In 1809, William Blake wrote in the catalogue to his one-man exhibition: “Tell me the Acts, O historian, and leave me to reason upon them as I please; away with your reasoning and your rubbish.” Susan Owens’s bewitching new book has few certifiable acts, and a good deal of reasoning and rubbish.

A former curator of paintings at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, Owens’s previous publications include a cultural history of ghosts. This time she tracks the half or wholly invented histories that people have chosen to be haunted by, turning their backs on the dull or terrifying facts of their own day.

The Victorian architects who built suburban villas resembling medieval monasteries were careful to include gas ... and bathrooms

This yearning for England’s good old days has very long roots. Owens writes beautifully of confronting the tattered manuscript of Beowulf, thousand-year-old sheets of vellum recording a story already centuries old, and noting “what makes me catch my breath is a single word on its second line”. The word is “geardagum”, the days of old.

Often believers can only keep the faith by consciously holding the truth at bay. The Victorian architects who built suburban villas resembling medieval monasteries were careful to include gas, electricity—and bathrooms. In the decades before and after the First World War, there was a renewed surge of interest in the supposed honeyed days of fast-vanishing rural England, a craving for a lost Arcadia that began in the late 18th century with mechanisation and the shuffle towards industrialised cities. William Cobbett, a farmer, recorded the frequent reality of rural squalor and poverty in his early-19th-century Rural Rides. And yet, as Owens records, he chose to buy a long oak kitchen table, to save it from being bought by “some stock-jobber” to become a bridge over “an artificial river in his cockney garden”. George Sturt, a champion of disappearing rural crafts, admitted in his 1912 book Change in the Village: “The want of proper sanitation for instance; the ever-recurring scarcity of water; the plentiful signs of squalid and disordered living—how unpleasant they must have been!”

