Tadao Ando burst onto the architectural scene at a moment when the decorative excesses of postmodernism and the engineering fetishes of high-tech were being diluted into corporate-commercial motifs. The Japanese architect’s austere concrete cubes, monastically minimal houses and theatrical, elemental chapels appeared as a kind of rebellion, an incorruptible return to the first principles of early Modernism yet infused with the contemplative aesthetic wisdom and material toughness of a martial arts monk.

He became the paragon of coffee-table minimalism. But only the most dedicated had seen his buildings in the concrete flesh. His work was mostly experienced through photographs.

But that was 40 years ago. Since those early days of impeccable concrete austerity, Ando has become a starchitect, one rewarded with major commissions dotted around the globe. Once the preserve of Japan specialists and minimalist obsessives, he is now revered by Asian corporations and the wealthy trustee boards of big cultural institutions. He has designed some of the most respected museums of recent decades, including the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St Louis, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and, most notably, a series of striking structures on the cult-art-pilgrimage island of Naoshima, Japan.

But the world of architecture moves on. Ando now belonged to an age of the lone male hero. The world’s gaze became directed towards social activism, minimising carbon (concrete finger wagging) and redressing the homogeneity of the profession. He had begun to look like a starchitect from another age.

Then, in 2021, the Bourse de Commerce in Paris opened (to perhaps less attention than it might have garnered had it not launched in the middle of a pandemic). Here was a fashionable reuse of a long-empty and historic structure, a heavily protected and listed gasometer of a space that appeared deeply unpromising as a home for art. Yet Ando turned it into something magical. Now a profoundly charismatic interior, it has demonstrated that this tough, wiry figure can still disarm with his architecture, can still surprise and delight.

“An architectural exhibition is, in a sense, a contradictory presence in which the true ‘work’ of the artist is not there, and only traces of the creative process are displayed”

Hiroki Nakadoi

© Tadao Ando Architect and Associates

A revered figure

I meet Ando in a side room of the LG Arts Centre in Seoul, a vast corporate concert venue for the Korean electrical giant. Surrounded by staff, with a crowd of photographers, journalists and PR people just out of frame, I had glimpsed Ando previously in another room signing books, each with an elaborate squiggle or sketch. He is clearly revered. What follows is a rather curious interview. I had flown halfway across the world for this rare opportunity because Ando has for a while now been living with cancer, and who knows whether there would be another chance to meet this architect whose works I had, as a student, pored over with such intensity and awe in obscure imported magazines.

Reported to now be missing a number of major organs, including his pancreas, gall bladder and duodenum, Ando has dark rings beneath his eyes and his skin is dulled by a faintly jaundiced pallor, but he appears otherwise surprisingly spritely. Dressed in a black turtleneck (de rigueur) and grey jacket, he boasts a thatch of suspiciously ungreyed hair.

The conditions for an intimate interview are notably absent, so I start big. What is architecture really about? “It is about hope,” he replies, speaking through a translator and perching on the edge of a large sofa.

“An architect’s duty is to convert feelings into physical form,” he says. “When I visited [Le Corbusier’s] church at Ronchamp I felt hope, the same when I visited the Pantheon in Rome. The light shining, the space … Architecture is not about physics and scale but about how big that hope can be.”

I mention to him how influential his drawings were during my student years, how we used to pore over those intensely shaded plans and meticulous sections. He is characteristically gracious. “If you say that my drawings had a positive influence on you when you were young, that is a great honour,” he says. Many of those drawings are now exhibited on the walls of Museum SAN, a building an hour from Seoul and designed by Ando. It is the final stop for a touring exhibition—Tadao Ando: Youth, until 30 July—that also took in the Pompidou in Paris, where it was credited with a bit of a revival in Ando’s reputation, a reminder of why he had been quite so influential for so long.

How was it to have an exhibition of his work in his own building? “An architectural exhibition is, in a sense, a contradictory presence in which the true ‘work’ of the artist is not there, and only traces of the creative process, such as drawings and models, are displayed. In that sense, the venue itself is the biggest exhibit, making this exhibition at Museum SAN extremely exciting for me.”

If architectural drawings are now exhibited on art gallery walls, and are increasingly collected by institutions, do they constitute a kind of art? “I feel that they are not,” he says. “Drawings are meant to be a means of conveying one’s architectural intentions to others.”

Ando was famously, and perhaps surprisingly, self-taught. There has been a large amount written about his short career as an amateur boxer (he gave up because he thought he wasn’t good enough), but I ask how he became interested in architecture. “In my mid-teens, the one-storey wooden tenement house where I lived was renovated into a two-storey building, and the young carpenter who took on the job was very enthusiastic about his work,” he says. “I thought to myself, ‘He’s really passionate. That’s impressive.’ If I had to pinpoint the moment when I became aware of ‘architecture’, that would be it.”

