Items belonging to Friedrich Nietzsche and his sister have been displayed for the first time at the Klassik Stiftung in the east German city of Weimar, where the German philosopher died at the age of 55.

Due to his association with German nationalism, Nietzsche was an uncomfortable figure for communist East Germany, so many of the items in the archive were effectively left to rot.

The exhibition Nietzsche Privat (The Private Nietzsche) shows how his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche attempted to create a cult of personality around her brother through art and a “performative manipulation of his archive,” following the examples of famous Weimar writers Goethe and Schiller, according to the curator Sabine Werther.

“When Nietzsche was a healthy, thinking man, there were no paintings of him, only photos. When he became successful he wasn’t aware of this, he wasn’t able to think any more,” so his sister commissioned artists to spread his distinctive image and curate it for posterity, Werther says.

Though Nietzsche was hardly able to speak, let alone write, during his time in Weimar, she set up a desk and when he died his “death room” was modelled after those of Goethe and Schiller, where devotees could touch objects that the philosopher had supposedly used as if they were holy relics. “We want to show the ‘making of’ the cult” Werther says.

Hans Olde, Portrait of Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche (1906)

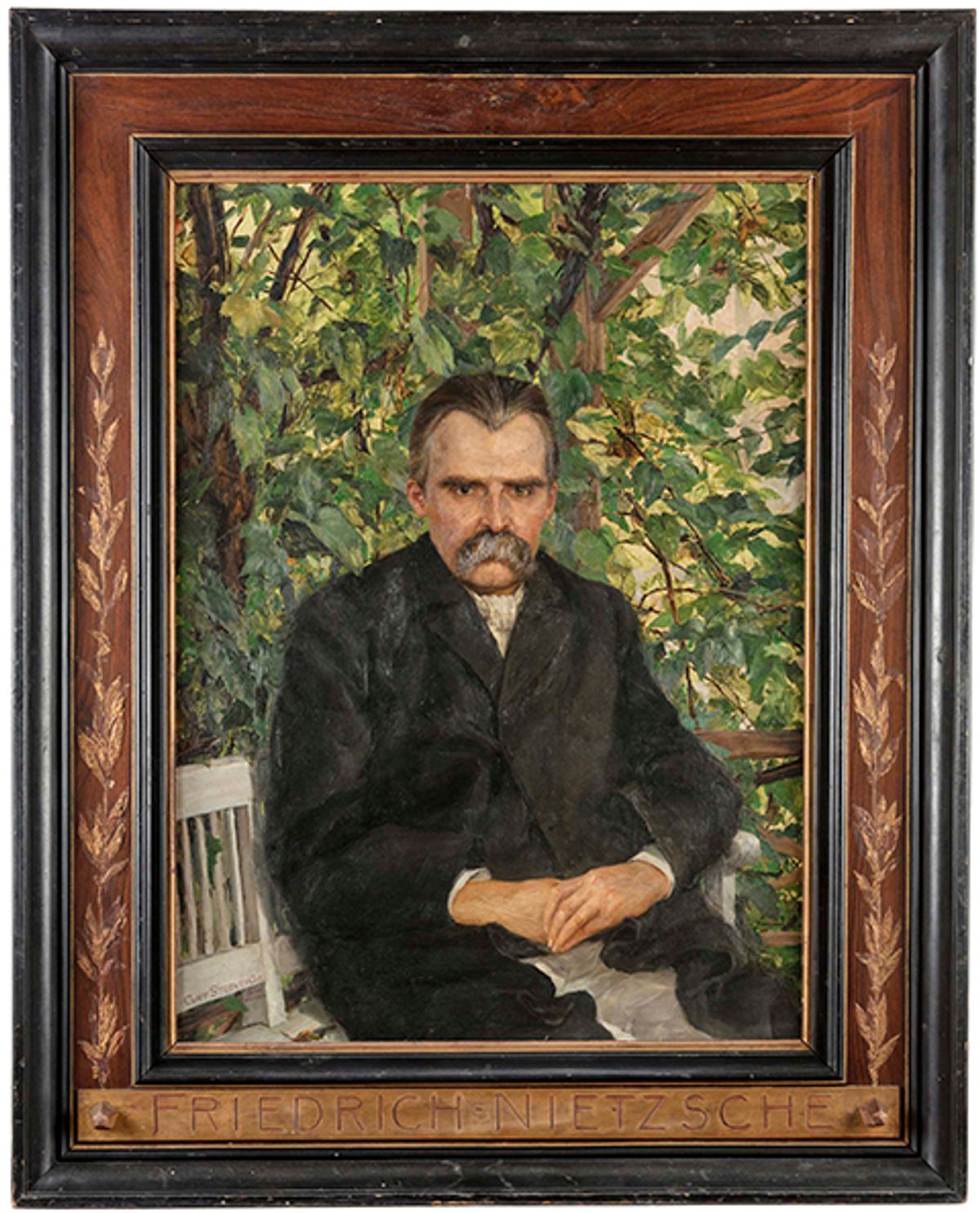

The exhibition includes a number of never-before-displayed paintings from the Nietzsche archive, including the first-ever portrait of the nihilist philosopher by Curt Stoeving in 1894 on oil and canvas, as well as two oil paintings by Hans Olde from 1898 and 1906, whose drawings of the mustachioed thinker are well known and played a significant role in promoting his image.

Olde’s gift of a sketch of Förster-Nietzsche has been restored for the exhibition. This and his oil painting of the view from the Nietzsche archive where he worked was a never-seen before gift he gave to her.

Stoeving’s painting was commissioned by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche for Friedrich’s 50th birthday, shortly after he was released from the Jena mental hospital and went to live in their mother’s house in the small city of Naumberg. Nietzsche suffered a severe mental breakdown at the age of 44.

Hans Olde, View from the Nietzsche Archive (beginning of the 20th century)

The painting depicts a sickly looking Nietzsche in the overgrown pergola in his mother’s garden, clasping his hands together and wearing his white hospital gown underneath a black coat. Though analysis of a template photograph shows “the artist was attempting to soften the obvious signs of the disease” according to the Weimar Klassik Stiftung, the painting did not satisfy Nietzsche’s mother and sister Elisabeth, who were keen to promote his image.

Elisabeth, who was later associated with the Nazis and manipulated her brother’s writings to include antisemitism, had herself just returned from Paraguay, where she had set up a German colony, “Neuva Germania” with her husband Bernard Förster, returning to Germany after his suicide.

A photograph of this painting was published in the PAN magazine, but never displayed publicly before.

The exhibit also includes Being Nietzsche, a virtual reality performance by Judith Rosmair for the Weimar Kunstfest, which shows Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche talking about how to create the “Nietzsche Myth” from her invalid brother’s perspective.