Doris Salcedo’s Palimpsest (2013-17), now one of her most famous works, has been on show at the Beyeler Foundation since October last year. It is a huge floor-based installation in which names are written in sand on stone slabs. Periodically, other names, written in water, appear and overlap with them, before receding almost as quickly as they appeared. The names are those people who have lost their lives at sea: refugees, asylum seekers; the most vulnerable people in society, who sought safety.

In May, Palimpsest was joined by seven more installations of the Colombian artist’s work in a major survey, reflecting her consistent, unflinching focus on global humanitarian issues—political violence, human rights, the legacies of colonialism, the imbalances of the global north and the global south.

Though often alluding to the geopolitics and recent history of her native country, Salcedo’s work, she stresses, reflects the effects of an “interconnected” world. This aspect is emphasised in her most recent work, not in Basel, but in the recently closed Sharjah Biennial: Uprooted (2023), which uses dead trees to build an uncanny dwelling that alludes both to migration and the related climate emergency. “We are all in this together,” she tells The Art Newspaper. “It’s a fairly small planet. And everything that is happening in one place is connected to another place.”

The Art Newspaper: As you opened the Beyeler show, news emerged of asylum seekers in Greece being forced onto a boat and back to sea. Seeing Palimpsest installed across the world must be gratifying, but is there also pain in its eternal relevance?

Doris Salcedo: In a way I’m used to it. Maybe because I come from a country like Colombia, where we’re not used to seeing progress and development as such, but we are always immersed in this eternal crisis that entangles us every day. I’m used to the fact that what art does is mostly in vain, I would say. I don’t believe that we have the chance to save lives or to move consciousness massively. I just hope that maybe one individual might understand something and that understanding might be shared with somebody else. This is not an advertisement, we’re not the big press, we are unable to move awareness in that way. So it is extremely painful. But I know that is the nature of art. And it is exactly there where its poetic force resides. It’s not on the side of power, definitely. It’s a gentler, subtle, poetic task.

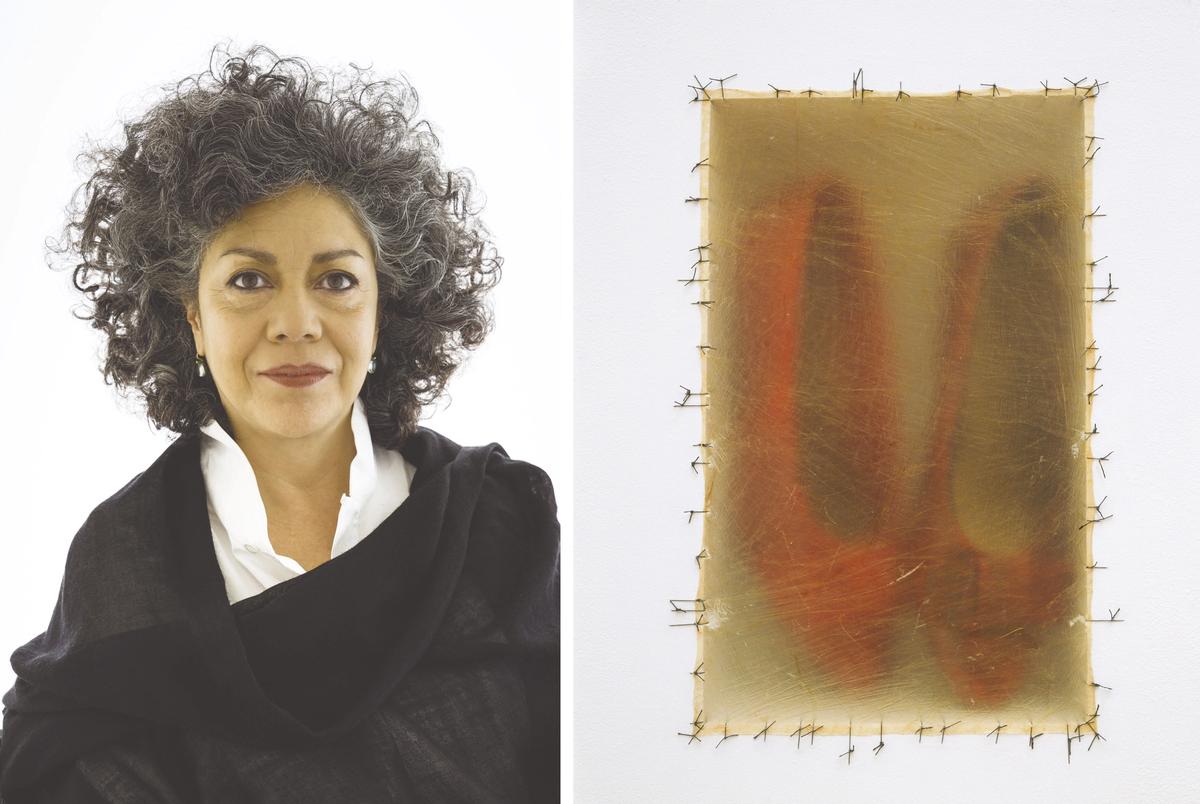

Salcedo’s Palimpsest, on show at the Beyeler Foundation, with its names of people lost at sea, is a haunting reminder of the global migration crisis

© The artist; photo by Mark Niedermann

The tension in Palimpsest lies in the contrast between that gentleness and the brutality of the subject matter.

