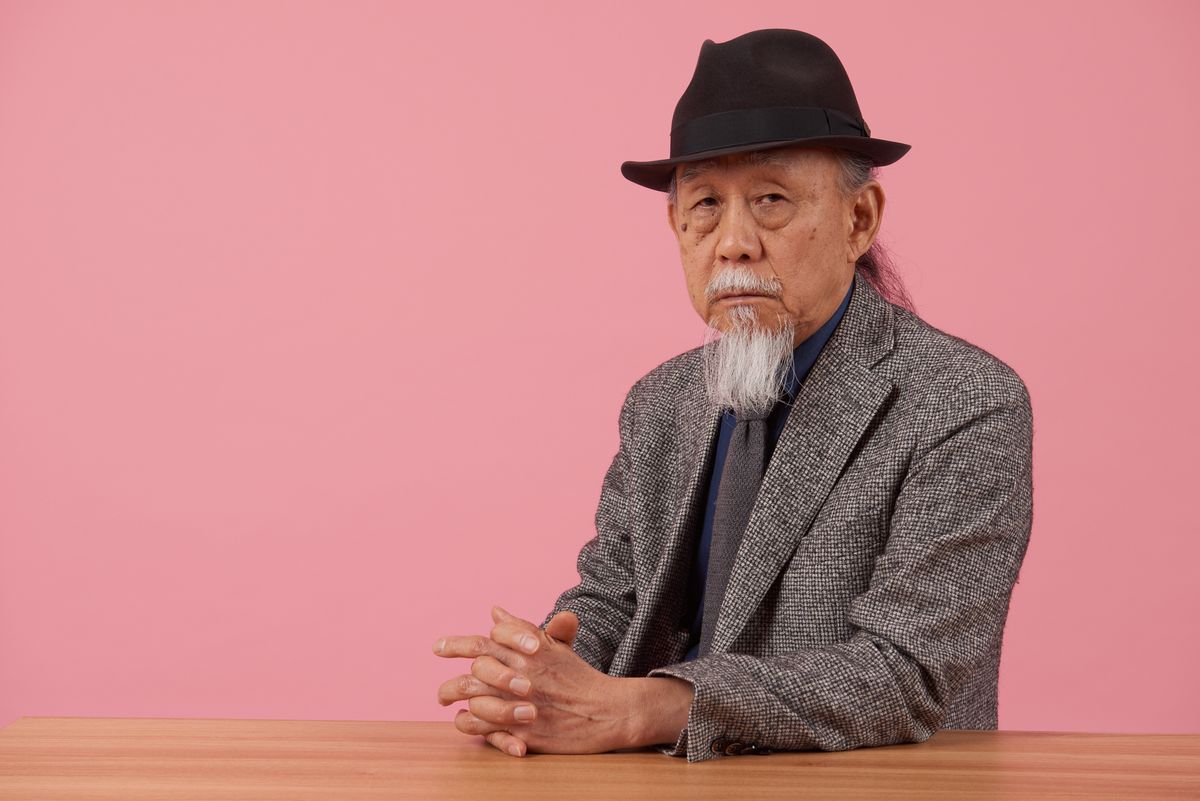

After more than five decades, the art world is properly catching up with Sung Neung Kyung. The 79-year-old South Korean artist is included in the major group exhibition Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, which opened at the Seoul’s Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), and is now on show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York (eventually travelling to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles on 11 February). Alongside this, he has a solo show in Seoul at Gallery Hyundai and is finalising plans for a New York solo exhibition at his other gallery, Lehmann Maupin, due to open in 2024—his first-ever solo show outside South Korea.

Sung signed to both galleries only in the past 18 months, and was previously unrepresented. Indeed, for much of his life, he has flown in the face of both the government and the mainstream art world, embodying a counter-cultural spirit of a generation whose first decades were shaped by Japanese occupation, the Korean War and the subsequent military dictatorship.

Sung’s body of work can be defined by its use of mundane objects, such as newspapers, as well as acts of erasure and endurance. His work at the Guggenheim includes one of his best-known, Newspaper: from June 1, 1974, in which he hangs up pages from a Korean daily newspaper and removes sections with razor blades. The work comments on the state of being under an repressive authoritarian regime; it also questions the power and authority held by the media. Performance is a significant part of Sung's practice too, and he will perform this work at the Guggenheim on 17 and 18 November.

At Gallery Hyundai you staged a newspaper reading performance in which dozens of participants around the world will read from local newspapers. Can you tell me more about this and why you wanted a global group of participants? Is a global audience something you have always desired?

