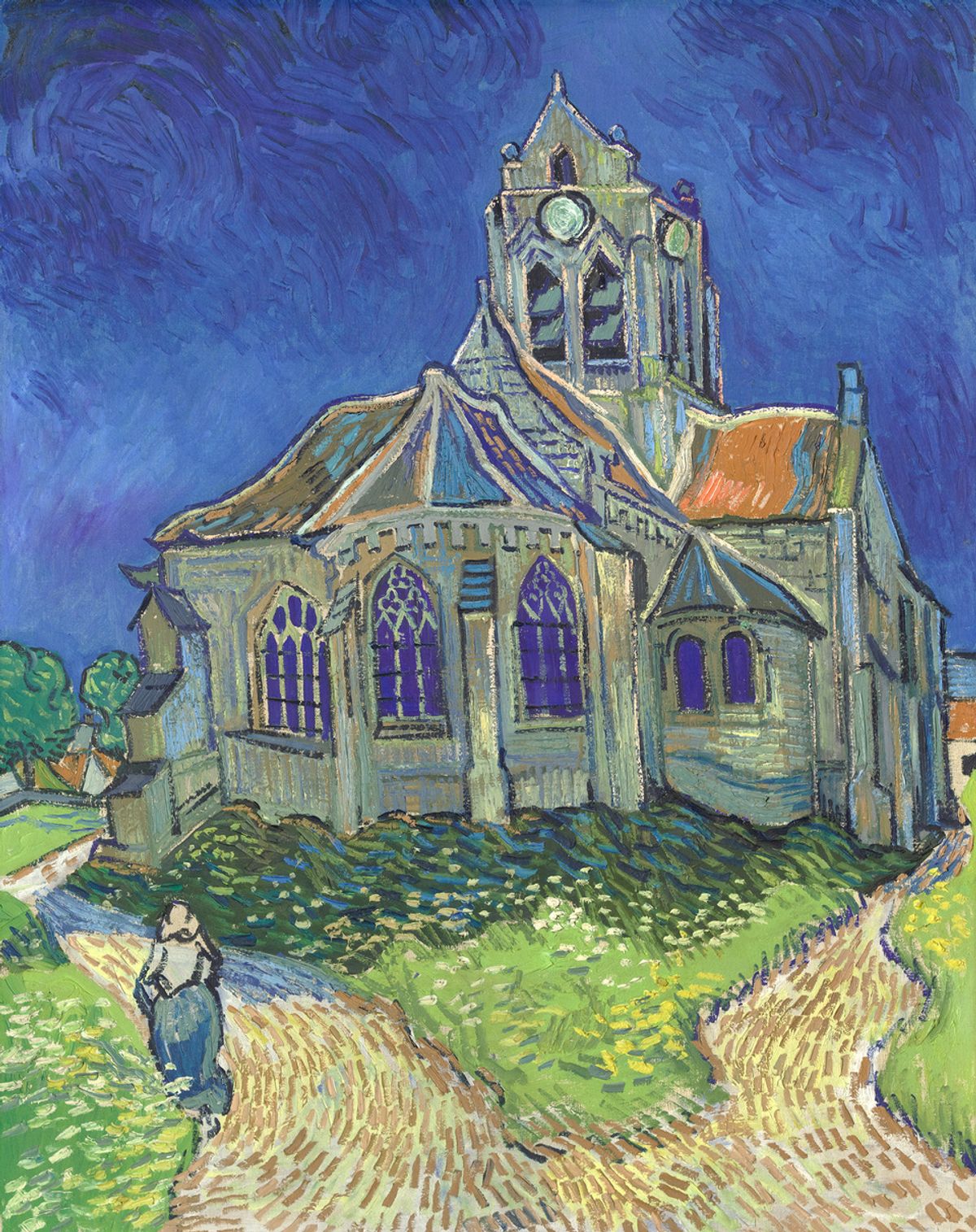

Van Gogh painted his memorable Church at Auvers (June 1890) in the village where he lived at the end of his life. The picture is among the stars in the Van Gogh Museum’s newly opened exhibition Van Gogh in Auvers: His Final Months (until 3 September), on loan from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris where the show will be presented in the autumn. It is the cover image for the Amsterdam catalogue.

Cover of the catalogue for Van Gogh in Auvers: His Final Months (detail) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

The Catholic church of Notre-Dame stands only five minutes’ walk from the inn in Auvers-sur-Oise, just north of Paris, where Van Gogh was staying in the early summer of 1890. The church’s hillside location means that the tower would have been visible from many of the places where he painted, so he knew it well. Nevertheless, it seems a surprising choice of subject for him.

