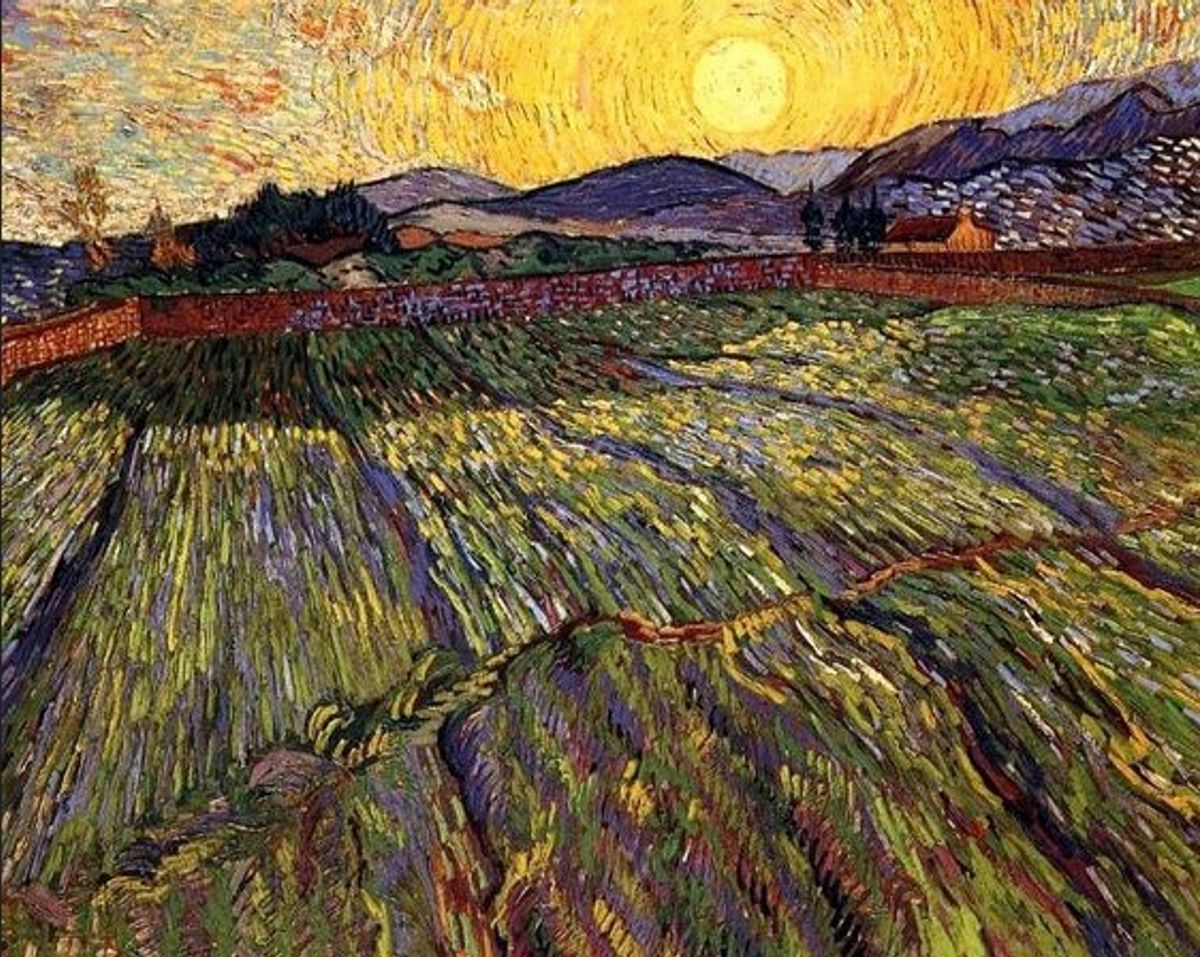

Robert Oppenheimer, “the father of the atomic bomb”, lived with Wheatfield at Sunrise, which he inherited from his parents. Painted in November 1889, it is based on the view from Van Gogh’s bedroom in the asylum just outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence—with the sun rising above Les Alpilles (the little Alps).

