Nine years after the launch of the second generation of blockchain, the technology has found a new life as a home for digital contracts. Artists and the art market have started to see delivery of the promise that blockchain—on which digital transactions are permanently recorded—can serve as a permanent record of a physical work’s authenticity, while also setting the terms for a secondary sale to benefit the work’s creator beyond the primary sale.

That promise derives from blockchain-powered ventures in other industries that are also trading high-value items, notably Everledger, founded in 2015, which secures records of authenticity and ethical sourcing for diamonds by tracking their provenance—including a “digital twin” of each gem—from mine to jeweller’s shop, through unalterable files held on a blockchain.

“Digital dossiers enable artists to add text, images and PDF files to create a rich provenance”

The art market, which enjoyed a rollercoaster first engagement with the blockchain as a home to non-fungible tokens (NFTs)—digital tokens that sold at eye-popping speculative levels in 2021—has been offered a new engagement with the technology in the past year, with the emergence of platforms devoted to using blockchain to host a digitised version of the established interaction between artists, dealers and collectors, in buying and selling new physical works of art.

Indelible record

The benefits on offer are a permanent record of authenticity and transparency of a transaction, to buyers and sellers alike, and allowing artists to set contractual terms, held on the blockchain, for the secondary sale of their work. (Makers of physical art will be looking to learn from the recent experience of those NFT artists who have sold their digital art on one blockchain but have then missed out on the terms of the resale royalties when the buyer has sold the piece on another blockchain.)

Two of the leading players in the field are Fairchain—a US-based start-up, founded by artists and Stanford University graduates, which since 2021 has offered blockchain-stored certificates of authenticity and royalties on resale—and Arcual. The latter, a blockchain-powered platform, backed by the LUMA Foundation, MCH Group (owners of Art Basel) and BCG X (the tech venture arm of Boston Consulting Group) bases its process on a double-signed agreement, the certificate of authenticity, between dealer and artist. These certificates “always include multiple signatures”, Arcual’s chief product officer, Rodrigo Esmela, and its chief technical officer, Michael Schuller, tell The Art Newspaper. This means, they say, “that parties cannot unilaterally define terms or conditions, allowing galleries and artists to define the accurate representation of the artwork on the blockchain and the terms and conditions of any sale or resale”.