Van Gogh came from a Protestant family and had long ago abandoned organised Christianity, so the religious significance of the Catholic church meant little to him. Although it is an important Romanesque monument, dating back to the 12th century, he was uninterested in imposing architecture. Van Gogh may well have entered the church out of curiosity, but its stone interior is unadorned and the few religious paintings would hardly have caught his eye.

On 4 June 1890 Van Gogh set up his easel in the churchyard, facing the apse, which thrusts forward beneath the bell tower. A comparison with early photographs shows that he depicted the scene reasonably accurately, although he used sinuous lines, bringing the structure to life rather than conveying it as static architecture. The result is a powerful work: whether or not intended, the radiant church seems to exude spirituality, soaring heavenward.

Church of Notre-Dame, Auvers-sur-Oise (around 1900)

Credit: Archives départementales du Val-d’Oise, Pontoise (inventory 2 F 293)

The diverging paths running along the sides are painted with powerful, agitated brushwork in what were originally pinkish tones. Today, after the artist's red pigment has faded, they have become a less dramatic beige. Spring flowers grow on the lush, fresh grass. A woman scurries past, adding movement to a timeless scene.

The picture derives its greatest impact from the sky, a blend of shades of blue that grow deeper towards the top. It might even appear to be stormy weather, but the shadow cast by the apse confirms that it is a bright, sunny afternoon. The windows, in a deep blue, almost suggest that one can look through the church towards the sky.

Vincent described the picture to his sister Wil: “I have a larger painting of the village church – an effect in which the building appears purplish against a sky of a deep and simple blue of pure cobalt, the stained-glass windows look like ultramarine blue patches, the roof is violet and in part orange.”

Van Gogh’s The Old Tower (May 1884) Credit: Emil Bührle Collection, Zurich (displayed at the Kunsthaus)

There are striking parallels between this Auvers painting and Vincent’s depictions six years earlier of the church tower in the Brabant village of Nuenen, where his father served as the parson. Conscious of the link, Vincent told Wil that his latest picture was “almost the same thing as the studies I did in Nuenen of the old tower and the cemetery.”

Although similar in approach, the huge differences between the Nuenen and Auvers paintings emphasise the dramatic development of Van Gogh’s style – moving from the sombre tones of his Dutch period to the bright palette and strong brushwork of his later French years. As Vincent put it to Wil, his colouring had become “more expressive, more sumptuous”.

