The Tokyo-born artist Takashi Murakami has collaborated with major fashion brands, created art for best-selling albums and had exhibitions at some of the biggest museums in the world. But his successful career stems in part from the feeling that he “lacked the talent to do” what some of his anime and manga artist heroes did. Murakami’s distinctive aesthetic is indeed inspired by the work of Japanese artists and film directors like Leiji Matsumoto, Katsuhiro Otomo, Hayao Miyazaki and Hideaki Anno. The latter “did everything I had ever wanted to do”, he says. Murakami studied fine art and the traditional Japanese art form of Nihonga at Tokyo University of the Arts, before moving to New York in the mid-1990s. Western influences on his work include Andy Warhol’s appropriation of popular culture and Anselm Kiefer’s monumentality, as well as the embracing of capitalism by his peers Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst. Recurring characters in Murakami’s work, such as the Mickey Mouse-like Mr DOB and the trippy smiling flowers, have recently been joined by the more sombre “arhat”, based on the wandering figure of an enlightened Buddhist.

Murakami’s latest exhibition, opening this month at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, will include around 75 pieces spanning his career, with a particular emphasis on recent work inspired by the pandemic and the artist’s adoption of NFTs. The show will also bring together his “monster” works, which have their origins in sci-fi and manga as well as a childhood encounter with Francisco Goya’s famously gruesome painting Saturn Devouring His Son (1820-23).

