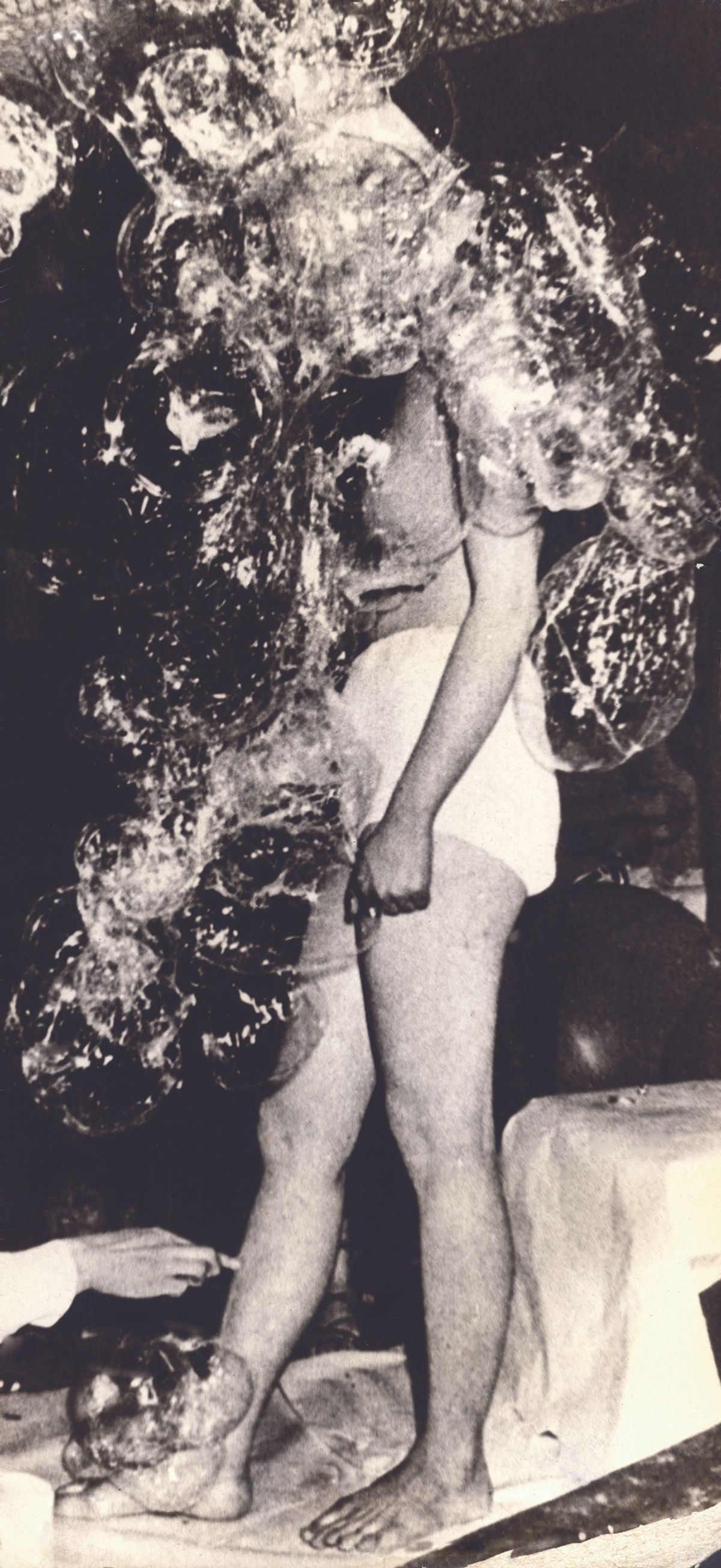

Non-conformity risked imprisonment or worse in the South Korea of 1968, when artist Jung Kangja took to the stage of music café C’est Si Bon clad only in her underwear. With collaborators Kang Kukjin and Chung Chanseung, she invited the audience to attach balloons to her body, then pop them. Intended as a protest against the prohibition on nudity by the conservative art establishment of the time, Transparent Balloons and Nude triggered a broader social outcry.

Performance art happenings like Jung’s—which also included Murder at the Han Riverside (1968), in which she, Kang and Chung were partially buried and drenched before burning slogans on banners—were part of a small but powerful emergence of experimental and feminist Korean art. Female artists like Jung defied the disdain of the patriarchal art establishment as much as scrutiny by the military police under the dictatorship of President Park Chung Hee.

Challenges resonate today

The movement was short-lived but paved the way for an explosion of female conceptual artists in the 1990s and set the stage for the rich diversity of Korean art today. The challenges faced by Jung and her contemporaries resonate for a young generation navigating #MeToo, the Korean opt-out feminist movement 4B, pressures on women to have children in a country with one of the world’s lowest birthrates, and a neo-conservative government with links to the Korean incel movement Ilbe.

