In August 1665, the city of Bologna was in mourning. The Church of San Domenico was swathed in black cloth embroidered with gold silk, elegies written for the occasion hung from its columns, and a liturgy, composed by the musical director of the chapel, was sung by the choir of the University of Bologna, after which “sobs and gasps resounded through the Temple”. At the centre of a huge faux-marble catafalque was a life-sized sculpted effigy: a woman at work, seated in the act of painting. “The best brush in Bologna”, the pride of the city, was dead.

So read contemporary accounts of the funeral of “La Sirena”, Elisabetta Sirani (born 1638), a painter of international fame, who, in her lifetime, was Bologna’s most successful artist. Her clients ranged from local fishermen to the Medici and European royalty. Adelina Modesti’s new biography is part of Lund Humphries’s excellent Illuminating Women Artists series, which seeks to restore women to the art history register, and to shed light on incredible and forgotten careers. Few artists need this more than Sirani; as the book unfolds, the question of why becomes increasingly perplexing.

The usual reasons—a lack of archival evidence and extant works, with unsigned works creating issues of provenance—simply do not apply to Sirani. The daughter and apprentice of an art merchant and painter, she meticulously recorded her career, from the young age of 17 to her tragic and still unexplained death ten years later. This ledger was published as part of a biography by her great supporter, Count Malvasia, in 1678 and lists more than 200 paintings—not to mention drawings—of which 149 are extant, alongside 14 collaborative works. Furthermore, around 70% of her works are signed. Sirani must be one of the most documented artists of her era.

Salon studio

Modesti’s sumptuously illustrated book combines this existing documentation with extensive archival research and recourse to new discoveries by scholars active in the field, covering Sirani’s life, career and the world she inhabited as a woman in late 17th-century Bologna. We discover that her studio operated almost like a salon, with accounts describing visitors—particularly the Bolognese noblewomen who were among her earliest patrons—watching Sirani at work, discussing art and literature, or gossiping. Sirani produced portraits and biblical and classical scenes, and she also cultivated her own image via self-portraits (highly prized by her patrons) in which she becomes the Allegory of Painting, Circe, a saint, even using her own face for a painting of Christ.