Van Gogh wrote about the painting to his artist friend Emile Bernard: “The field is violet and green-yellow. The white sun is surrounded by a large yellow aureole… I have tried to express calm, a great peace.”

One cannot avoid recalling Oppenheimer’s description of the first atomic test, which he masterminded in the New Mexico desert on 16 July 1945: “brighter than a thousand suns”. For Oppenheimer and his scientific colleagues who developed “the bomb”, the ethical question was whether it would finally bring peace—or escalate the Second World War. After the American attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August, the weapons of mass destruction led to the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945, but at an horrific cost: an estimated more than 200,000 lives.

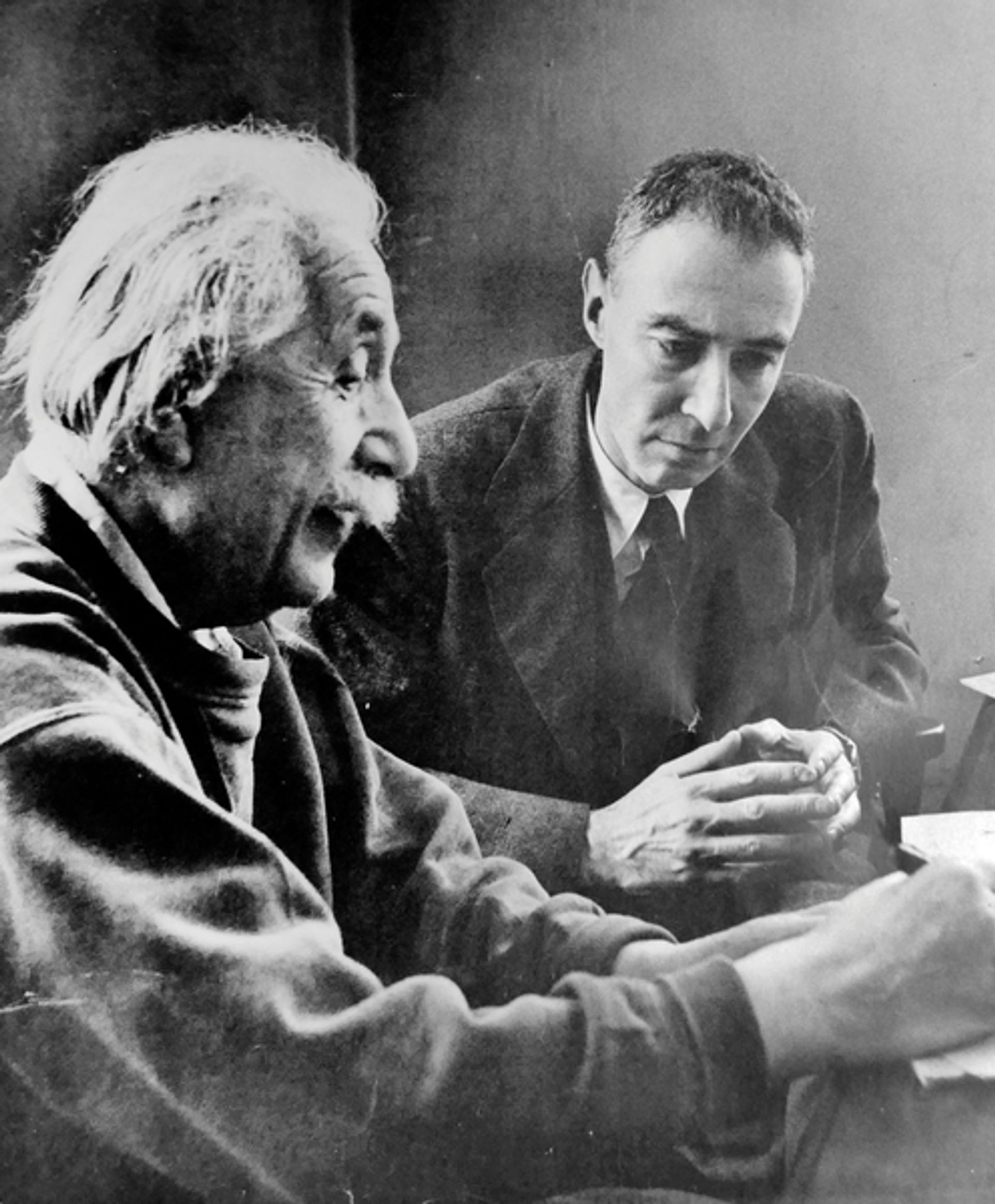

Albert Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer in 1947

Photo: Universal History Archive/UIG / Bridgeman Images

Julius Oppenheimer, Robert’s father, had emigrated from Germany to New York in 1888, arriving penniless. Becoming a cloth importer, he was soon extremely successful and within a few decades he had amassed three Van Goghs. The works were all painted in the last few months of the artist’s life, when he was at the height of his powers. Julius’s wife Ella (née Friedman) was a painter and art teacher, and it was her love for Impressionism and Post-Impressionism which lay behind these acquisitions. She also encouraged the young Robert to paint.

Julius bought Wheatfield at Sunrise in 1929 and a few months later lent it to the inaugural loan exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. After his death in 1937 the Van Gogh passed to his older son Robert, who hung it in his apartment.

