One of Andy Warhol’s closest friends, the writer and photographer Bob Colacello, is showing a series of photographs from the 1970s and 1980s capturing the people and parties of the time. It Just Happened 1976-82, a new exhibition in London at Ropac Gallery (until 29 July), includes images of Warhol with his artist peers, pictures of parties at The Factory and Studio 54 and intimate snaps of The Pope of Pop.

Colacello was the editor of Interview magazine, Warhol’s famed celebrity chronicle, between 1971 and 1983. On one of his many trips abroad with Warhol, the young Zurich art dealer Thomas Ammann showed up at Andy's hotel suite with the brand-new Minox, the first miniature camera to take full-frame photos, Colacello explains.

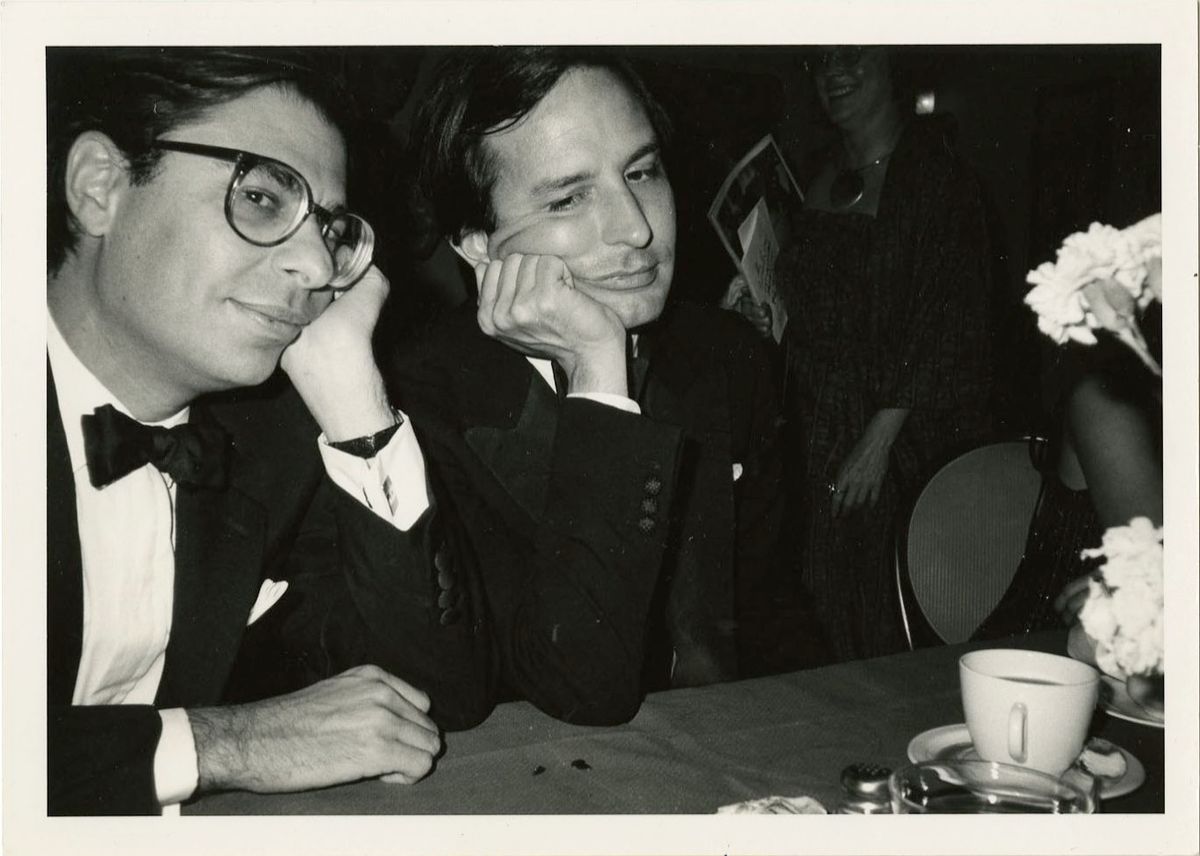

Colacello whipped out the Minox to capture politicians, artists and confidantes. “There is a rarity factor to all these photos,” Colacello says. “Andy did not bring a professional photographer along [on his trips]—they were taken in places where there were no photographers. I was part of the Warhol family, nobody cared if I took their picture.”