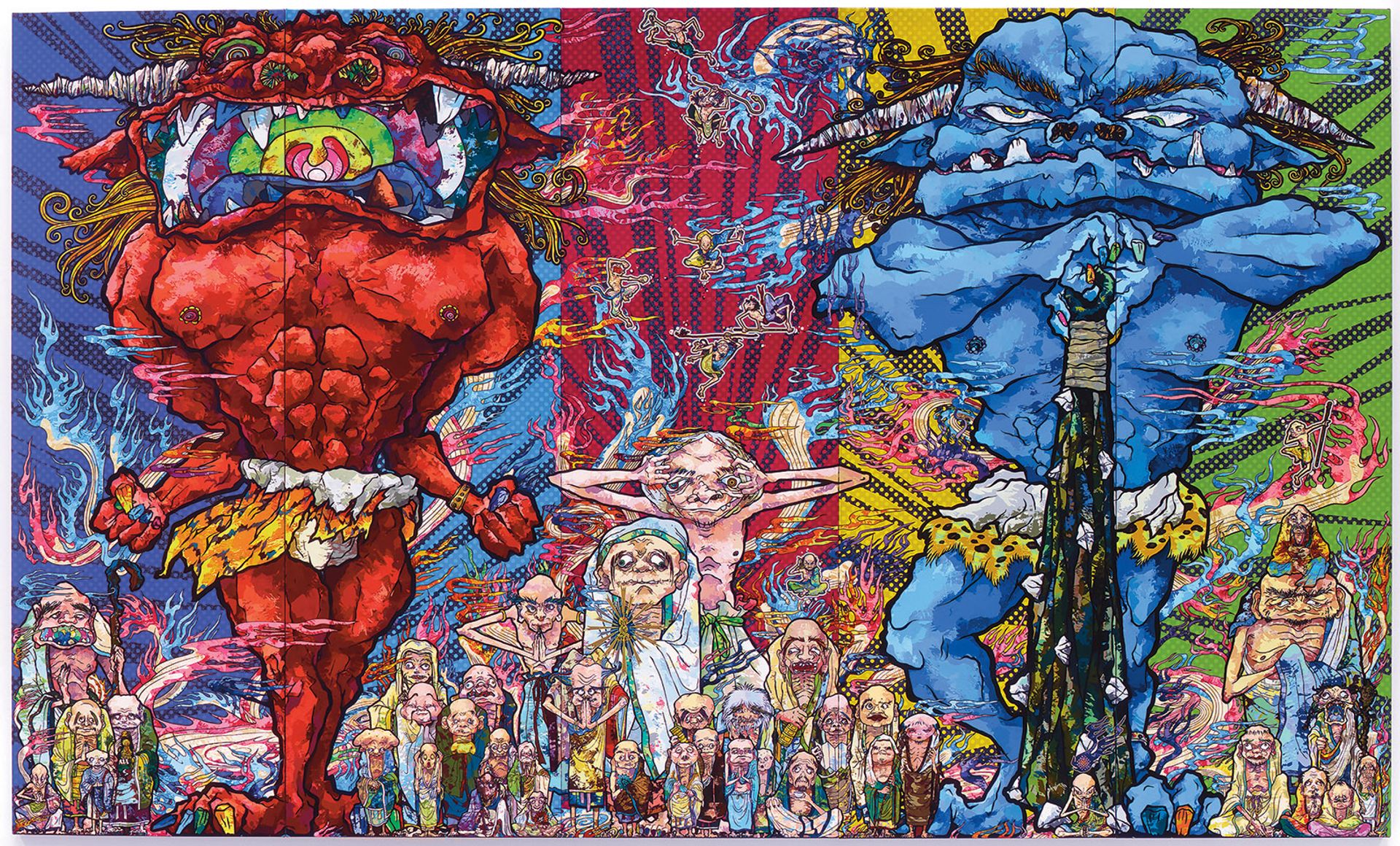

Murakami’s painting Red Demon and Blue Demon with 48 Arhats (2013) combines themes of Buddhist divinity, Edo period printmaking and contemporary Japanese kawaii culture Photo © Phillips Auctioneers; courtesy of the artist and The Heller Group

The Art Newspaper: How did your new show Unfamiliar People—Swelling of Monsterized Human Ego come about? And what does the title refer to?

Takashi Murakami: [The curator] Laura Allen of the San Francisco Asian Art Museum approached me about an exhibition in 2019, and the theme and the title are based on something that came up in my subsequent conversations with her. Once we entered the pandemic, several exhibitions were cancelled and I had some time to spare, so I was able to create a work now titled Unfamiliar People (2020-22), which looks completely different from my previous series. Laura visited my studio five or six times during this period, asking me a lot of questions each time, and we decided to make this work the main focus of the exhibition.

“Unfamiliar people” is a reference to how people changed during the pandemic. Can you expand on this? How did your own work change during this period?

When the pandemic hit, it seemed that people who were until then truly kind suddenly went crazy. I saw how the abuses and trolling on social media got increasingly severe. I learned that, while I used to judge [people] by their appearances and moods, [on] the occasions when I was talking to them in person, the raw humanity in their hearts that became visible through social media was extremely bizarre and absurd. My attempt at visualising this discovery is the painting Unfamiliar People.

Your art also deals with the different artistic hierarchies that exist in both Western and Japanese culture. Can you explain how it plays with and subverts these norms? And how this relates to your “Superflat” theory?

My theory of “Superflat” refers to the Japanese state of being unable to pop up from the devastated, burnt-out and completely scorched land in the aftermath of the utter defeat in the Pacific War—and of having a twisted complex arising out of this sense of flatness. Based on this theoretical background, I am pointing to a state of resignation that, although we are unable to construct a solid history as an independent nation, we can still generate stories that constitute human society by listing the episodes in the daily thoughts and feelings of people who are still alive, and that such narratives do function.

You have collaborated in the past with big fashion brands like Louis Vuitton and Vans, and you also created your own merchandise. At the same time, you have been critical of certain elements of consumer culture and said that you are following in the footsteps of artists like Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons who “battle” capitalism. Can you explain what you mean by this?

Capitalism is not properly installed in Japan. In short, what we have is capitalism within [a] surveillance society unique to Asians, so it is not capitalism that specialises in money amplification. I came to understand the meaning of this, again, after the [2011 Tōhoku] earthquake. And in the way we communicated in the metaverse during the pandemic, it became vividly clear to me.