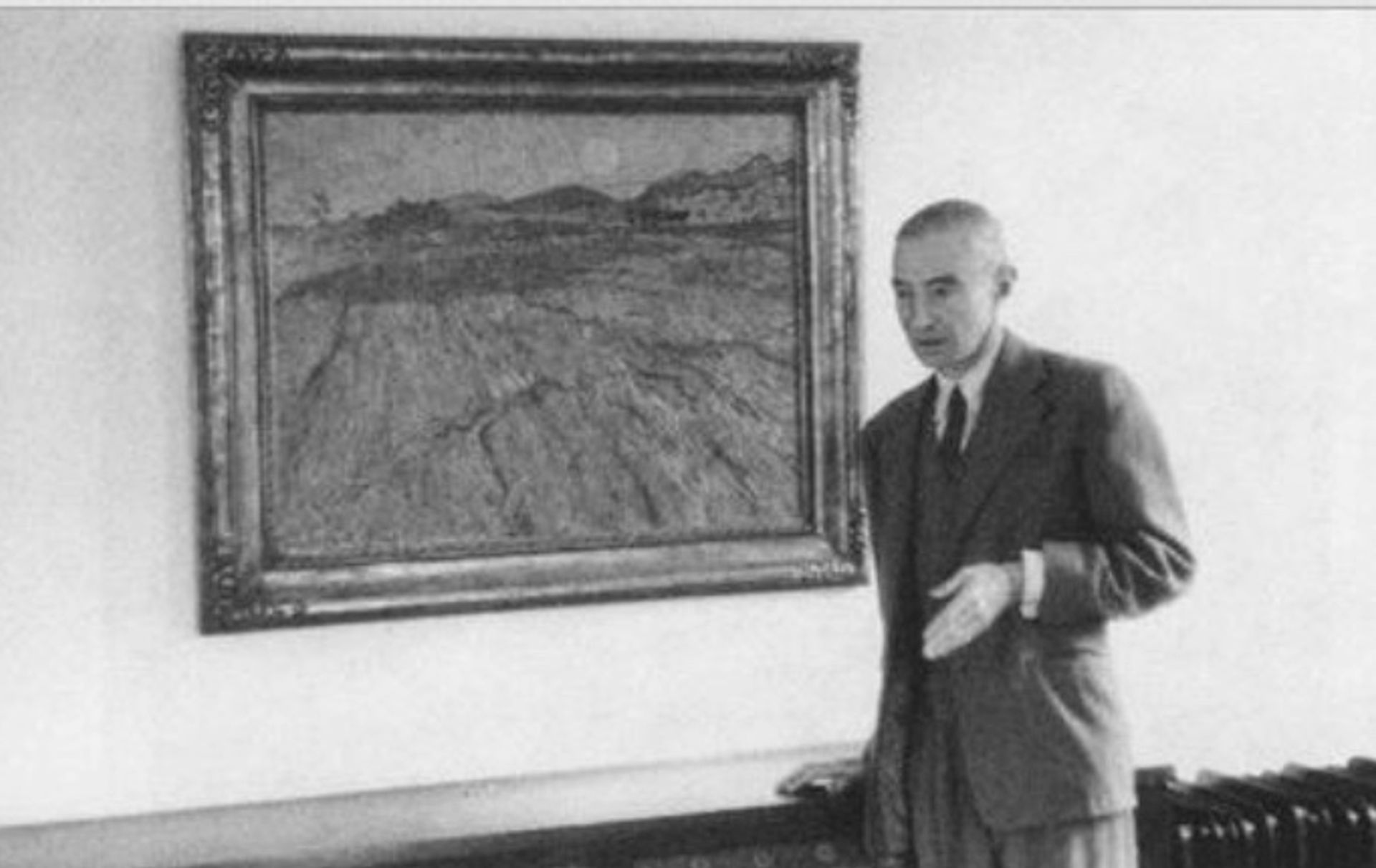

Robert Oppenheimer in 1958 with Van Gogh’s Wheatfield at Sunrise (November 1889)

Robert, born in 1904, had studied physics and joined the atomic bomb project in 1942, leading to the 16 July 1945 test explosion at Los Alamos. He later opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb in 1949, leading to the highly publicised withdrawal of his government security clearance in 1954.

In 1965, two years before Robert died, he sold Wheatfield at Sunrise to the Wildenstein gallery for just under $1m. It was then bought by the flamboyant American writer Florence Gould. She auctioned it at Sotheby’s in 1985, where it fetched nearly $10m, then a record price for a Van Gogh. The painting sold again in around 1990, for a reported $50m, and is now in an unidentified private collection. Today’s value could well be up to $200m.

Oppenheimer’s father also owned two other Van Goghs. First Steps, after Millet (January 1890) is a painted version of a print by the French artist Jean-François Millet, a touching image of a young child learning to walk. Van Gogh made it at the asylum, when he was in fragile health after a mental attack and he was unable to go outside to paint.

Van Gogh’s First Steps, after Millet (January 1890)

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

First Steps, after Millet had been acquired by Julius Oppenheimer in 1926, for $12,900. On his death it passed to his younger son, Frank, who was also a physicist. Frank sold the Van Gogh in the late 1940s. It was donated to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1964.

