When Grayson Perry stepped up to accept the Turner Prize in 2003, he famously declared, with characteristic irony, that it was high time the award went to “a transvestite potter from Essex”. Now, ceramics are commonplace throughout the art world and his ornate vessels and plates—their surfaces often adorned with coruscating social comment and snipes at the art world—along with more recent forays into tapestry, prints and sculptures as well as his ever more elaborate outfits, have won Perry a high public profile and numerous more accolades. He was elected a Royal Academician in 2012, was the first visual artist to deliver the BBC’s prestigious Reith Lectures in 2013 and won the Erasmus Prize in 2021. Already the recipient of a CBE award, this year he received a knighthood for services to the arts. Perry also has a high public profile for making and presenting award-winning television documentaries on subjects such as masculinity, identity, taste and Englishness, while his Grayson’s Art Club television series attracted huge audiences during the Covid-19 pandemic. He has had retrospective exhibitions over the years in Amsterdam, Oslo and Australia, and this summer the National Galleries of Scotland has organised Perry's first major UK retrospective exhibition—and the largest ever of his work—which opens at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh.

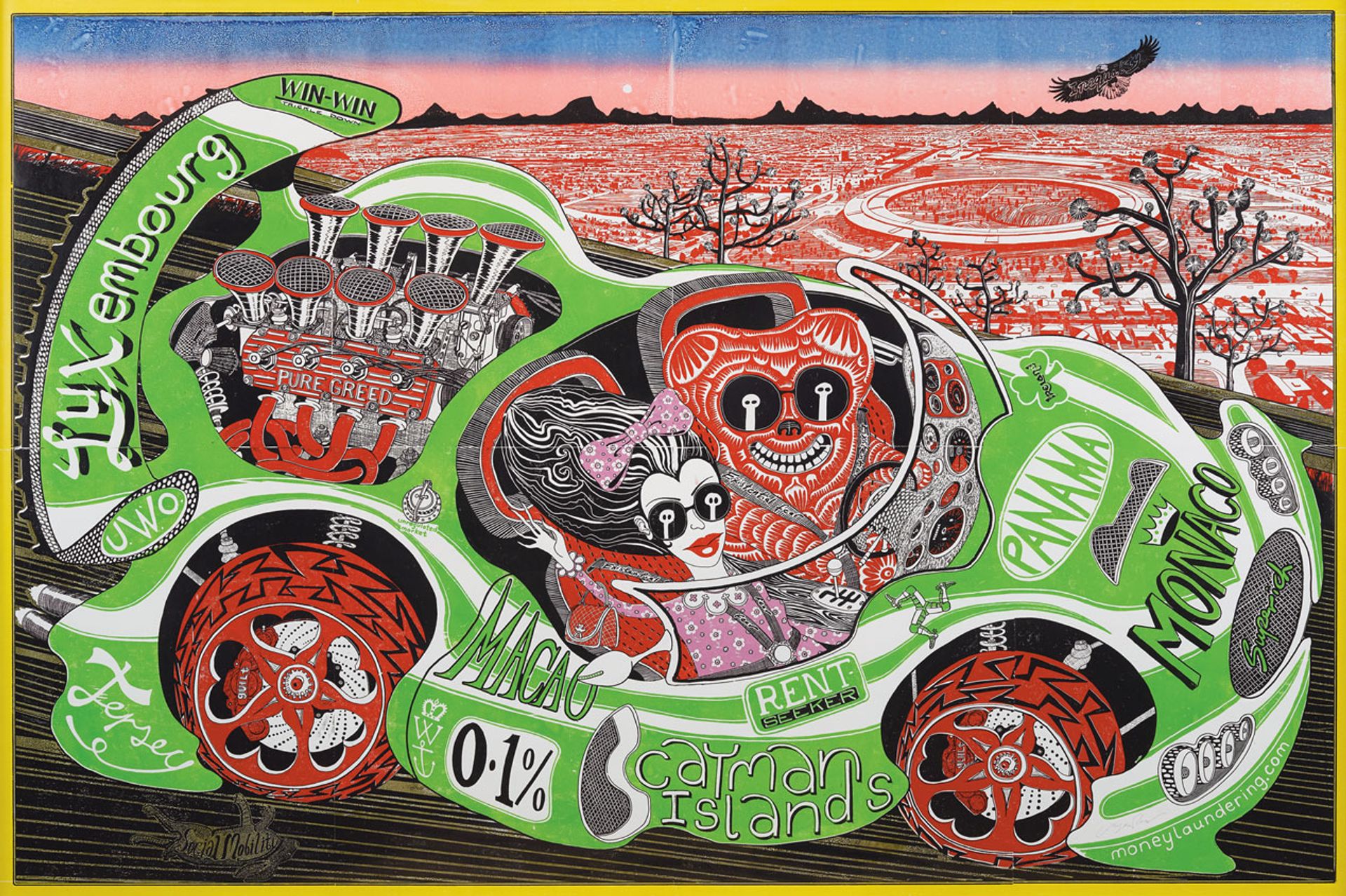

Grayson Perry's woodblock print Sponsored by You (2019) © Grayson Perry.; Courtesy the artist; Paragon. Contemporary Editions Ltd and Victoria Miro; Photo: Jack Hems

The Art Newspaper: The show spans your career, from your first work, a 1983 ceramic plate called Kinky Sex, to the most recent, Sir Pervert, made this year. Is the latter a comment on your recent knighthood?

