (around 1917)

© The Estate of Duncan Grant DACS

By casting off their Edwardian corsets for free-flowing garments, often hand-crafted and extensively repaired, the Bloomsbury women were signalling their sexual and creative experimentation. Woolf’s loosening of her stays reflected both the flourishing of her queerness as well as her format-busting writing. And the liberated line of Vanessa Bell’s handmade garments and her violent colour combinations (“they almost wrenched my eyes from their sockets” observed Woolf in 1916) also found expression in vivid, abstract rug and cloth designs for the Omega Press, as well as onto her canvases.

Likewise, the men navigated the tension of tailoring in various ways. Wayward self-portraits and photographs of Grant reveal his clothes to be in a constant state of unravelling, or simply not there at all. Maynard Keynes embraced and played with the power of the suit: a delicious portrait by his then lover Grant shows him formally besuited and working on mathematical theories while also rocking a saucy pair of patent pumps.

Not only has Porter redefined and rebooted Bloomsbury as a precursor for contemporary fluidity but, in true Bloomsbury spirit, he also blasts aside conventional notions of beauty and probity. One of my favourite exhibits is two cigarettes plucked from the pocket of Morrell’s exaggeratedly mannish (but beautifully handmade) jodphurs.

It is appropriate that this exhibition is not being held in Charleston, the Sussex farmhouse that has become a Bloomsbury shrine, but instead inaugurates Charleston’s new outpost in a former 1930s Citizens Advice Bureau building in the centre of Lewes. In these pared-back surroundings the art, life and clothes of Bloomsbury are given a fresh life and relevance.

• Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion; Charleston in Lewes, until 7 January 2024

• Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion, published by Penguin, £20 on 7 September, £20