This form of surreptitious photography is a kind of "amateur photojournalism," Colacello says. Though "over time, I started to realise that I did know what I was doing. I liked that somebody unknown was blocking somebody very well known,” he says.

Photography was not considered fine art in the 1970s, stresses Colacello. “We did a piece in Interview in 1975, asking is photography art? Photography was called an applied art, like fashion, it was not a fine art, like painting, sculpture, and printmaking or drawing. The big breakthrough was when Richard Avedon had his exhibition in Marlborough Gallery [late 1975]; that’s when we decided to do an art and photography issue.”

In the London show, a wall of images show a range of major 20th-century artists including Robert Mapplethorpe, Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg. “The truth of the matter is that Andy was not really so admired by the New York art world in the 1970s… Jasper Johns looked down on him, Rauschenberg was a little nicer. Roy was a friend. Mapplethorpe and I were friends but he didn’t want to hang around Andy because he said he’d steal his ideas. And Andy hated him for saying that.”

Another image, Andy's Room Service Breakfast, Naples (1976), shows Warhol having breakfast in his Brooks Brothers shirt, Jockey shorts and Supp-hose socks at a hotel in Naples. The pop artist’s vulnerability is striking. “Andy didn’t really like to be touched,” says Colacello who recalls a tense exchange at a hotel in Paris. “He was asleep on his bed, so I slowly took his boots off. He shouted, what are you doing? He protected himself by having a tape recorder in one hand and Interview in the other.”

Colacello also describes how the Ladies and Gentlemen paintings—Black American and Latinx transgender women and drag queens painted by Andy Warhol in 1975—came about. The works, shown at Tate Modern in 2020, were commissioned by Warhol’s Italian dealer Luciano Anselmo in 1974, who asked the artist to depict “funny looking” drag queens.

Warhol subsequently asked Colacello to find sitters, offering a $50 fee to each model. Colacello discovered prospective candidates in New York’s Gilded Grape club off Times Square, a magnet for members of the trans community. Warhol took Polaroids of the models, then transferred the images onto silkscreen, completing the canvases by covering them with synthetic paints.

Anselmo said “I want you to do a series of drag queens but unsuccessful drag queens.”

Warhol said: “Bob has a heavy beard, he could be the model.” So Colacello stepped in, dressing up in drag in exchange for a work by Warhol. But the experiment was unsuccessful as Colacello didn’t “hold his hand like a drag queen”, according to Warhol. “As paintings, they’re among Andy’s most beautiful. They’re very heavy; the colour combinations are amongst the most daring. I love those paintings,” Colacello says.

Colacello studied international affairs at Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in 1969, then went on to study film at Columbia University, New York. He began writing film reviews for Village Voice around the same time, which caught Warhol’s eye.“One night about 7.30, I was having dinner [at my parents’ home in Long Island], the phone rings and this guy, Soren Agenoux, told me he was working with Warhol and was editor of the new mag Interview. Andy wanted to meet me, he’d been reading my reviews.

“I was beside myself—oh my god Warhol wants to meet me. But my father said: ‘I forbid you to meet that creep who makes movies about boys who want to be girls. I will break your legs, I will break your movie camera.’ But of course I couldn’t wait to run down to Union Square to meet Warhol the next day.”

But did his father soften? “Yes, when I was able to tell him that [former US vice president] Nelson Rockefeller came down to The Factory to buy some paintings. Within a year, my parents were having Andy and his boyfriend Jed Johnson come out for spaghetti and meatballs for Sunday lunch.”

Colacello says that he is “a diehard Republican. But I’m not a Trump Republican. I think American politics is in a very scary and depressing place; there are a lot of clowns and no leaders. Ronald Reagan-style conservatism is about individual freedom.” But how does he square his political views in the seemingly progressive art world? “I’m an iconoclast; in the art world, everyone is Democrat so I’m going to be Republican.” In 2004, he published Ronnie & Nancy; Their Path to the White House 1911 to 1980.