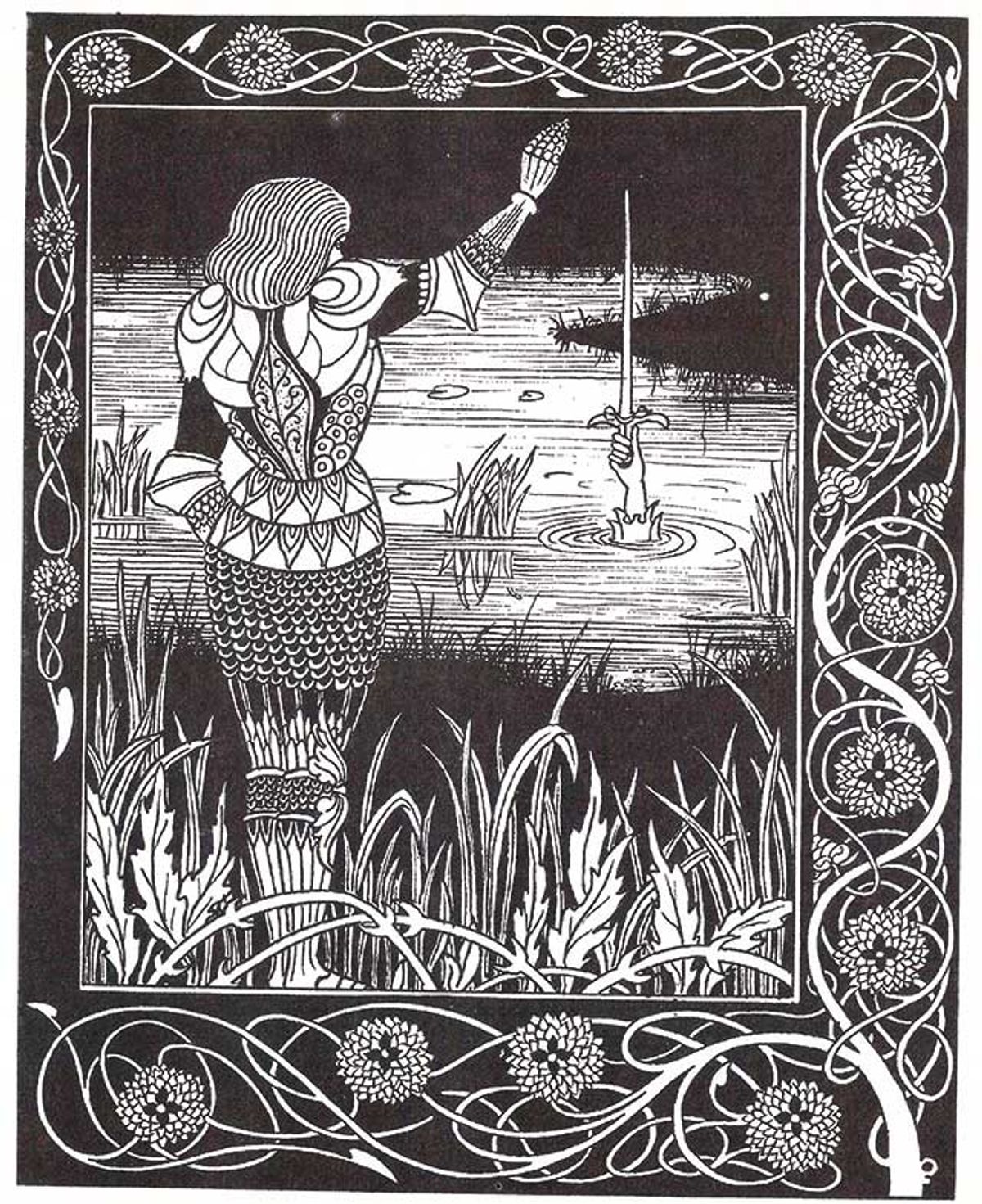

The legend of King Arthur

King Arthur Uther Pendragon refuses to stay asleep under his hill but wanders in and out of Owens’s narrative, his legends obsessing medieval kings and laudanum-hazed 19th-century artists and poets alike. Owen scrupulously knocks down the myths, noting “the small but inconvenient fact” that Gildas, the only conceivably contemporary historian, writes about Bladon, the battle that was supposedly Arthur’s greatest victory, but never mentions the king. She tracks the rolling snowball accretions to the tales that transformed Arthur from a Dark Ages warlord into a king of noble chivalry, gradually bringing in the whole Camelot crew of wizards and enchantresses, shining knights and glittering ladies who, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, writing in the 12th century, “spurned the love of any man who had not proved himself three times in battle”. Perhaps the most beautiful knitting together of the tales was Thomas Malory’s 15th-century Le Morte d’Arthur—beloved of generations of writers, including my father, who wove chunks of it into one of his own short stories. Malory, Owens notes, had good reason to be nostalgic about the olden days, since he wrote most of the book while a prisoner for an assortment of offences including rape, murder and/or treason.

And yet, Owens can’t quite expel Arthur. When the monks of Glastonbury needed a five-star pilgrimage attraction in 1191, they very conveniently found a great coffin made from the trunk of an oak tree, containing the skeletons of a man and a woman. Even more conveniently it was labelled with a lead cross inscribed in suitably wonky “ancient” lettering, “here lies buried the renowned King Arthur on the Isle of Avalon”, making the other skeleton Guinevere, obviously. The crowds came.

Clearly an outrageous invention. But, she wonders, is this lie actually so cut and dried? Would 12th-century monks have faked Arthur in a hollowed-out tree trunk rather than a noble vault and a stone effigy? Would they have known to use an archaic sub-Roman script for the inscription? “As with other aspects of Arthur’s life and death, a lingering suggestion of uncanniness cannot quite be dispelled,” Owens observes. “Never mind, Arthur may never have lived, but he certainly shows no sign of dying.”

• Maev Kennedy is an arts and archaeology journalist and regular contributor to The Art Newspaper

• Susan Owens, Imagining England’s Past: Inspiration, Enchantment, Obsession, Thames & Hudson, 320pp, 96 illustrations, £25 (hb), published 13 April