Art may be one tool to help bridge ideological splits over climate change in the United States, a new study in the 31 May issue of the journal Nature finds. Its five authors say that art offers an accessible way to engage with and understand climate change, and that artistic visualisations of data appeal to viewers’ emotions more than standard data graphs. This engagement has the potential to reduce the polarising effects of graphs, which may heighten scepticism and actually exacerbate political division on climate change.

The peer-reviewed study offers what its authors describe as “pioneering evidence” of this impact. “Such emotional experiences may motivate spectators to reassess the visualised data that contradicts their beliefs and reduce the perceived distance to climate change,” they write. “Our findings not only inform ongoing conversations about how science and art can work together to reckon with the impending environmental crisis, but they also suggest new opportunities for practitioners and researchers in climate science, communication, environmental humanities, psychology and sociology to continue collaborative, interdisciplinary work in this area.”

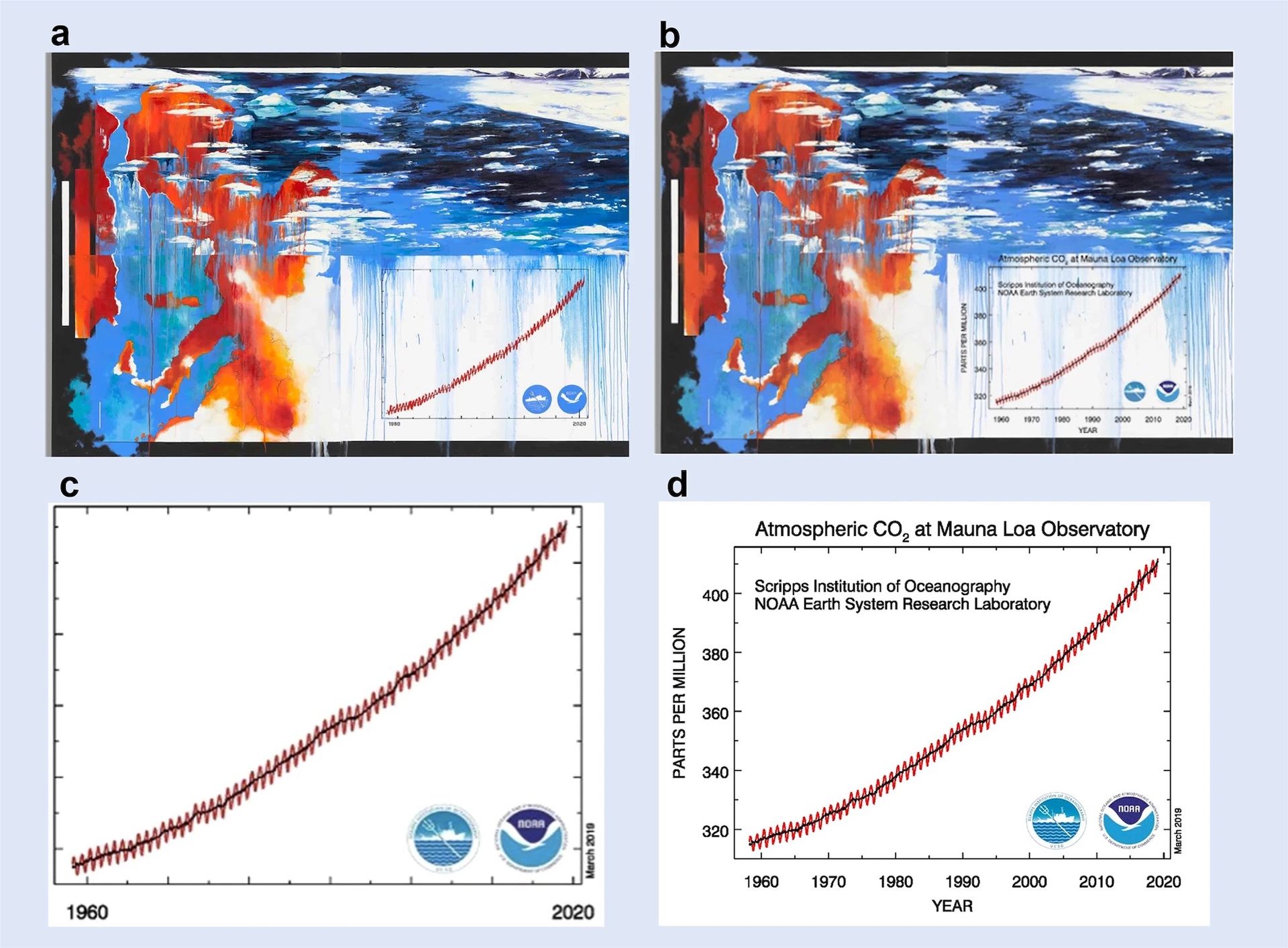

To test the efficacy of artistic representations of data, the researchers conducted two experiments in which they showed participants in the US artistic and scientific visuals of the Keeling curve, which records the accumulation of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere. The 671 total adults were asked to report their political ideologies, pre-existing concern with climate change and levels of interest in art. The artwork chosen, titled Summer Heat (2020), by the painter and photographer Diane Burko, depicts an abstracted map of Europe against a backdrop of melting glaciers, accompanied by a simplified version of the Keeling curve.

a: The original artwork Summer Heat, 2020, by Diane Burko. b: The edited art piece with the detailed Keeling curve graph. c: The edited, simplified Keeling graph. d The detailed Keeling curve graph. Artwork image courtesy Diane Burko. Graphics courtesy Nan Li, Isabel I. Villanueva, Thomas Jilk, Brianna Rae Van Matre and Dominique Brossard

In the first experiment, 319 participants examined Burko’s original work as well as an edited version of her work with the detailed Keeling graph in place of the simplified one. They were also given two images of the graph alone—one simplified and one detailed. Researchers then asked them to reflect on the works, asking whether they felt emotions such as hope, inspiration, guilt, anxiety, fear or a sense of awe. Participants were then given the four images as mockups of Instagram posts, complete with informative captions, and asked multiple-choice questions to test their recall. Instagram was chosen due to its outsize role in circulating infographics, allowing “scientist-artists to reach out to audiences that are less frequent visitors of science museums and art galleries”, the study’s authors write.