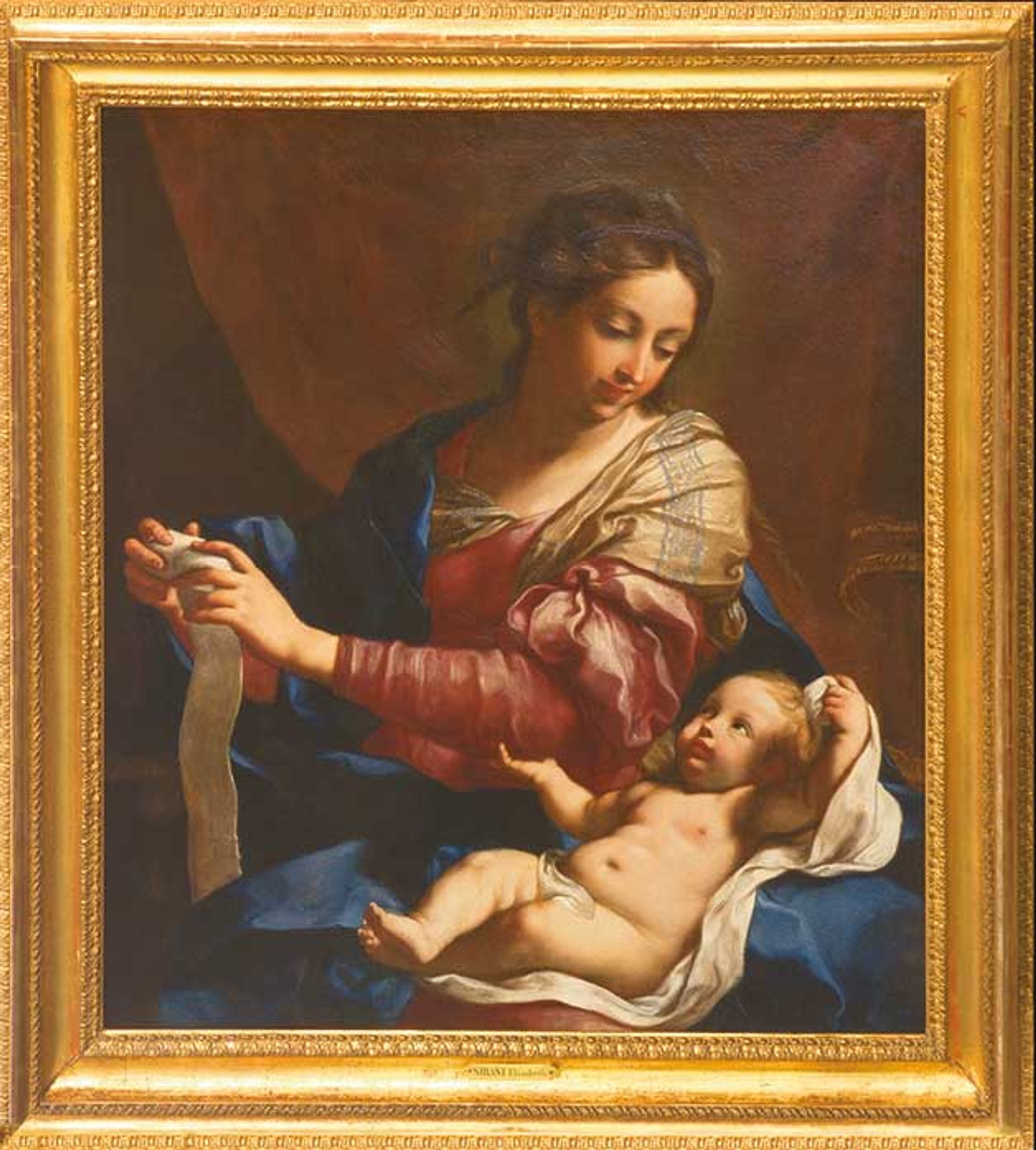

We also learn about Sirani’s method of painting and how, when she was given a commission, she would sweep up a piece of paper and produce a sketch in minutes. Her speciality was paintings of the Madonna, and Modesti presents several images of these works side by side, revealing the artist’s developing style. Sirani wrote that she wanted to “far maniera da se” (make her own way), and she began to explore bold impasto and broad brushstrokes, painted directly onto the canvas. Eventually, Sirani’s style took on a fluidity and ease that differentiated her from contemporaries.

Compared with the rest of Italy—indeed, the rest of Europe—Bologna was a haven for elite women. They were able to study at the city’s university and allowed careers. Sirani herself was highly educated; evidence suggests she read the classics in Latin and Greek, and the records of her reading matter survive in the inventories of the Sirani family library. She emerges here as a fiercely talented artist whose work was intellectually driven. In her Timoclea of Thebes (1659), for example, we see evidence of her classical research. It is a story treated by several artists before her, but Sirani’s version has a twist. Timoclea was a noblewoman who was raped by one of Alexander the Great’s captains during his sack of Thebes. The rapist then demanded Timoclea’s money and jewels, so she led him to a well where she claimed they were hidden. As he peered down, she pushed him into the void and then stoned him to death. She was brought before Alexander for punishment; he recognised Timoclea’s moral integrity and dignity, and she was pardoned. Sirani does not present the rape, or the reprieve, as artists such as Domenichino (a fellow Bolognese) had done. She presented Timoclea in the act of revenge. The scene is straight out of Plutarch, who described her furrowed brow and flared nostrils, her self-possession and fearlessness.

Madonna of the Swaddling (1665); Sirani’s many paintings of Mary demonstrate her developing artistic style

Private collection, Modena; courtesy of the owner

While Bolognese women had more opportunities, they were not treated equally to men. One reason Sirani had kept such a detailed ledger, and signed so much of her work, was to prove her authorship. And it was her father who managed the money. Even so, few female artists before Sirani—and for a long time after her death—were able to run a studio with apprentices and an art school for women. Modesti’s brilliant biography is an important step towards establishing Sirani as one of the most significant artists of her generation: a “resplendent” figure, as stated in her funeral oration, basking in “public praise… applause and universal admiration”.

• Adelina Modesti, Elisabetta Sirani, Lund Humphries, 144pp, 77 colour illustrations, £35 (hb), published 29 June

• Breeze Barrington’s book on women’s artistic production at the court of Mary of Modena will be published by Bloomsbury in 2025