Grayson Perry: I made a riposte to that first work because as I collect yet another accolade, I always think: have they actually looked at my work? One of my great tactical triumphs has been that, from that very first plate, I led with my secret. All my early work was about my various perversions and lusts and cross-dressing and everything. It was there from the centre. And every time I’m welcomed into yet another higher echelon of the establishment I just think, yeah, it worked!

Did you ever consider refusing this ultimate establishment acknowledgment?

No! When I got the CBE, which was about 10 years ago, I remember saying to [my daughter] Flo, do you think I should accept it? And she said, “Don’t be so affected, that’s not you, Dad.” I scanned my own reactions to it, and I found it amusing. With the knighthood, I only ever use it on texts to my closest friends. I just sign off, Sir G. But I’d never use it in any other context whatsoever. I’m going to pick it up in a few weeks’ time.

As I collect yet another accolade, I always think: have they actually looked at my work?

What are you going to wear?

I’ve been designing madly. My reference points are Carolean. I thought, let’s reference a previous [King] Charles. So I’ve gone back to that period of women’s dress: big, taffeta-billowy and quite matronly, because I have a matronly figure now.

As well as winning the Turner Prize, the Erasmus Prize and being elected a Royal Academician, you have also won several television awards. Do you feel that your success as a TV presenter has affected your art-world reputation?

I called my Serpentine Gallery show The Most Popular Art Exhibition Ever! because of that. I will always taunt that idea of exclusivity and the desperate need of the art world to hide behind performative seriousness. One of my great campaigns is about accessibility, but not in some kind of community, huggy kind of way. There’s some great art and you don’t need an MA to understand it. This weird idea that you have to use a certain vocabulary to appear like an adult in the art world; it’s pompous, pretentious and undignified. I think you can be just as powerful and complex and use accessible language and talk in accessible terms. Often, I think the art world gives too much power to writers—he says to a writer!

Cocktail Party (1989): while Perry made his name as a ceramicist, now, he says, “I probably spend a third of the time making pots”

© Grayson Perry. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Has making and presenting television programmes had an impact on the kind of art you make?

My TV stuff took me into making work more outside of myself because up until 2000, when I had therapy, I think my work was really self-absorbed and it was all about me. Then I really just gorged on it doing therapy and it gave me permission to say ‘OK, now I’m going make work about class and society’. And so although all my work is self-portraiture to a certain extent, now it’s also about other things. I look at my early work now and it does seem a little bit obscurantist and self-obsessed. But I think that’s true of any young person, so I’m quite compassionate towards it. It’s a young person’s art.

Is clay still your core medium? Lately, you seem to have diversified into textiles, metal sculpture, prints.

If I think about the last ten things I made, maybe half of them were pots. But in terms of man hours in the year, I probably spend a third of the time making pots. But then I also do sculptures, which tend to start with ceramic; if I make a bronze I start it with ceramic because that’s the material I know how to work with. But tapestries and prints are also important to me. For my next show at the Wallace Collection, in a couple of years’ time, I’m doing a tiled cabinet and I’ll also probably do a carpet.