Overall, participants had stronger positive emotions in response to the artistic visualisations than the data graphs, the researchers found. They also perceived the Instagram posts with the creative imagery to be as memorable and as credible as those of the straightforward data. Additionally, when prompted to reflect on the artistic visualisations, participants were “less politically polarised in their perceived relevance of climate change” than when viewing the graphs. A follow-up study, in which 352 adults were shown only the Instagram posts, and not asked to reflect on these viewings, revealed a similar relationship between political leaning and understanding of climate change.

The ability of engaging visuals to tap into emotions and ease education on hot-button topics may not be surprising to those who work in the arts. But having this empirical evidence is important for both artists and institutions, especially because creative engagement around the climate crisis is increasing, says Miranda Massie, founder and director of the Climate Museum, the first museum of its kind in the US.

“It’s going to be hugely inspiring for artists to have this social-science confirmation of something that they already intuitively feel and have seen in operation,” she says. “At the Climate Museum, we’ve seen this in reality in the way our visitors quite uniformly respond to our work about climate. The social science is still very helpful and confirming.”

The Climate Museum, which opened in 2018, operates through pop-up exhibitions and events. It has worked with artists including Sara Cameron Sunde, Gabriela Salazar and Justin Brice Guariglia to engage with issues of rising sea levels, climate inequality and the fossil-fuel industry, among others. The exhibitions, Massie says, intend to motivate people who are concerned about climate change but feel uncertain about what to do. “We’ve always seen a side benefit of bridging ideological divides,” she adds. “Art opens up both our hearts and our minds…in opening people up and causing us to see our connections to other people, inevitably, you’re also going to break down some of those preposterous divides that have been fostered in the climate-change debate.”

The authors of the Nature study acknowledge that findings obtained from a singular work of climate change–inspired art by an American artist may not apply to all such works. Additional research, they say, needs to be done to explore various types of science-based art and their effects on people living outside the US, particularly in communities who are disproportionately affected by climate change.

“It’ll be great to see other people build on this research, extend it into other venues and explore other questions about community engagement,” Massie says. “There’s a remarkable power that the arts have to open people up to scientific information, to social information and to their sense of belonging and ability to make change. That superpower of the arts is not something that humanity can afford to leave on the ground at this point in climate change.”