Why did he never study formally? “It was only due to my family’s financial situation and my own lack of academic ability that I couldn’t go to university, so it wasn’t that I chose self-study.”

The influence of Le Corbusier

I had read an enchanting story about the young Ando not having enough money to buy a book on his idol Le Corbusier, so he would visit the bookshop and surreptitiously trace the drawings. Was that really true? “That is not true,” he says, laughing. “I didn’t have enough money to buy it right away, so it took me almost a month to get it. Once I had it, I became obsessed with it and traced the drawings and perspectives every night after finishing my part-time job. I was determined to make it mine, no matter what.”

When I ask which building has had the most influence on him, it is hardly a surprise when he says Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel (1954), even though at the time of the opening of the Bourse de Commerce, I noticed he strategically switched to the Pantheon in Rome. The latter is, perhaps, a more interesting answer. In part at least because it is famously open to the elements, its oculus allowing sunlight and rain to enter the interior unmediated. The work that brought Ando wider global attention, the Church of the Light (1989) in Ibaraki, Japan, has a cross cut into the wall behind the altar. It has now been glazed but was originally open to the elements. In fact Ando initially considered a roofless space. Now entirely enclosed, it has lost a little of its elemental power and, looking around at the climate-controlled megastructure of the LG Arts Centre on the manufacturer’s huge Seoul campus, I can’t help but wonder if that initial connection with the elements represents something pivotal that has been lost? “This is a very significant discussion. Indeed, coexistence with nature is an eternal theme of my architecture,” he says. “That has not changed, but architecture has certain functions to fulfil. It’s not easy. I always struggle with where to draw the line between nature and artificiality as I proceed with design.”