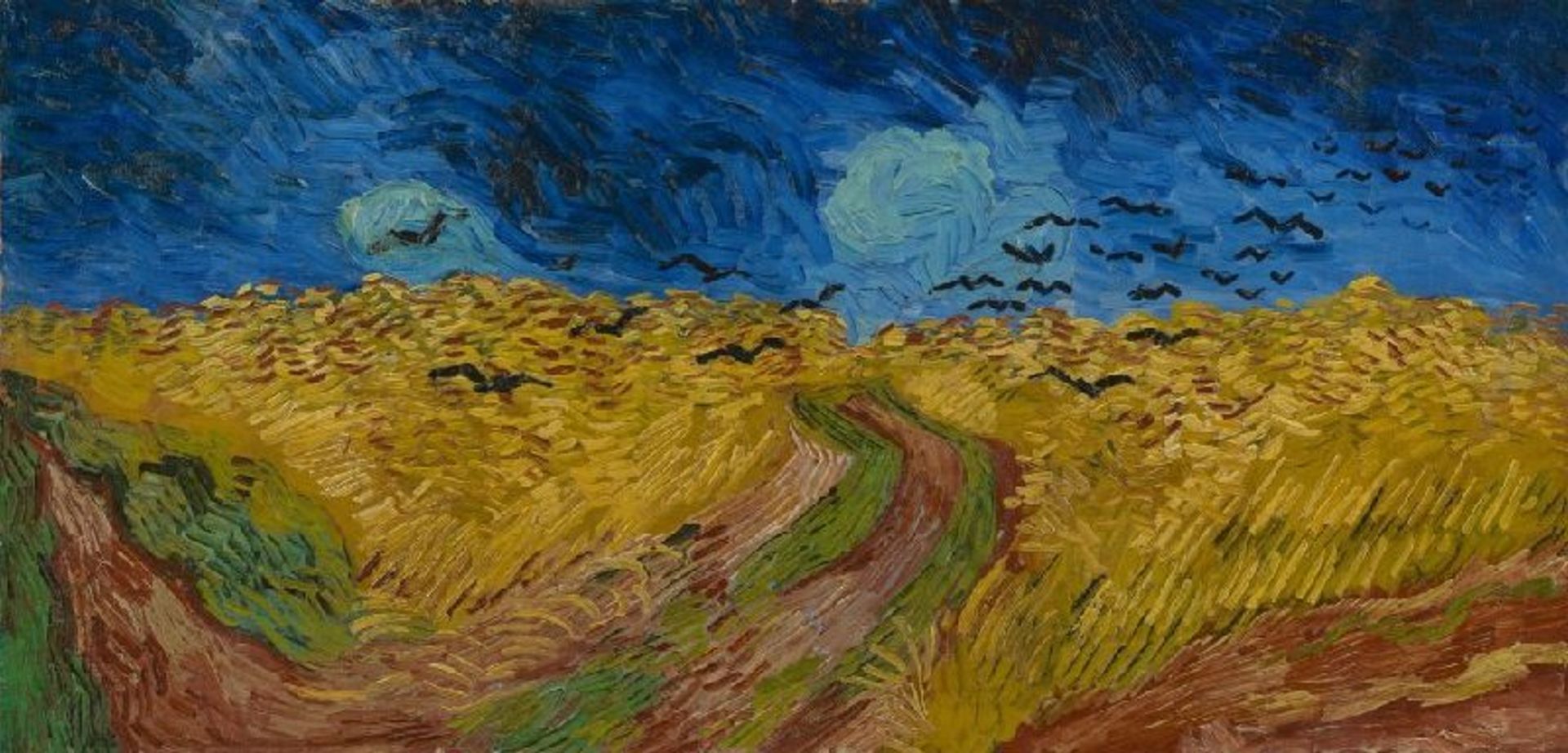

Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows (July 1890)

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

What has gone largely unnoticed is the similarity of the paths in Church at Auvers with those in Wheatfield with Crows (July 1890), painted three weeks before Van Gogh shot himself. The panoramic wheatfield picture is usually regarded as revealing something of his tortured mental state, prior to his suicide. Although the configuration of the diverging tracks is similar, the sunshine and human presence imparts a very different mood in Church at Auvers.

After Van Gogh’s suicide his coffin was held for a few hours in the inn, with friends and neighbours arriving pay their last respects. The coffin was then surrounded by his latest paintings, including Church at Auvers.

The village church was asked to lend their hearse, to enable Van Gogh’s body to be taken up the hill to the cemetery. But the priest, Henri Tessier, refused, because Van Gogh had committed suicide. Although no longer a criminal offence in France, it was still regarded as sinful by the Catholic Church.

As for the painting, it was given to a local resident, Dr Paul Gachet, who had cared for Van Gogh at the end of his life. He hung Church at Auvers above his fireplace, in a plain white frame, a simple style which Van Gogh would have appreciated. After Dr Gachet’s death his son allowed very few specialists to view the picture and forbade it to be photographed. The painting therefore remained largely a secret, even after the artist had become famous.

Gachet Jr transferred Church at Auvers to the Louvre in 1952 (and it later passed to the Musée d’Orsay). On acquisition, it was valued at 15m (old) francs, but Gachet Jr generously accepted 8m. Although the Musée d’Orsay’s website records that this was paid by “an anonymous Canadian donation”, we can report that it came from New York-born Princess Winnaretta Singer-Polignac, who lived in England, but whose estate had passed to a Canadian entity after her death in 1943.

Church of Notre-Dame, Auvers-sur-Oise Credit: The Art Newspaper

The church building is now visited by thousands of visitors every week, who come to see the spot where Van Gogh painted Church at Auvers. They then end their pilgrimage by walking a little further up the hill, to pay homage at the simple gravestones erected for Vincent and his brother Theo.

Graves of Vincent and Theo, Auvers-sur-Oise Credit: The Art Newspaper

Other Van Gogh news:

Van Gogh’s Poppies and Daisies (June 1890), which sold for $62m at Sotheby’s, New York, 4 November 2014

The New York Times has investigated the fate of Poppies and Daisies (June 1890), which was sold at Sotheby’s in 2014 for $62m. Painted in Auvers, it was originally owned by Dr Gachet.

The article reveals that although Chinese entertainment businessman Wang Zhongjun was named as the buyer, the ownership is apparently much more complicated. There was an obscure middleman in Shanghai, Liu Hailong, who paid the Sotheby’s bill through a Caribbean shell company. The person he answered to was a Hong Kong billionaire, Xiao Jianhua, who is now in prison in mainland China. apparently for bribery of officials and manipulating financial markets. The New York Times reports that the Van Gogh is once again up for a privately arranged sale.

Although Poppies and Daisies was promised for Van Gogh in Auvers: His Final Months and is in the catalogue, it failed to turn up for the exhibition.