At 76, American artist Maren Hassinger is at last having her day in the sun. Best known for her wire-rope installations and collaborative performances, Hassinger has made a breakthrough in recent years, placing pieces in a host of major American museums, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, and her exhibition schedule is now booked years in advance. Future scholars who want to track the path to her present acclaim—after decades of fostering a much narrower, if passionate cult following—will have to head to Los Angeles’s Getty Research Institute (GRI), which has acquired her archive.

Containing original sketches, drawings for large-scale projects, photographs, correspondence, print media, handwritten notes, documentation of exhibitions and audio-visual material, the archive dates back to the late 1960s, when Hassinger, a Los Angeles native, headed east to Vermont’s Bennington College, hoping to study dance. She later came back west to the University of California in Los Angeles for a graduate art degree, where she discovered the possibilities of metal rope while foraging in local junk yards.

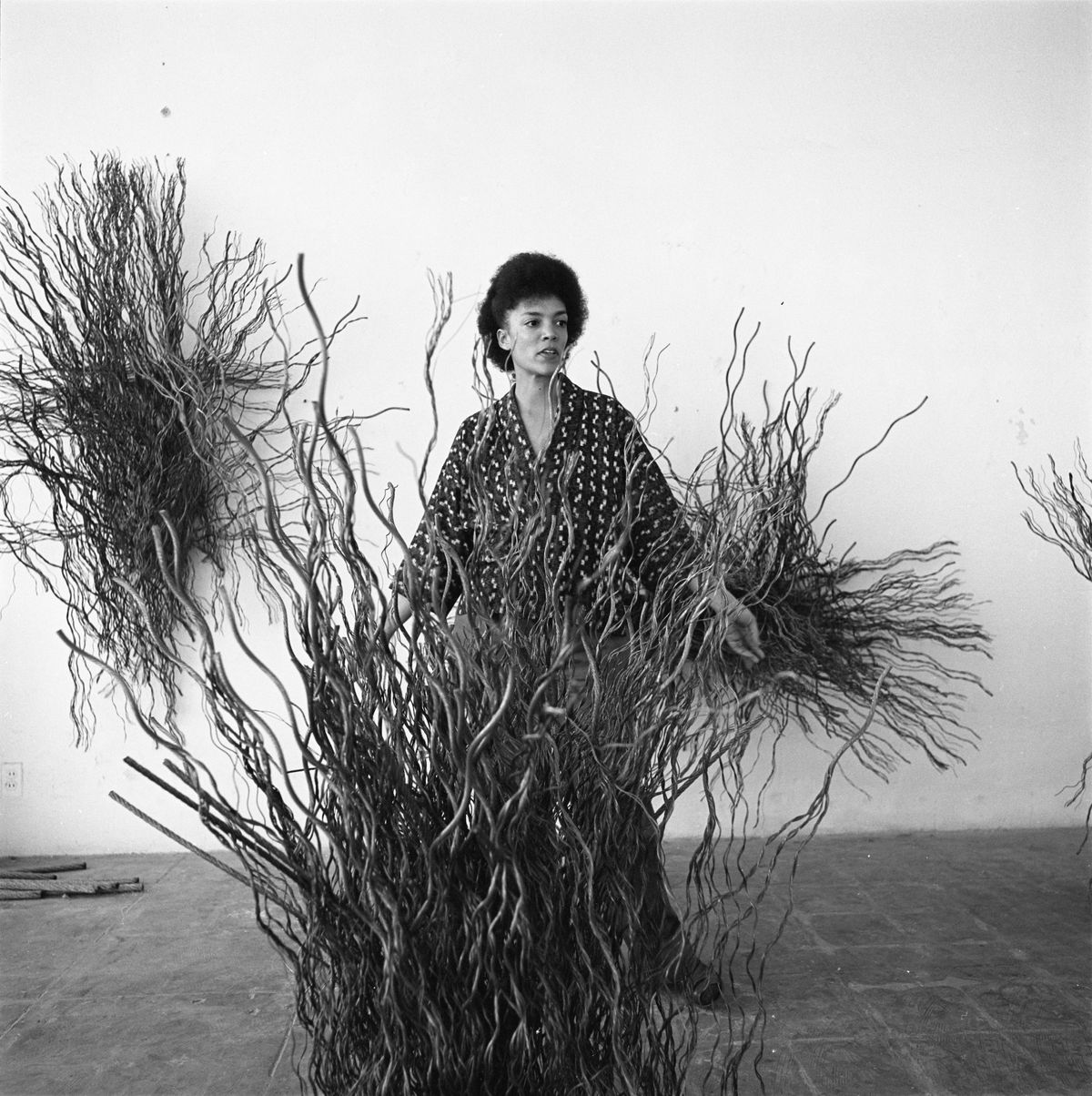

,Maren Hassinger Interlock, 1972. Gift of the Society of Contemporary Art Image courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago

The 1970s were marked by her manifold metal-rope creations, such as 1972’s frayed Interlock, acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago in 2019. The Hassinger archive has been brought to the Getty under the auspices of its African American Art History Initiative. Speaking about the significance of the Hassinger acquisition, GRI’s LeRonn Brooks, who oversees the initiative, says works such as Interlock will be “explicated by the archive”.

Measuring around 200 linear feet, the material is now in the process of being catalogued. After that work is done, Brooks says, it is bound to lead to a newer and deeper understanding of Hassinger’s work, and act as a spur to scholars. “I have no doubt there will be a biography of Maren,” he says.

The acquisition means that Hassinger’s notebooks, a major vehicle in creating final projects, will take their place in the GRI’s holdings, alongside artist notebooks that belonged to the likes of Jacques-Louis David, Diego Rivera and Mark Rothko.

Materials from Maren Hassinger's archive s they were being organised in her previous studio Courtesy the Getty Research Institute

Hassinger’s recent spree of museum showcases and acquisitions, and now the GRI’s enshrinement of her achievement, is a big change, says Jordan Carter, curator and department co-head at New York’s Dia Art Foundation. Until recently, he says, Hassinger was subject to “institutional neglect, like many women and artists of colour emerging in the 1960s and 70s”. But now, “she is getting her due”. Starting in December, Dia Beacon, 90 minutes north of New York City, will present a long-term, newly installed version of Hassinger’s 1983 piece, Field, a vast grid of iron-cable bundles held in place by cement bases.

Hassinger is still busy creating new work—in the last few years, she has been drawn to vessel imagery—and the archive includes materials from all the way up into the 2010s. The sheer span of time can seem to inspire a sense of awe in Brooks. “Archives are the footprint of a life,” he says, adding that a career’s worth of effects is a “kind of bountiful physical memory”.

Maren Hassinger, Field, 1983 Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC

Hassinger can sound more practical. Speaking from her studio in New York’s Harlem neighbourhood, she says she was anything but emotional about giving up the decades-old cache. Largely kept in a basement of her previous apartment building, the archive was more like a collection of stuff. “It looked out of control and crazy,” she says. And when it was finally packed up and removed, she recalls, she thought to herself: “Thank god something is going out of here.”

But when pressed, she also reveals her own sense of awe. The GRI, she says, “really cares about the art and the artist—they take it seriously. So I feel highly honoured to be part of their situation.”