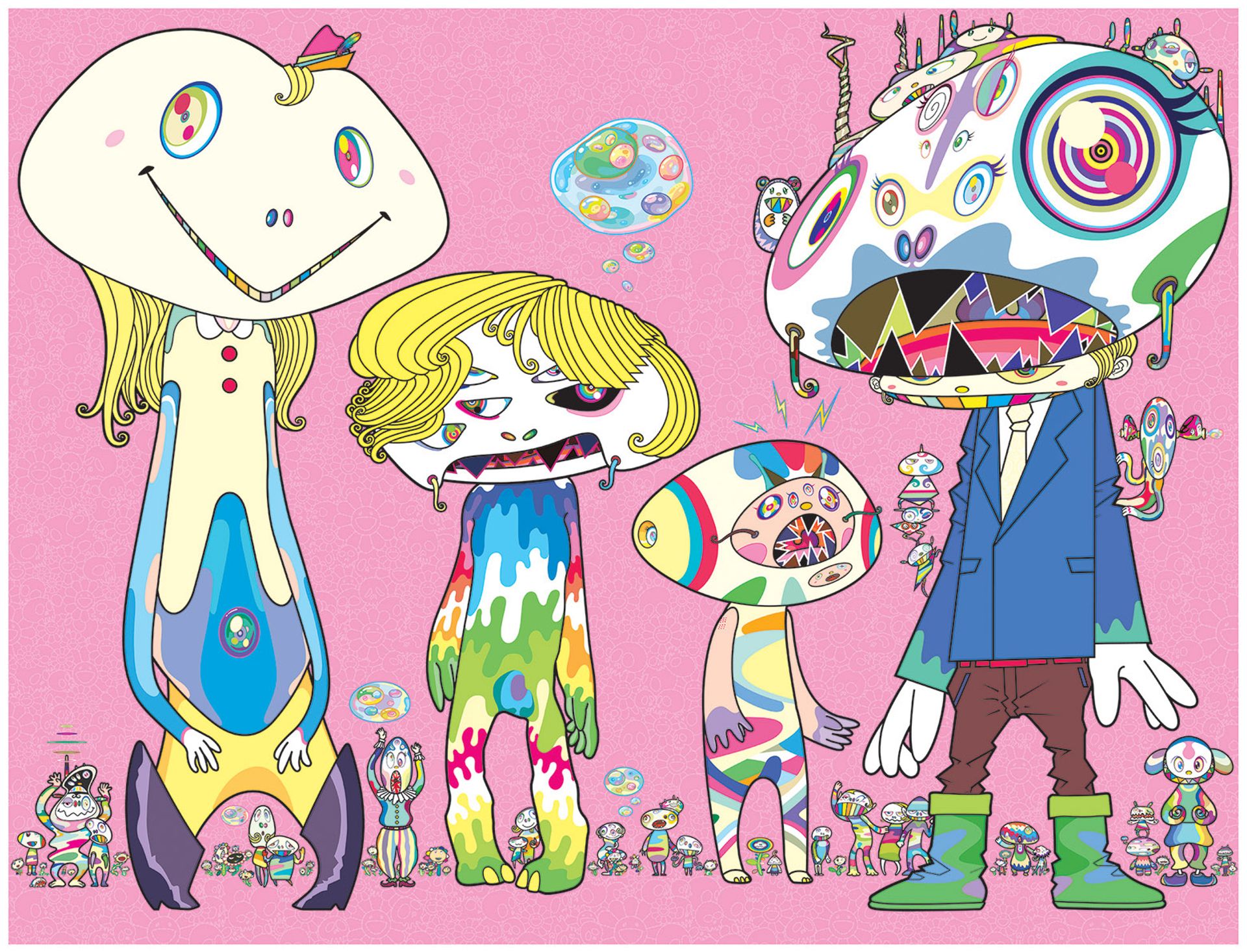

Unfamiliar People (2020-22) is Murakami’s response to how people’s behaviour—especially on social media—changed during the pandemic. It is one of his new works that will feature in the exhibition at the Asian Art Museum 2020–22 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co; Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Art has long existed for the purpose of comforting the socially privileged and financially wealthy. But today, with enough food, clothing and shelter to live at the level of the wealthy 200 years ago, people have more time to spare and need art as a key to solving the great mysteries that have arisen in their hearts. The act of asking the meaning of art has become ordinary. In this sense, I think the chance to be recognised by a large number of people is essential, and collaborating with major companies provides [me] with such an opportunity.

