It may surprise some that it took over 40 years for Edward Hopper (1882-1967) to sell more than one painting. Throughout the early 1900s he experienced constant frustration and uncertainty, wandering between Europe, New York and New England in an attempt to cultivate a distinct voice. Driven by a staunch individualist ethos, Hopper refused affiliation with existing art movements and became somewhat of an outlier, languishing in obscurity and surviving on commercial illustration while his former art school colleagues achieved the sales and recognition that he longed for. Then, in the summer of 1923 he made for the coastal village of Gloucester, Massachusetts—a popular haven for artists—and everything changed.

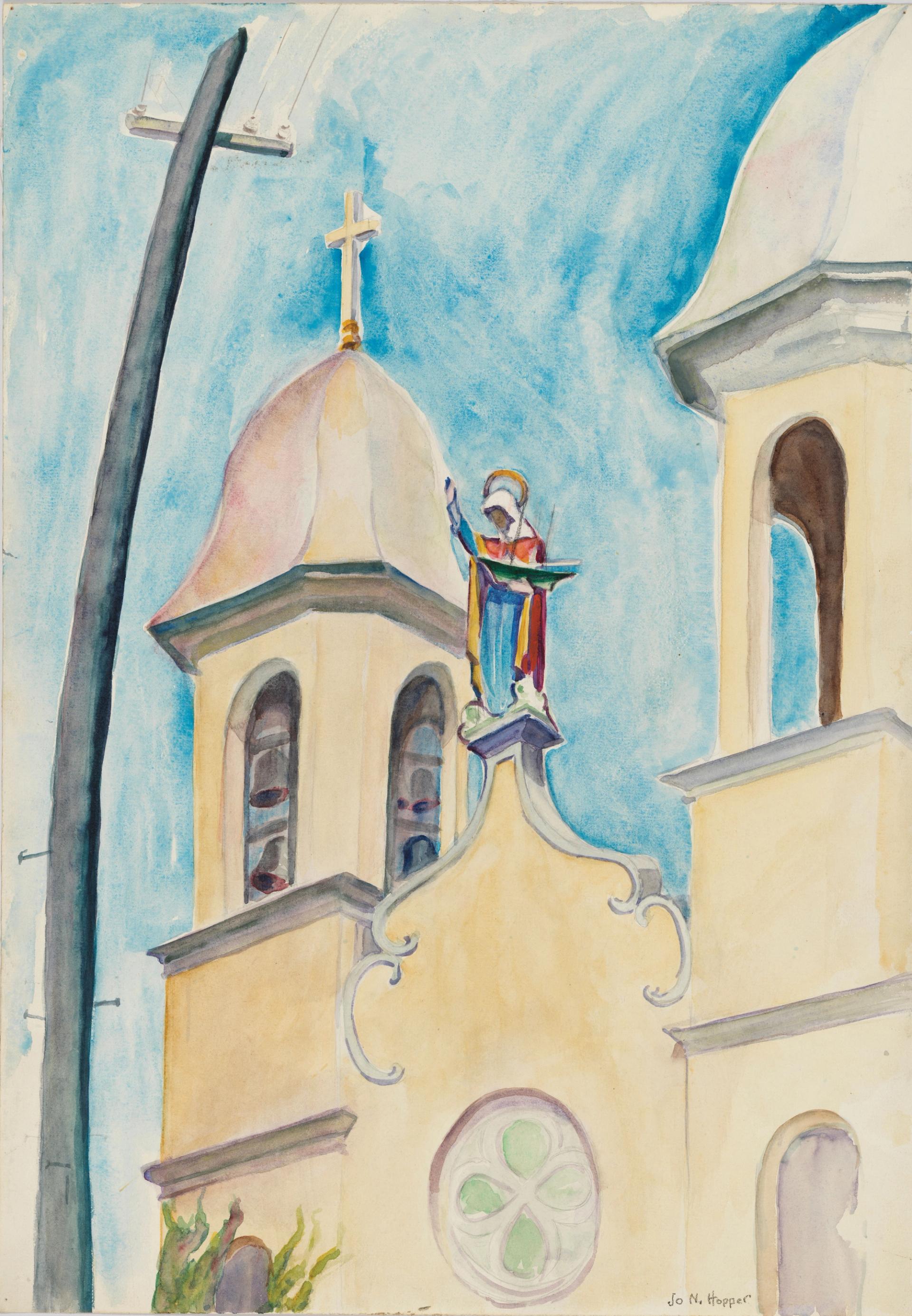

This turning point is the focus of a new exhibition, Edward Hopper and Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape. Curated by Elliot Bostwick Davis and presented in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art, it brings together more than 60 paintings, prints and drawings to examine how, across five summers, Cape Ann provided Hopper with the visual, cultural and personal means to upturn his artistic fortunes and define his mature style. Included are seven works by Hopper’s wife, Josephine (Jo) Nivison Hopper, who was an artist in her own right. Jo’s influence and contribution is a central focus of the exhibition, since it was in Gloucester during the summer of 1923 that Edward and Jo—who had met as students of Robert Henri at the New York School of Art—began the courtship that would lead to their marriage and lifelong creative partnership.