It is like witnessing the disappearance of a life happening again and again in front of your eyes. So when the name that evidently signals a complete life is there, because of the water, it shines with clarity. And once the name starts disappearing, it’s like the drowning happens again. The mourning that the family lives is happening again and is being re-enacted continuously, as it is for the families that are maybe waiting, not even knowing what the fate of the person was, having that absence being the strongest presence in their daily lives.

Uprooted, in Sharjah, again relates to this subject of migration.

I began by thinking that I wanted to merge these two subjects that I believe are the most important subjects in our time: migration and, of course, the climate crisis. And I wanted to put those together, and the impossibility that a migrant has of ever owning a space on this earth. That’s why they are forced to die, either in the desert or in the sea. Because they are forced into those liminal spaces where it is impossible to live. The countries that are creating the largest number of migrants are also the countries that are most affected by the climate crisis, and are also the same countries that were brutalised by imperialism and colonialism.

On top of that, they are the countries now receiving all the toxic waste that the global north is exporting. It’s just unbearable, the condition that we are forced into. So I wanted to address all these issues in this work. But once the piece was finished, I realised I was not only addressing the condition of the migrant, or of the global south, but I was addressing the condition of all of us. We are all losing our common home. So the meaning of the work expanded for me.

Does there need to be a correlation between the difficulty of making the work and the difficulty of tackling the subject?

I always talk about the works that I make being almost impossible to make. I push myself to the limit. And when you see it finished, you don’t really understand how that could be done. That impossibility goes together with the impossibility of the conditions, the extreme difficulties that victims, refugees, and now all of us are facing. So it is intimately related.

I think, sometimes, of absurd gestures. If there is a huge waste of life, in political violence, I need to achieve a gesture that is absolutely absurd, that shows that waste of energy, that waste of life. So I do things that go against the logic of the means of production of our society: I embroider in wood, which is absurd [in the series Unland (1995-98)]; or I make a huge shroud of rose petals, which is completely absurd [in A Flor de Piel (2012)]. So this absurdity shows the extreme difficulty and extreme experiences that I research carefully and try to address.

Salcedo’s assemblage of an armoire, concrete and clothing, Untitled (1998), is a response to loss and trauma

© Doris Salcedo; photo by David Heald

You’ve spoken about how emotion is alien to much Western contemporary art. And yet you use some of those languages—Minimalism, the found object and so on—to communicate maximum emotion.

Yes, it’s like, feelings and emotions are dirty words in art. Everything is supposed to be neutral and dry. I think it is the fact that I come from the global south. And now I’m telling stories full of emotion, stories that are based on real events, stories that have not been told and there is a huge need to tell them.

When I was young, I grew up being told that I belonged to an underdeveloped society; my mind was underdeveloped, our art was underdeveloped, our economy, our industry. Can you imagine how brutal it is for a person to grow up knowing full well that you are underdeveloped? Little by little, I started thinking that is not the case. We all have the same abilities and the same capabilities.

We just have to tell the story backwards. So we certainly are inserted within the canon of Western art, because any other art was entirely destroyed by European imperialism. But we have to turn that canon upside down to tell our stories. And in that turning-upside-down, emotion has to come through because the amount of pain that the society has had to withstand is enormous. So it has to be presented, it has to be shown. And there’s no other way but with feelings.

One of the ways you do that, of course, is through metaphor. And there is a direct correlation again, between material and metaphor. Do those metaphors arise as an epiphany or through hard-won work with materials in the studio?

It is both. Because I do work very intensely researching, interviewing, and drawing and sketching, literally for years. And then all of a sudden there is epiphany. And then the work is complete. In most cases, the work is complete at once. When it shows up in a drawing, the materiality is there… I don’t dare say that I think of it—it just shows up, like it’s been told to me. And then it appears. Of course, I have to do material testing. But it’s clear there is going to be tears or water, or it’s clear that it has to be concrete, or dead trees. It shows up like that in a sketch, complete as an almost finished piece. And then, of course, the struggle of refining the materiality. But it is both.

• Doris Salcedo, Beyeler Foundation, Basel, until 17 September; Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present, closed 11 June

• Listen to our interview with Doris Salcedo on the A brush with... podcast