Do you think there is still a snobbishness in the Western art world towards your use of colourful cartoon-like characters and embracing of popular culture?

My merit and demerit in the contemporary art industry may be that I have created a flattened ground or basis on which people can instantly claim their creation to be “art”—so long as it has the appearance of a painting or a sculpture, even if they have no knowledge of the history of art. In that way, I have spread a terrifying custom in the Asian market that, if you follow the format I created—such as painting a design on the sides of a painting panel, or consider it acceptable to repeatedly paint a “hit” motif, or decide the edition structure of a sculpture in a certain way— your work would have the appearance of art.

Art has long existed for the purpose of comforting the privileged and financially wealthy

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in north-eastern Japan had a profound impact on you. Can you explain how the tragedy affected your work?

Until the moment that earthquake hit, I had thought that my field of action was the world of Western contemporary art in the US and Europe, and I was following the lead of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons, who are my contemporaries and whose active conceptual domain dealt with the question: “What kind of relationship should art have with capitalism?” However, the moment I witnessed the natural disasters of March 2011, I instantly understood why Japan is polytheistic and why it worships nature, and why complete Westernisation was impossible for our country.

When [humanity] didn’t have access to the kinds of information that we have today, we were not the protagonists in the natural world. All we could understand was that we were surrounded by things beyond human knowledge, whether they were gods or something else. I thought about the realistic perception of art and religion in the context of natural disasters and the daily environment we live in, and decided to be more faithful to my own reality, which led me to the creation of The 500 Arhats painting [measuring 100m in length] and the subsequent works since.

Having experienced this major turning point has allowed me more recently to find my place in another big moment of transformation: with my NFT works in the metaverse. Although NFTs and cryptocurrencies have recently experienced an extreme decline, young people in their teens and early 20s now have a sense of reality in this [digital] world and, in the next ten to 15 years, they will suddenly and drastically change the ecology of this world. And I have thankfully managed to align with such a movement. In that sense, the earthquake has shifted my main focus away from the relationship between capitalism and art, and as a result I have secured a degree of freedom for my art.

In the past you have likened running a big artist’s studio to working on a movie set, even acknowledging the influence of a behind-the-scenes Star Wars documentary on how you organise your studio. Do you still produce work in this way?

Today, my company Kaikai Kiki has about 220 employees. Thirty years ago, there were no examples of creative studio operations I could reference, so I studied and learned how such a studio should be by watching the making-of videos of Hayao Miyazaki’s [animation company] Studio Ghibli, along with the behind-the-scenes documentaries on Star Wars. I also referred to the making-of videos of [the film director] Peter Jackson’s production of The Lord of the Rings.

Although I had since accumulated expertise in the management of artistic productions over the years, a few months into the pandemic, the company almost collapsed, and I was quite flustered. I realised things weren’t in good order and, from that point on, I have been studying and practicing ways to make the company itself survive.

How has your working process—from initial idea to final piece—changed over the course of your career?

After I moved to New York at the age of 32, I had to produce my work alone by myself, so even when I had complex concepts in my head, I could only execute very simple works, which I felt ashamed of. Now I am able to delegate what I conceive in my head to many staff members and realise the complex thought itself.

Biography

Born: 1962 Tokyo

Lives and works: Saitama, Tokyo and

New York

Education: 1986-93 Tokyo University of the Arts

Key shows:2002 Serpentine Gallery, London; 2007 Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; 2008 Brooklyn Museum, New York; 2009 Guggenheim Bilbao; 2010 Palace of Versailles; 2015 Mori Art Museum, Tokyo; 2017 Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow; Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; Museum of Fine Arts Boston; 2019 Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong

Represented by: Gagosian and Perrotin

• Takashi Murakami: Unfamiliar People—Swelling of Monsterized Human Ego, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, 15 September-12 February 2024