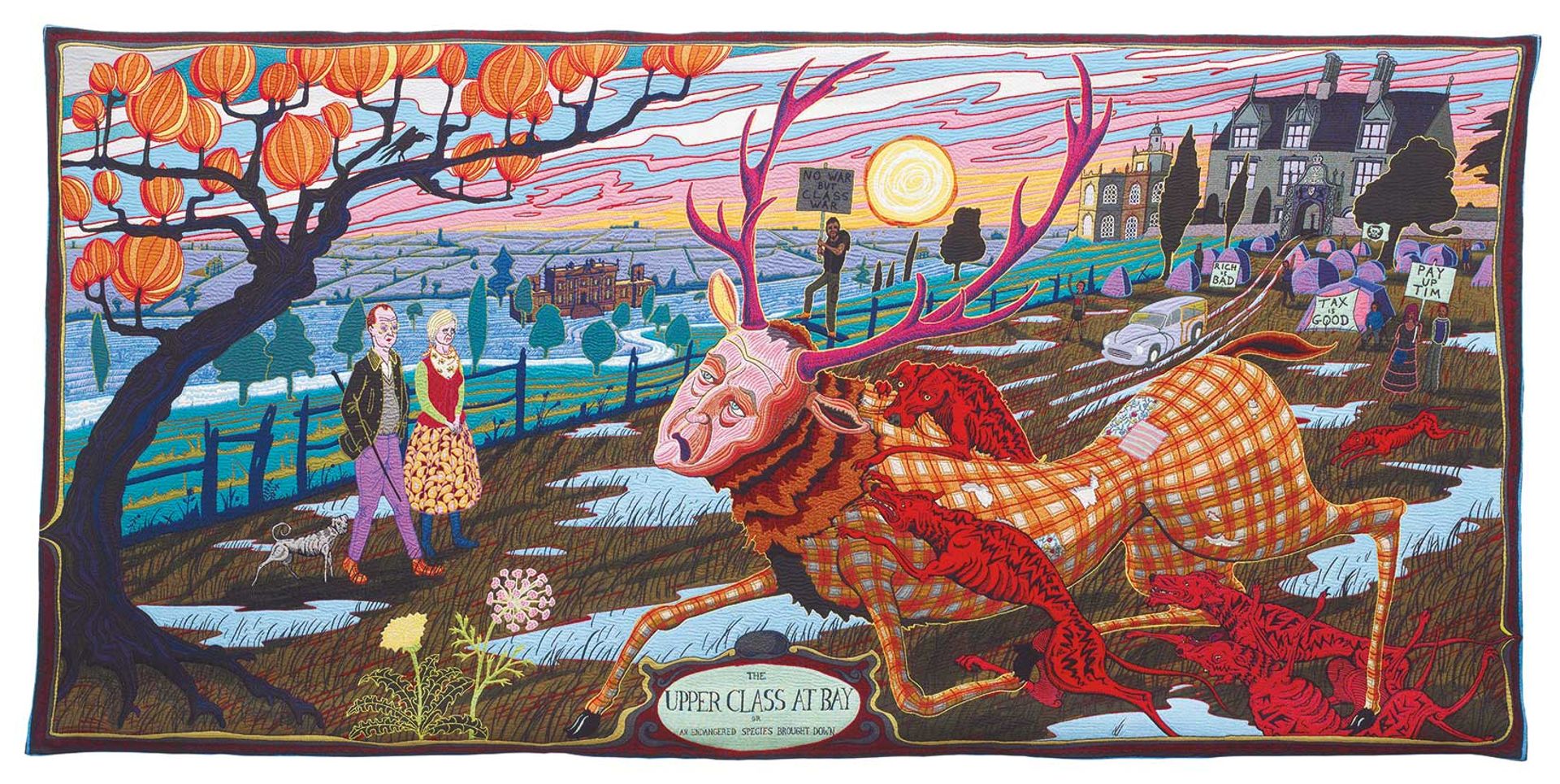

In the tapestry The Upper Class at Bay (2012), a “new-money” couple—inspired by Thomas Gainsborough’s portrait, Mr and Mrs Andrews (around 1750)—survey a stag representing the dying, land-owning breed

© Grayson Perry. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Even though your tapestries are machine made, I still see you as very much a maker.

Totally. It’s about the relationship with craft and materials and the covetability of the object. I use it as a platform also to critique conceptual art, in that if I want to do performance, I’ll do it in the fucking Albert Hall, mate! I’m not going to do bad theatre in the back room of an art gallery. And if I’m going to do TV, I’m not going to make a boring 28-minute video that’s badly edited and show it in a white box where you have to sit on an uncomfortable bench; I’m going to make it for the people sitting at home on their sofas on Channel 4. This is very much what I’ve always done. When I started making pots, I didn’t make ceramic sculptures, I made pots. And when I do a print, I want it to look like a map or something we all know already, where the actual genre is not up for grabs. Singing is my latest thing: I’m making a musical. It’s going to be dead traditional. I’ve been working on it for three years with Richard Thomas, who did Jerry Springer: the Opera.

What’s the subject of your musical?

We’re making Grayson Perry: the Musical. It’s my life as a musical, but heavily fictionalised so we could make a good, fun story. And we’ve written 14 or 15 songs already. I think it’s going to open in Birmingham in 2025.

What is it that makes you want to try out new things all the time? Most people would be quite happy just to be a successful artist.

I love learning. There’s a real energy in that for me; it’s just the novelty of it. Singing is a perfect example. I started just before lockdown, and it was really hard at the beginning. Then you reach a little platform and it’s like, ‘Oh, I can do this now!’ And then you reach another little platform and it’s exciting. It’s a whole new world and you’re learning all the time. It’s the same with the musical: when we started I was reading books about how you write a musical and the history of musicals and gossip about musicals, and I was going to see musicals because I just love learning about stuff—it’s so enthusing.

Perry drove the colourful Kenilworth AM1 (2010)—which was custom-built by motorbike maker Harley-Davidson—on a performance-art tour of Bavaria, accompanied by Alan Measles, his trusty teddy bear © Grayson Perry. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro; Photo: Angus Mill

Biography

Born: 1960 Chelmsford, Essex

Education: 1982 BA, Portsmouth College of Art and Design

Major shows: 2002 Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; 2006 Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; 2011 British Museum, London; 2015 Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; 2017 Serpentine Galleries, London; 2020 Holburne Museum, Bath; 2022 National Museum, Oslo

Represented by: Victoria Miro Gallery

• Grayson Perry: Smash Hits, National (Royal Scottish Academy), Edinburgh, 22 July-12 November