Church Towers, Gloucester (1923) by Josephine (Jo) Nivison Hopper © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by ARS, NY

Davis explains how the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue “represent the first extended focus on the artist’s five summers in Gloucester, combining visual evidence and reconsideration of published sources… to recast the role of fellow painter and future wife Josephine Verstille Nivison as Edward Hopper’s creative teacher, partner and producer.”

Through several pairings, the show explores Edward and Jo’s habit of painting side by side, as well as the potential impact that Jo’s painting might have had on Hopper’s own. Building on Hopper biographer Gail Levin’s foundational research on Jo Hopper, the exhibition foregrounds Jo’s decisive impact on Hopper’s trajectory, including his adoption of the watercolour medium at her suggestion and her lobbying for his inclusion in an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, where the sale of his 1923 watercolour The Mansard Roof served as the catalyst for his rise to fame.

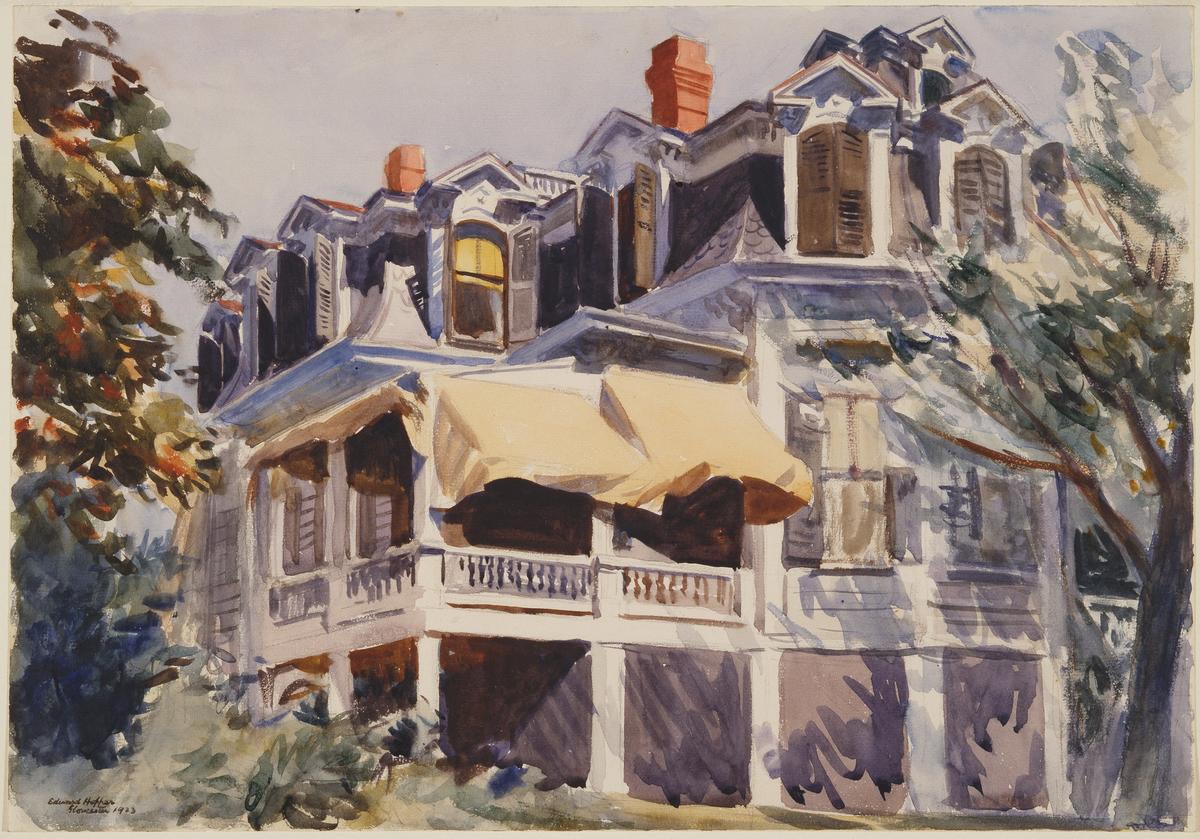

Hopper's Hodgkin’s House (1928) © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by ARS, NY

Throughout, Davis makes a case for Cape Ann as the essential formative environment of Hopper’s career, arguing that across the five trips Hopper made there between 1912 and 1928 he surmounted an awkwardness evident in his prior work, finding inspiration in Gloucester’s vernacular architecture and scenery to develop a distinct American iconography predicated on the poignant convergence of light and form.

• Edward Hopper and Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape, Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, 22 July-16 October