Convincing dealers, collectors and other art professionals that the industry needs yet another art fair is no small feat in the 2020s. Nevertheless, that is exactly what the organisers of Photofairs New York have been striving to do during the nearly yearlong run-up to its first edition. Although the early returns leave room for refinement, the fair’s unifying concept and strong management give the new event an opportunity to build a valuable bridge to underserved market constituents at the start of the autumn art season.

Managed by Creo, a joint venture with the international expo organiser Angus Montgomery Arts, the Photofairs brand made its New York debut at the Javits Center on Thursday. The first edition brought together a compact 56 exhibitors whose artists can only do what they do because of the camera’s rise to prominence. Some participating dealers, such as New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery and Los Angeles’s Fahey/Klein Gallery, specialise in high-end classical photography. Others, such as the nomadic Postmasters Gallery and Miami’s Transfer gallery, are best known for championing progressive works in digital media.

“Photography tends to be digested in an art-fair context as one note, and we want it to be a symphony,” says Helen Toomer, the director of Photofairs New York and the former head of the Pulse, Collective Design and IFPDA Fine Art Print fairs (among other credits).

Toomer, in her telling, approaches this venture from a grounding in contemporary art, whereas other constituents approach it from a specific background in photography. But for all sides to engage, they first needed a centrepoint. Nine years after the first Photofairs was held in Shanghai, Toomer and Scott Gray, the chief executive of Creo, believe that their new fair can become that centrepoint in New York.

“The idea for Photofairs is to create space for the medium,” Gray says. “When we launched Shanghai, collecting photos in the Asia Pacific [region] was embryonic. Here, it’s far from that.”

Still, serendipity was needed to bring the event to the US’s art-market capital. According to Gray, Photofairs New York came into being after Alan Steel, the chief executive of the Javits Center, offered the company space in the complex during Armory Week. The one caveat was that leadership at The Armory Show would first need to agree that Photofairs was an ally, not a competitor. Fortunately, Nicole Berry, The Armory Show’s director, immediately lent her support to Toomer and the fair.

The cooperation between the two events has extended beyond intangibles. Photofairs and The Armory Show offer dual-admission tickets granting entry to both fairs on the Friday of their joint run, at a price of $72. (Single-day tickets to Photofairs cost $35, and passes for the full run of the show cost $90.) Toomer also says that Armory Show VIPs are welcome at Photofairs gratis, while Photofairs exhibitors can visit the Armory Show at no cost.

Sales versus exposure

According to Lauren Holowesko Perez, one of the founding directors of Tern gallery in the Bahamian capital of Nassau, the decision to show at the inaugural Photofairs New York was multifaceted. One part owed to efficiency, since the gallery had already been accepted to exhibit at The Armory Show; another came out of appreciation for Toomer, whom Holowesko Perez describes as a “big supporter” of Tern; and a third was about continuing the gallery’s mission to counter what Holowesko Perez calls “the stigma of where we come from. We want to show that there is conceptual contemporary art even in the Caribbean.”

Tern pursues this goal across two stands at Photofairs, each featuring works conceived to counter stereotypical ideas of tropicality. The first displays a not-for-sale installation by Tiffany Smith that offers visitors a moment of respite in what the gallery describes as a “wicker throne chair” surrounded by artificial foliage, soothing light and crystals. The main stand features still photos, digital assemblages and video pieces on Polaroid-size screens by Smith and fellow Caribbean artists Steven Schmid, Rodell Warner and Melissa Alcena. Prices for works in the latter stand range from $1,750 to $4,200.

Holowesko Perez says that the gallery had made “a couple” of sales by the end of preview day. Asked about the clientele at the fair to that point, she said: “I wouldn’t say we’re meeting new collectors in particular—more institutional people.”

Installation view of one of Tern gallery's stands at the 2023 edition of Photofairs New York Courtesy of Tern

Dealers elsewhere at Photofairs echoed Holowesko Perez’s experience regarding transactions on preview day. A director at one veteran gallery shrugged and described sales as “OK” by late Thursday afternoon. The top acquisitions confirmed by a fair spokesperson on Thursday evening were five pieces by Thandiwe Muriu, each priced between $14,000 and $19,000, at Paris’s 193 Gallery. Yet some exhibitors flagged that it is characteristic of photo-based fairs for relatively few deals to close prior to day two at the earliest.

“The medium is still hindered by the perception of editions, multiplicity and reproducibility,” says Douglas Marshall, the founder of Los Angeles-based Marshall Gallery. It can be difficult, he adds, for dealers in this niche to instil a sense of urgency in potential buyers, given that both sides know there are multiple editions of most works available. Contrast this with the automatic scarcity of paintings, drawings and sculptures at fairs, and dealers in lens-based images are largely fated to endure a more leisurely transactional timeline.

The irony in Marshall’s case is that several of his artists produce either unique works or unusually small edition runs. Of the three artists on his stand at the Javits Center, only the sepia-toned photos of Albarrán Cabrera are editioned. The others, by John Brinton Hogan and David Samuel Stern, are one-of-a-kind. Prices across the stand range from $1,500 to $8,000 for a backlit portrait of a Julius Caesar bust woven together from strips of translucent vellum.

“Even today, photography is still a bastard medium,” Marshall says. “My artists tend to be too artsy to appeal to the photographic world and too photographic to appeal to the contemporary-art world. Photofairs fit in that way.”