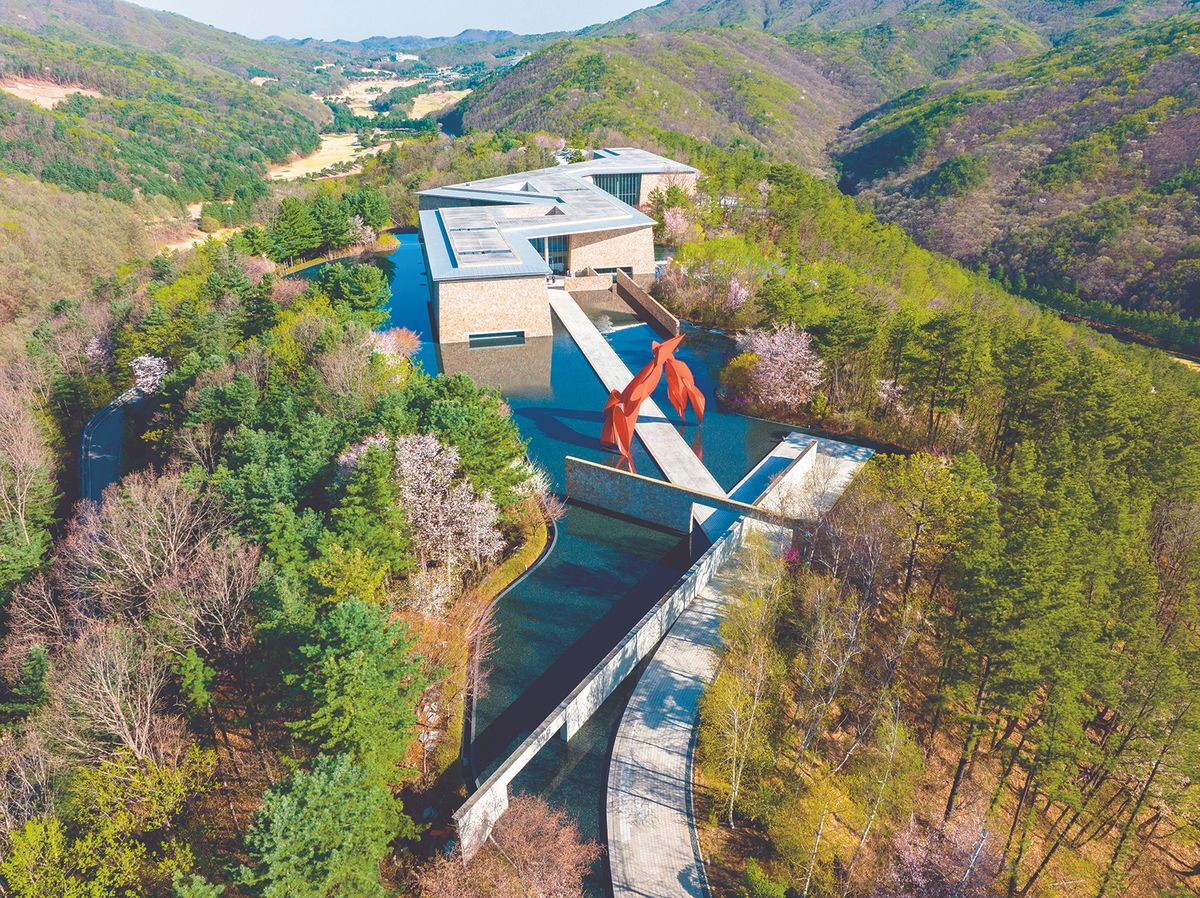

Museum SAN (the acronym stands for “Space Art Nature”)—a strikingly elegant building in a neatly maintained resort in the mountains of Wonju—exemplifies, in many ways, the crisis in contemporary architecture. Its version of nature is the golf resort, a certain kind of bourgeois luxury accessible only by car, yet also undeniably seductive as a manicured version of the natural world. Ando’s earlier austerity has faded into a more climate-controlled, global-museum-standard series of spaces. Ando was initially reluctant to accept the commission for the private museum (commissioned by the Hansol Group, a holding company mainly concerned with paper products), precisely because of the contingencies of its setting, its artifice. But it has become hugely successful with more than 250,000 people visiting the remote site each year. “Museum SAN was given a place with beautiful and rich nature,” Ando says, diplomatically. “The main theme was to maximise the potential of the land. As an answer to this, we designed an environmentally integrated art museum that unfolds while responding to the terrain, with indoor and outdoor spaces intertwined. We intended to create a building that feels like one big garden.”

In this, he is at least consistent—asked about his favourite art museum, he replies, without hesitation (as do so many other architects, notably Norman Foster): “The Louisiana Museum of Modern Art”—the exquisite 1958 masterpiece by Wilhelm Wohlert and Jørgen Bo. On the coast outside Copenhagen, the museum combines the contemplation of nature with the appreciation of art in an austere, Modernist design that appears very distant from the more overt architectural gestures of recent Ando (though his 1988 Church on the Water, a wedding chapel in Hokkaido, is a more obvious homage). So what does he believe a museum is for? “I believe that a museum is the light of hope,” he says. “A place where people can obtain the ‘nutrients for the soul’ necessary for living a rich and fulfilling life.”

Can a building overwhelm the art inside it? “I believe that the ideal relationship between architecture and art is one where they coexist, each as independent entities, stimulating each other.”

Creative building conversions

This takes us to the Bourse de Commerce. A project for Ando’s friend, the luxury goods magnate François Pinault (for whom he also designed the Punta della Dogana in Venice as well as some modest interventions at the Palazzo Grassi nearby), this reuse of the cylindrical former exchange building saw Ando erect a 30ft circular container at the centre of the rotunda. It also continues a later tendency of working with existing buildings—not something either Ando or his native Japan have ever been famous for. Yet adaptive reuse is increasingly looking like the future, perhaps even the only future in an age of climate crisis. “Reusing old buildings is not only important from the perspective of resource efficiency, but it is also an essential theme in considering the creative development of contemporary architecture,” Ando says. He talks of the concrete cylinder as “an architecture within an architecture” and of a “dialogue between the old and the new … [breathing] new life into the building”.

Finally I ask, a little hesitantly, about his health. Ando is an architect reputed to have been on the edge of death for a long while now. This brief trip has been billed as likely to be one of his last foreign excursions. Yet, frankly, he looks pretty well for a man of 81. “I have undergone two major surgeries and lost five organs in the past decade, but I have continued working as before,” he says. “I think this continuity is the best part of myself as a human being.” Then what, I ask—equally sheepishly—are the plans for succession in his office, a practice fiercely identified with Ando the individual? “I am currently thinking about various plans for the future of my studio,” he says. “This exhibition’s theme is ‘youth’, and I think that youth comes from a spirit of constant challenge, regardless of age.”

What, then, is the legacy? At this he pauses. “Architecture is about leaving something to the next generation,” he says. This is shaping up to be, perhaps, a less practised answer than some of his others: “Kenzo Tange’s Peace Centre in Hiroshima [1955] is a building which taught the value of life through architecture and building. This is the kind of building I’d like to leave behind. I’m not saying I have achieved it, but that is what I am trying.’

The entourage indicates that my time with Ando is over. I shake his hand (his grip is still healthy) and give him my business card. He looks at it, then draws a swirling, intense scribble to sign it.