My Reading Newspaper performance concept book was acquired by Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art in 2019. In 2021, the same museum staged the seven-person Reading Newspaper performance using that concept book. The city of Ansan, where the museum is located, had a significant population of foreign labourers. I highlighted that characteristic and asked two women from Southeast Asia to read newspapers or newsletters from their native countries in their languages; they read and scrapped out materials in their languages. Subsequently, this performance served the genesis for this collective Reading newspaper performance with 100 individuals from around the world.

Globalisation, which progressed since Alexander the Great, has steadily increased the number of foreign immigrants in Korea to an undeniable amount that immigrants who satisfied certain requirements were given the right to vote. Reading Newspaper with 100 participants confirms this social phenomena in Korean and simultaneously amplifies the presence of foreign immigrants through their voices. I included a group of residents from all around the world to appeal to Koreans that foreign immigrants, too, are responsible citizens.

All these years later you’re still performing—do you intend to continue?

Of course. Thankfully, performance is not result-oriented. Even when I grow frail, I would be able to show new representations of my bodily existence. Beautiful bodies and strong bodies are not the only bodies. Emaciated bodies and exhausted bodies are bodies, too. I intend to show the process of decline, not the result, in my performances using emaciated and decaying bodies. It is a path no one has traveled yet. Would there be discontent if I were to follow that path? Starting from the performance I showed as a young performer, towards the performance of an aged performer, I hope to present new performances through that process.

The significance of newspapers has changed a lot since you began your art practice. To a new generation they take on different meanings. Do you think this also changes the interpretation of your work?

The paper medium is in a predicament. This must be the case in America as well. In that respect, young artists’ interest in the paper medium will likely diminish. The activation of digital will transform the ideas surrounding other media. One of these days, printed newspapers will disappear. I continue to use printed newspapers in my work, as I have nostalgia for that distinct smell of paper. Such characteristics endow a somewhat different sensibility upon the digital generation. I don’t know if that will lead to a different interpretation. However, do I have to care?

Yes there is a different sensibility to newspapers in a younger generation. That being said, your work also draws attention to the vehicle of content, while destroying or obscuring the content itself. In an age where we are subjected to constant, often banal, information, mediated by digital devices owned by tech conglomerates that harvest data and spy on us, this approach also feels prescient. What do you make of this digital-era reading of your analogue work?

Newspapers during the time of my Reading newspaper had been controlled by the authorities. However even such newspapers had still endeavoured to report on the severe travails of Korean society. For example, editors headlined insignificant articles to ingratiate themselves with the authorities, while important and unfavourable information were tucked away in the margins of the newspaper. Those who recognized their effort were the young news vendors on the streets. They underlined these critical articles with a red marker pen–though these were promotional strategies to sell newspapers–to emphasize their importance while demonstrating the courage to re-edit the editor’s edits. In other words, the office chair and the street vendor’s stand collaborated.

Along with the democratisation of Korean society, publications in Korea gradually obtained autonomy. However, the major conglomerates of “digital devices” emerged soon after, “where we are subjected to constant, often banal, information,” as you addressed. The rampant dissemination of “fake news” has made it difficult to determine the truthfulness of information. In recognition of this, my concept book text at Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art specified that digital information on mobile phones is “read and deleted”–not “read and cut out” as in printed newspapers–and executed in front of a screen, allowing the viewers to witness the process. This has been performed at the seven-person Reading newspaper performance.

I believe you can understand my intention, although not entirely certain, to engage with concerns regarding the algorithms of the digital conglomerates as well as the falsity and banality of information. However, in the Reading newspaper performance with 100 participants, the act of “reading and deleting” digital information is not included. That is to concentrate on the voices of the foreign residents in Korea. If I am given a similar opportunity in the future, I intend to continue with the performance of “reading and deleting” digital information. The assessing and "reading” of my “analogue” Reading newspaper by the “digital-era” is entirely up to the “digital era.” I am humbled by their assessments and reading. The artist is the one who is “doing,” and the “reading” is done by others.

You have found gallery representation relatively far into your career — had you received offers previously from commercial galleries? Why did you decide to sign with a gallery now? And made you decide to sign with Gallery Hyundai and Lehmann Maupin?

In 1991, I had a solo exhibition entitled S's Posterity: Botched Art is More Beautiful at Samduk Gallery in Daegu. Samduk Gallery, however, was not a commercially active, or sales-oriented, gallery; it was more like an exhibition space that organised shows and displayed artists’ work.

The commercial gallery, which prioritises sales, was a more recent development. Up until that point, Korean art scene had not been professionally commercialised, excluding three or four major galleries. One of them in the 1970s was Gallery Hyundai, although I was not the gallery’s target artist. No commercial gallery embraced experimental art at that time, and the entry was challenging for artists like myself. Thus, I can say I never once collaborated with such galleries.