Marshall also cites the diligence of Photofairs’ leadership as a major incentive for him to take a chance on the brand’s first New York fair. He recounted his experience at an early edition of Photofairs Shanghai, where Gray seemingly never rested in trying to improve the conditions for exhibitors after the venue suffered the aftereffects of a typhoon.

Anton Svyatsky, founder of Management gallery on the Lower East Side, praises Toomer in similar terms. Although visitors to his stand were weighted more towards enthusiasts than collectors on preview day, he says Toomer had personally checked in on him three times by late Friday afternoon, a level of attention he has not received at any other fair.

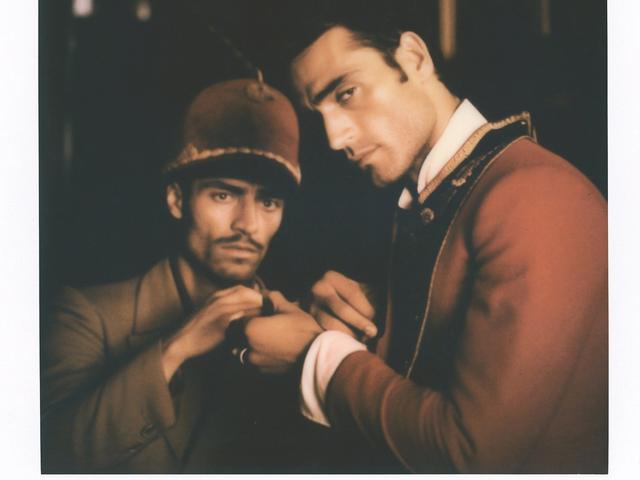

Toomer's actions stood out even more, since Management has only existed for two years and focuses on emerging artists who often defy easy classification. Among them is the subject of its Photofairs stand: Merik Goma, a recipient of Titus Kaphar’s NXTHVN studio fellowship whose images of grieving figures in constructed interiors walk the line between neo-noir and ambiguous fantasy. Available works are priced from $4,000 for a small photograph to $14,000 for a large lightbox diptych.

“We want to make sure people are cared for, meaning the A/C is working, there are places to sit as well as being stimulated by artwork—and acquiring it,” Toomer says.

Modesty and magnetism in new media

Despite Photofairs’ overtures towards bridging photography and new media, the actual results at the first edition are a work in progress. Of the 56 exhibitors and six partner projects at Photofairs New York, 11 stands (about 18% overall) showed moving-image or screen-based works on preview day.

Magda Sawon of Postmasters says of the ratio: “It’s less than I hoped, but it’s still way better than a typical fair with 99% paintings and one Julian Opie.”

For Photofairs, Postmasters curated an ambitious selection of works that charts the medium’s evolution from still photography and video to generative film and pure software. Prices peak at $150,000 for Horror Chase (2002), an infinitely looping, algorithmically edited video installation by Jennifer and Kevin McCoy. But the stand also hosted the most accessibly priced piece in the fair: mononym artist Damjanski’s Bye Bye Camera app, which removes the humans from anything it is used to photograph for just $2.99.

“The fair planned to be an extension of photography into the next stage of image-making. It’s the definition of what we do: present new forms of expression, often through new technology,” says Sawon.

Visitors interact with works by Huntrezz Janos in Transfer gallery's booth at Photofairs New York 2023 Photo: Casey Kelbaugh CKA, courtesy of Photofairs

New forms of expression seemed to be the main draw on preview day. The Postmasters stand was well attended throughout the afternoon, and Sawon reported “very serious enquiries” on multiple pieces. But the unquestioned phenomenon of the fair early on was the work of Huntrezz Janos, who playfully manifested her wishes for a path to a more compassionate and egalitarian understanding of identity.

Examples of Janos's interactive Infilteriterations series are on view at Transfer’s stand at the venue’s rear. Visitors who face the digital cameras mounted atop a trio of human-size LED screens see their actual faces adorned by colourful, multilayered digital filters equally indebted to Saturday-morning cartoons and the masks of ancient warriors or sci-fi fighters. The experience was a hit, as delighted visitors continuously mobbed Transfer’s stand until the end of preview day.

Transfer began the fair offering nine different Infilteriterations priced at $12,000 each, a price that includes the engineering costs of moving the works from Instagram (where they can be freely used by the public via QR codes on one of the stand’s outer walls) to an independent website outside of Meta’s software architecture (where they will remain just as accessible).

The gallery plans to swap out the three works on view at the fair every day, according to Transfer founder Kelani Nichole. Two of the works had already been acquired by the Thoma Foundation, a US-based nonprofit with a robust collection of digitally informed works.

“Opening day has been wonderful. It’s been so gratifying to see people interact and play with the art and one another,” Nichole says. “People’s faces light up when they see Huntrezz Janos’s work. Our booth is filled with laughter and connection. That’s why so many public collections have expressed interest in this work today.”

It will be worth watching which lessons the organisers of Photofairs New York learn from their first experience at the Javits Center. The changes between year one of a fair and year two can be sizable, and both this event and this medium-specific niche of the art trade feel even more open-ended than most.

“We’re excited to grow with the market," says Toomer. "It feels like we’re establishing something that’s needed.”

- Photofairs New York, until 10 September, Javits Center, New York