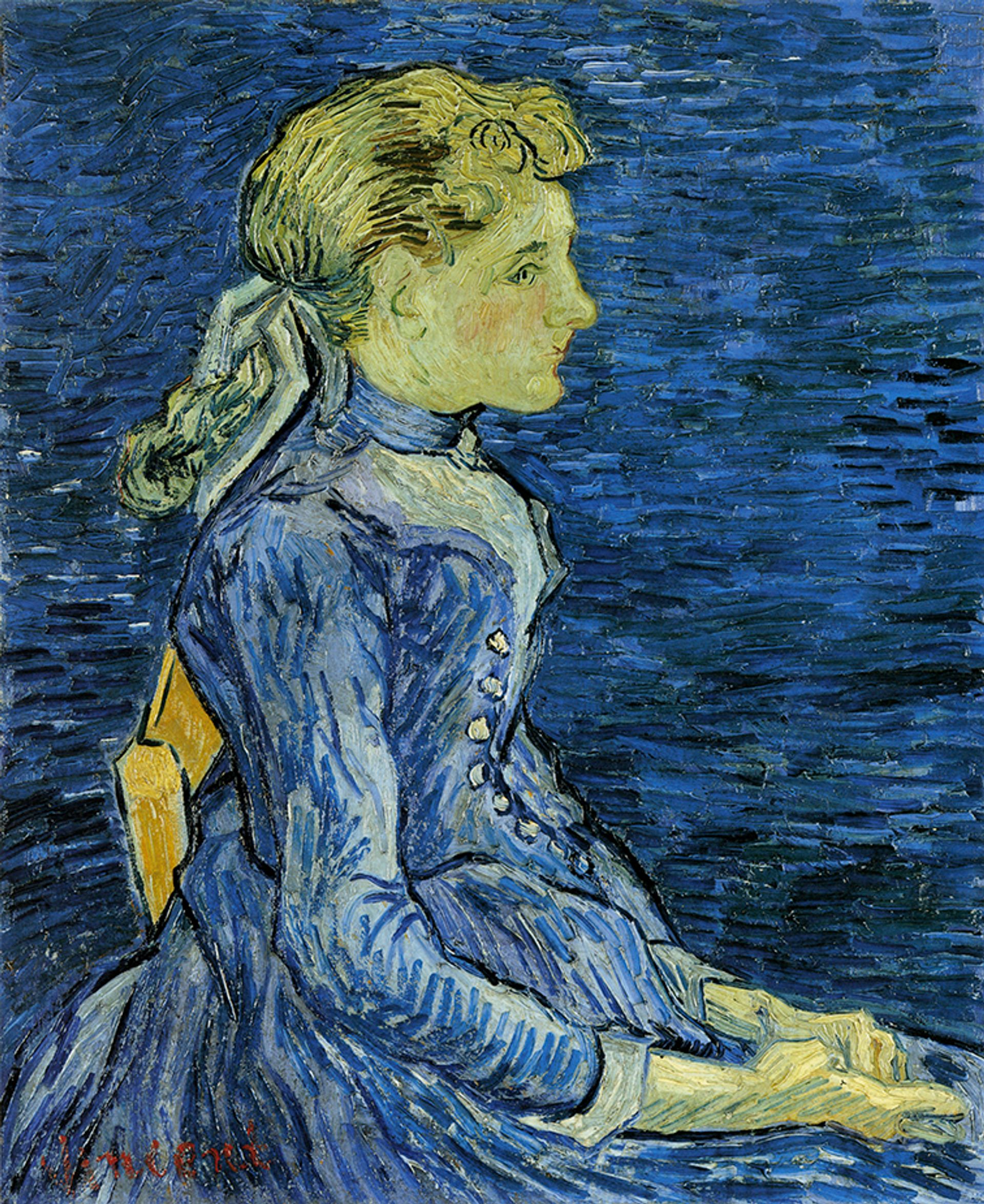

The final Oppenheimer Van Gogh was Adeline Ravoux (June 1890), a portrait of the 12-year-old daughter of the owner of the inn where Van Gogh lodged in Auvers-sur-Oise. It was bought by Julius in 1935 and was later also sold to the Wildenstein gallery. The portrait is now believed to be in a Chinese private collection, sold through the Hong-Kong based company HomeArt. It will shortly be on loan to the Musée d’Orsay for its exhibition Van Gogh à Auvers-sur-Oise: Les derniers mois (3 October-4 February 2024).

Van Gogh, Adeline Ravoux (June 1890)

Photo: private collection, courtesy of HomeArt

Robert Oppenheimer—atomic scientist and also art lover—is now the central character in the highly successful new film Oppenheimer, in which he is played by Cillian Murphy. Although none of his Van Goghs appear on-screen, in one scene he is seen admiring a Picasso: Woman Sitting with Crossed Arms (1937), now at the Musée Picasso in Paris.