It seems natural for me to lately begin collaborating with and signing with galleries. I assume it is the effect of the Guggenheim show. Guggenheim’s recognition of Korean experimental art as a significant art historical movement has allowed many artists, including myself, to be recognized with importance. As a result, I believe commercial galleries have approached me with enlarged interests. Throughout that process, naturally, I began working with Lehmann Maupin—a prominent American gallery. I thought my participation in Lehmann Maupin’s program would be an opportunity for Korean art, as well as for myself, to expand globally.

How did you sustain yourself as an artist for so long without gallery representation?

I continued my art practices, despite not having a gallery representation, because I was immature at the time, not knowing how to live in this world. I never thought about making ends meet. My parents, when I was young; my older brother and his wife, when I had grown; and my wife, after marriage, nourished me. My wife used to be a primary school teacher. So, without any interest in how to make ends meet, or how to live life, I occupied myself with art-related thoughts, from dawn till dusk, whether or not at work.

I never received grants; however, in 2001, I had a solo exhibition/retrospective entitled Sung Neung Kyung: Art is the Shadow of Distraction at Arko Art Center. Then in 2009, Baik Ji Sook, director of Arko Art Center, purchased Newspaper: from June 1, 1974, on, which marks my first sale. Since Arko Art Center’s acquisition, many museums have purchased one or two work/s annually up to a recent date. The institutions that have acquired my work include National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Seoul Museum of Art, and Daejeon Museum of Art. There has not been a private collector. The museums have approached me first with requests for acquisitions, without the assistance of galleries.

You famously captured the political spirit of a repressive military dictatorship in Korea. Some people view Yoon’s presidency as a reactionary shift that is even threatening Korea’s cultural institutions. What do you make of this current political moment in Korea?

It is difficult for me to answer since this is a rather political question. I believe the present administration is different from the repressive one that presided in the 1970s and 80s. We cannot repeat the past.

The current government does recur to right-wing tendencies; however, I don’t see this as a return to the past’s oppressive military dictatorships. Because of the right-wing tendencies of the current government, those with progressive views may be dissatisfied. I understand that. Yet, since the administration is just a little over a year old, I want to remain neutral and assert that I am who I am. Departing from the political discourse, I want to advocate for and respect my position. I am who I am. Nevertheless, I will roll-up my sleeves if a military government of the same kind sets in.

Are artists in Korea still making work commenting on contemporary politics? Or do you think the relationship between art, politics and personal life has now shifted, and that making explicitly political work is redundant?

Recently, I watched many artist exploration programs on YouTube; it was a good opportunity to come across young artists. It seemed they had no aversion to selling their work; their pieces were apolitical, advancing their subjective

accounts in the realm of visual arts. So, while it was challenging to encounter political tendencies, in some cases, a few artists and galleries still maintain that political engagement by promoting political art. However, these galleries are unable to find commercial success.

Nevertheless, I do not believe that making explicitly political work is redundant. It, too, relates to our existence. Whether apolitical or politically engaged, both are tied to our existence. In terms of questioning my own existence or how all artists consider their existence, art is still political. While criticisms on real-world politics have diminished, in valuing existence, I view that all artists, including myself, have a political message. You are still referred to by some publications as a “rebel artist”. Is this a term you have ever accepted or felt comfortable with?

I had not considered myself a “rebel artist.” However, the repressive political situation in the 70s had stifled me so much that I aspired to liberate myself from it through political art-making. Because that had defined my existence. Is it not obvious to be honest to my existence?

The term “rebel artist” does not satisfy me, but I cannot reject it completely. In fact, the word “rebel” is unfamiliar to me, and I would like to change that word to “resistant.” My resistant political tendency was a barrier to entering commercial galleries. There were hardships because of that, but I never wanted to change that attitude. Discomfort is the driving force of my art. It is because that defines my existence.

Your work has been described as an attempt to question the role of authority possessed by artists, and also by critics. Do you agree with this view, and do you think these power dynamics have shifted since you first began making art?

When I hear the arguments of contemporary artists, I cannot escape the feeling that they have all turned into critics and theorists. I, too, expend a lot of time and effort to produce discourse surrounding my work. I don't negate the significance of criticism and theory; in fact, it is also true that the role of the critic or the theorist has been diminished. The authority and influence over exhibitions is given to many talented curators at museums.

As a result, the roles of critics and theorists have been transferred to the curators, which has shifted power dynamics in their favour. I believe the system of art is being constructed in that direction. Regardless, such transformative tendencies demand critics and theorists to answer serious questions about their method of survival and solution. I don’t think, as the question suggests, that the “power dynamics” have entirely shifted. However, they must revive their earnestness about criticism or theory. Only then, will they discover their path forward and expand the field of criticism or theory. I believe the artist, too, must continue to walk the anxious tightrope between life and art.