Georgian artists are not often in the spotlight but a new exhibition in Tbilisi will now shine a light on a key overlooked figure and critic of the former Soviet Union.

Levan Chogoshvili's first large-scale solo show in Georgia at the Atinati Cultural Center—a non-profit, charitable foundation created to promote Georgian art and culture—brings together more than 40 works spanning a 50-year-period from oils to his cardboard and paper assemblages along with video pieces. The exhibition (Interling, until 10 July) includes works from three series: Destroyed Aristocracy (1970-1985); Venus and Mar(k)s (1970-1980); andThe Donkey's Way

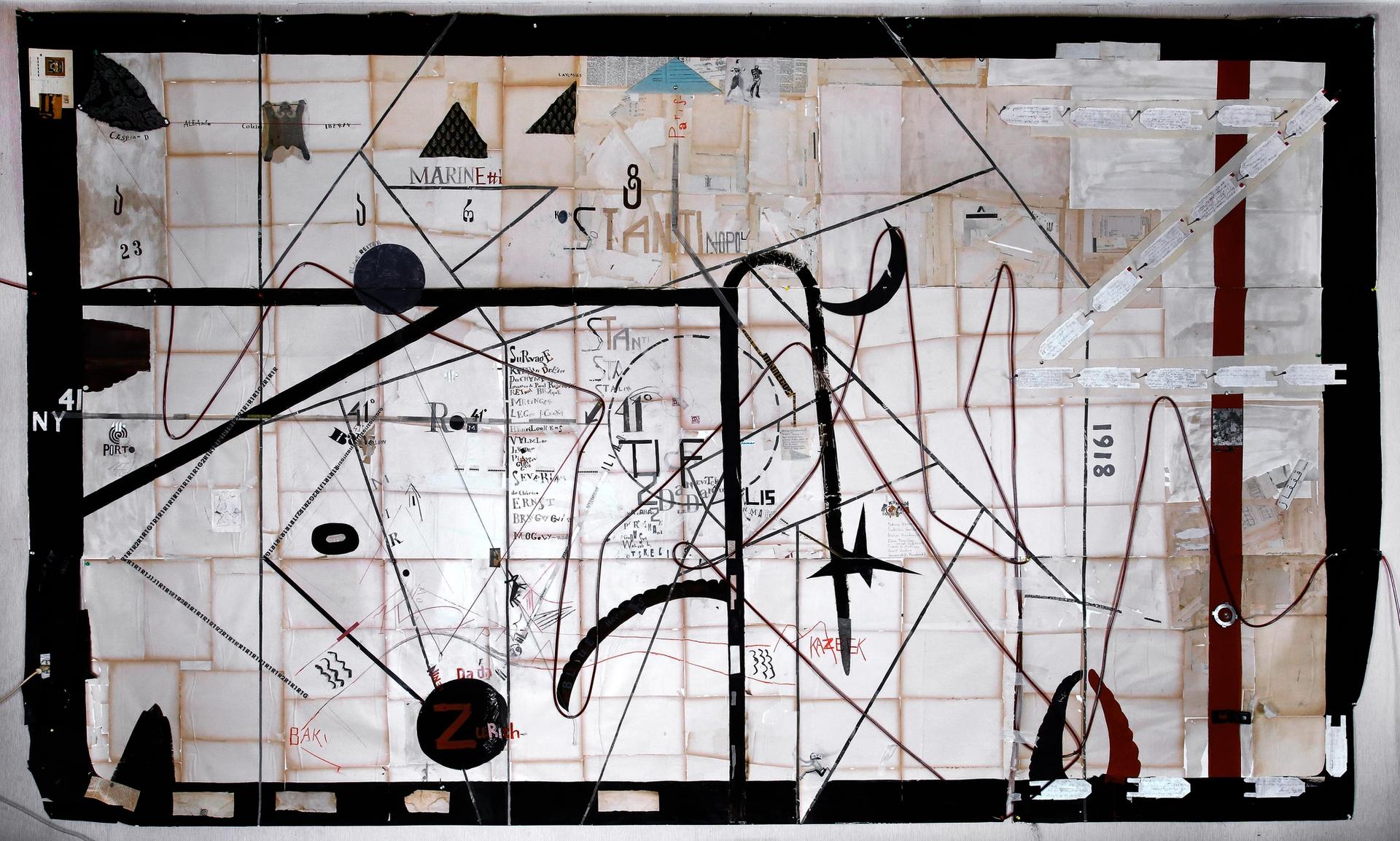

Installation shot of Interling at the Atinati Cultural Center

Courtesy Atinati Cultural Center

In Destroyed Aristocracy, Chogoshvili looks to Georgian church murals and Persian manuscripts, depicting members of Georgian nobility, as well as Georgian and foreign intellectuals—German, Polish, and other nationalities—who settled in Georgia.

In a statement on the Bonhams website, he says: “My painting-from-photography series Destroyed Aristocracy 1970–86, which was banned in Soviet times and which I consider my primary work as an artist, did not arise from a fascination with the tragic events of the beginning of the twentieth century, but rather from an effort to generate a new artistic form via an interpretation of those convoluted historical occurrences.”

Chogoshvili graduated from the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts in the late 1970s, and often featured in underground shows for fear of being censured and prosecuted.

“Before perestroika [reforms introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev, former president of the Soviet Union, in the mid 1980s], Chogoshvili was an ‘unofficial artist’,” says the exhibition curator Nino Tchogoshvili, professor in art history at the Tbilisi Academy of Art.

“During his studies in the 1970s and in the first half of the 1980s, [Levan] had no opportunity to participate in official exhibitions. His art was against Soviet policy, cultural policy in content, in form conceptually, so his first exhibition had great resonance. Such critical works were impossible in Soviet art, but this exhibition was in 1985 when censorship was no longer so strong," Tchogoshvili says.

“After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Chogoshvili became ‘unofficial’ again in the 1990s because he could not cooperate with the government, which led to ten years of terror in the country during a time of wars, hunger and poverty. He created video works and performances criticising the post-Soviet period [and regime].”

Levan Chogoshvili's Untitled Panorama

Courtesy the artist

The word “Interling” is a play on words linked to projects that were unrealised in the 1990s because of censorship at that time, she says. It also highlights the linguistic aspect in Chogoshvili’s practice. His father, George Chogoshvili, was a renowned mathematician and worked on a six-language dictionary while his mother Msia Andronikashvili, wrote key texts on the relationship between the Indo-European and Georgian languages.

In the 1990s, when there was little in the way of paper, electricity, heating or money in Georgia, scientists and artists used whatever they could, such as tea bag paper and toilet paper, for their work, Tchogoshvili adds. At that time, Levan Chogoshvili, together with his brother Archil, was engaged in linguistic experiments, which had their roots in the Georgian avant-garde of 1910, reflected in the work Zaum by Ilya Zdanevich and the poets’ group Blue Horns.

In the early 2000s, the artist won the Pollock-Krasner Prize. Chogoshvili has participated in exhibitions curated by Daniel Baumann including a show at Kunsthalle Zurich in 2018. He is currently working on an exhibition dedicated to the Georgian avant-garde scheduled for October as part of the Europalia festival in Brussels.