“It was not easy for women artists in Korean society of the 1970s,” says Eunju Choi, the director of the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA). While Modernist female artists such as the painter Rhee Seundja (1918-2009) were able to establish themselves within the Korean art scene, paths were harder for experimental figures such as Jung (1942-2017), Kim Soungui (born 1946) and Choi Wookkyung (1940-85).

After Jung married, she was not able to maintain her provocative approach, and moved to Singapore where she juggled raising a family with work, shifting eventually from performance to painting. Kim likewise emigrated to France to study and work with more freedom. In the case of Choi, she embraced Abstract Expressionism while working between the US and Korea, becoming an educator before dying at the age of 45.

Many of these experimental artists featured in a recent exhibition at Seoul’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s, which is now showing at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (until 7 January 2024), then the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (11 February-12 May 2024)

According to Soojung Kang, a senior curator at MMCA and the co-organiser of Only the Young, artists like Jung were among the first Korean women to attend university. “At the time, the patriarchal system forced women into the position of helpers in society and maintained the status quo in the family. However, they resisted established notions through avant-garde experimental art and emerged as a new generation.” Jung’s work “revealed the subjective desires of women, [while her peer] Shim Seonhee showcased the pop culture and trends of the time”.

“Marginal or mad”

By the 1970s the experimental movement was “suppressed by the regime as disturbing and decadent, denounced as sensationalistic, and its activities and stature were long denigrated” in mainstream Korean art history, says Kang. “Experimental female artists were treated as marginal or mad women.”

It was not until the 1990s that women artists become more commonplace in the Korean art scene. A major survey exhibition at Seoul Arts Center, Patjis on Parade—a reference to the archetypal “bad girl” of Korean mythology—was organised in 1999 by a group of women curators and art historians. It provided Korea’s public with an introduction to female artists in Korean art history and the contemporary art scene. Many émigré female artists such as Kim Soungui and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-82), who developed experimental practices abroad, finally became widely known.

Park Young-sook's Imprisoned Body Wandering Spirit #1 (2002)

© the artist and Arario Gallery

Artists remaining in Korea and tackling female topics with experimental media like photography, installation and performance also gained prominence. Lee Bul’s sculptures and installations questioned male authority and the marginalisation of women. Yun Suknam presented experimental installations exploring themes of Korean femininity such as the pressures of motherhood, and photographers including Park Youngsook documented stories of women who rejected conformity to a patriarchal society under the title Crazy Women.

The female artists who emerged in the 1990s “established themselves as artists without distinction between male and female”, says Eunju Choi. “They grew up seeing the reality that older female artists were marginalised in the male-dominated Korean art scene, and they realised that artistic achievement required pursuit as a singular goal.”

In 2019 the MMCA held a solo exhibition of Kim Soungui’s work,

Lazy Clouds, which toured to Germany’s ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe. It was the MMCA’s first major retrospective exhibition of an experimental female artist. As recently as a few years ago, it was rare to find such a showcase of a Korean female artist in Korean museums, but there is a growing move to discover and show lesser-known artists: female artists who were previously written out of Korean art history are finally starting to get their due.

Women still undervalued

“The MMCA exhibition helped to spotlight Korean experimental art in the 1970s, but there is still insufficient focus on female artists. It is high time to discover and exhibit women artists more,” says Sojung Kang, the director of Arario Gallery, which represents Jung Kangja and Kim Soungui. “The main collectors of these experimental women artists have long been Korea’s public museums, but in recent years the scope of collectors has expanded to include private museums and individuals. The current price is about $50,000 to $100,000, which is much lower than that of equivalent male artists. There is a lot of room for their prices to go up,” Kang says, as has been the case for undervalued women artists in the West.

The sculptor Kim Yunshin

At SeMA, says its director Choi, “the curatorial team has a common commitment to discover, exhibit and collect leading female artists in Korea”. She cites a popular 2022 solo exhibition of sculptor Kim Yunshin, who “moved to Argentina in the 1980s and never married, focusing on her art”, but was previously fairly unknown in her homeland. “I think Korean women have a unique strength and grit. And this strength and grit can also be found in Korean women artists.”

Kim Soungui recalls how Art Press ran a long article on her 1973 sea-based installation Situation Plastique III, in Bordeaux, France. “After that, some important Korean male artists invited me to a dinner and during the dinner, one of them told me, ‘As a woman, you do not have to do this kind of experimental work. Anyway, in a few years, you will not continue your work’”, implying she would abandon it for domesticity. “Fifty years have passed now and I’m still doing my work.”

• Choi Wookkyung: A Stranger to Strangers, Kukje Gallery, Busan, until 22 October

• Jung Kangja: Dear Dream, Fantasy and Challenge, Arario Museum in SPACE, Seoul, until 10 September

• Kim Soungui, Bihar Museum Biennale, Patna, India, until 31 December

• Rhee Seundja’s work is at Gallery Hyundai’s stand (M9), Frieze Seoul Masters