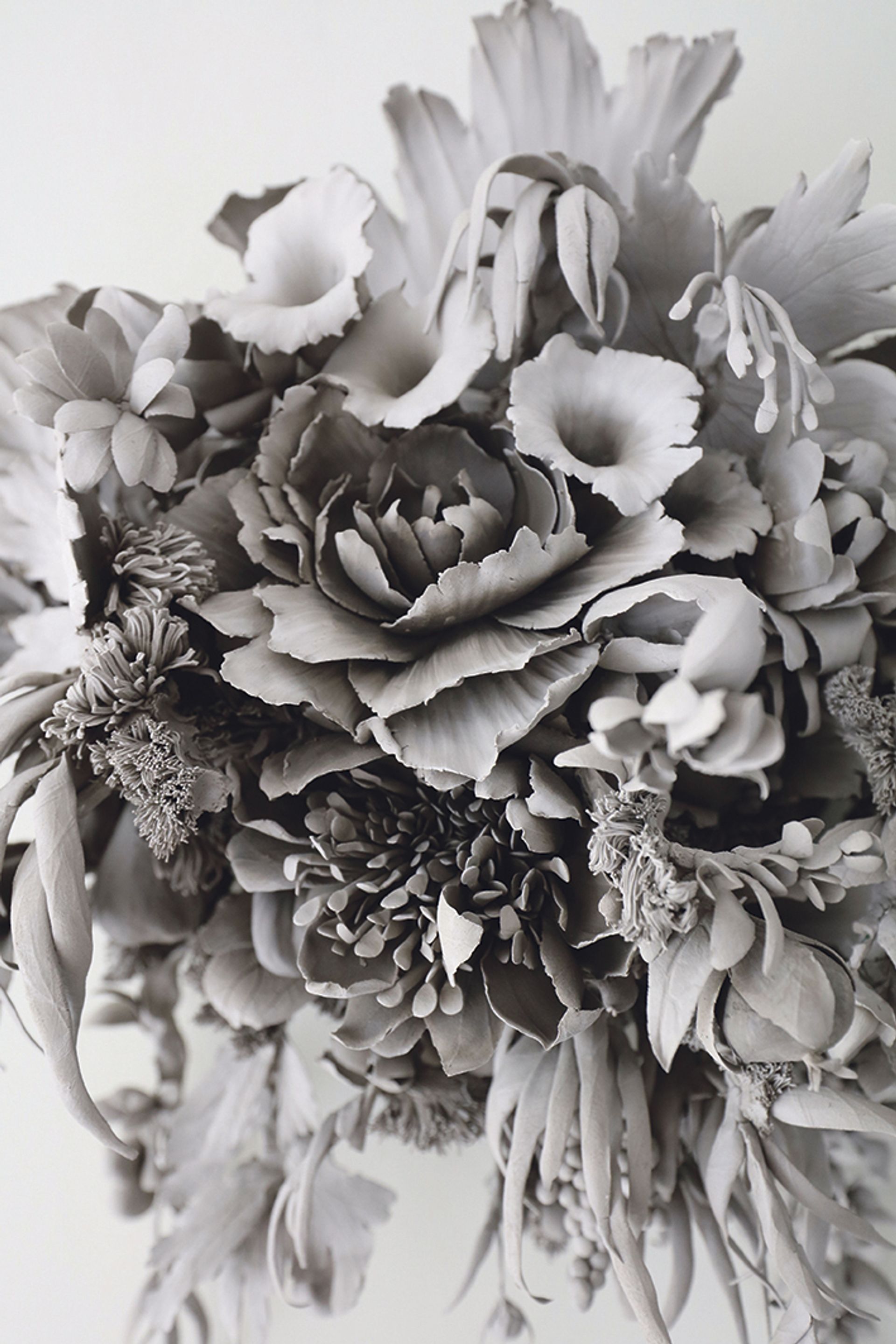

Works by Phoebe Cummings will be used by Arcual to demonstrate its digital dossiers at Art Basel

© Sylvain Deleu

Seven months after its launch, Arcual has introduced “digital dossiers”—which it will demonstrate at Art Basel with the work of the ceramic artist Phoebe Cummings—that enable artists to add text, images and PDF files to create a rich provenance, recording anything from the work’s creation to the artist’s intentions for its display. The information is as unalterable on the blockchain as its certificate of authenticity, and part of a smart contract between artists, dealers and collectors. (Arcual can handle transactions of up to $1m at a time and takes up to 1.5% in commission on each sale.)

Bernadine Bröcker-Wieder, Arcual’s chief executive, worked closely with Everledger in her previous role as founding chief executive of Vastari, the world’s largest private collection and temporary exhibition database, which took an investment in 2016 from Everledger. She says that, in conversations with artists, dealers and collectors, the word “blockchain” now hardly arises; the tech has almost become a given. And while blockchain-stored contracts designed for other industries—fashion, luxury, shipping containers—might depend on additional layers of tech to link contract and object, such as the creation of a digital twin or the adding of an NFT chip to high-value fashion items, in Arcual’s digital dossier an artist can record uniquely personal marks of authenticity. These might be a hard-to-detect symbol or a surface abrasion that forms part of a piece’s unique physical make-up, added by the artist for an extra level of authenticity. The Arcual dossier is like a “user’s manual of the work”, Bröcker-Wieder says.

Bernadine Bröcker-Wieder (above), chief executive of blockchain-powered platform Arcual

Photo by Jolly Thompson

Arcual’s digital dossiers are necessarily private to artist, dealer and collector, but the potential shape of such richly detailed provenances can be seen in platforms for other industries, including findmyinstrument.org, a website where the detailed history and physical characteristics of historic violins, violas and cellos, are published, using X-rays, infrared, endoscope imagery, photographs, video and written descriptions. Of course, storing large volumes of detailed information raises questions about data laws, especially in relation to the GDPR that prevails in Europe and the UK. Questioned about this by The Art Newspaper, Esmela and Schuller said that Arcual’s digital dossiers and other information held on the blockchain is compatible with GDPR. “We only store the minimum required information. No personal identifiable information (PII) about buyers is stored in the digital dossier, and only information relevant to the artwork is stored in the digital dossier.”

Artclear, another new blockchain platform for recording a permanent provenance for art, offers a technical model closer to the Everledger “digital twin” approach, by providing microscopic-level scanning of works using industry-standard tech under licence from the hardware giant Hewlett-Packard (HP). The scan, and a digital code derived from it, is saved on the blockchain as part of an Artclear Fingerprint.

Ceramic works by Athene Galiciadis were consigned by Arcual earlier this year

Courtesy of von Bartha Gallery Copenhagen

These new blockchain-based businesses have caught the attention of the market. At Art Basel in Hong Kong in March 2023, eight galleries consigned work through Arcual’s Salesroom platform, including Sabrina Amrani gallery with Carlos Aires and his sculpture Bon Appétit IV (2022), an assemblage of glassed porcelain plates, and Commonwealth and Council gallery with Kenneth Tam for his video Silent Spikes (2021). For Stefan von Bartha, the owner of Von Bartha gallery, which used Arcual to consign a Copenhagen exhibition of Athene Galiciadis’s painted clay vessels, Measuring the World, earlier this year, using the platform is part of striving “for a more transparent and fairer art world”.

As with all manner of new tech platforms over the past 15 years, whether in the art market, publishing, or gaming industries, potential customers of Fairchain, Arcual and other entrants to the field, are to different degrees enthused by the tech and wary of how it will reach critical mass. The London gallerist Oliver Miro, founder of Vortic, a VR and AR platform for the art world, recognises the potential of the technology but wonders whether this approach will work “unless the whole art world shifts to one model and one blockchain, and enforces it rigorously”.