As a culture war around issues of trans and gender-non conforming identities rages on, an archival exhibition in Bethnal Green, east London, emphasises how queer communities the world over have been placed at the forefront of politics for decades, and played central roles in resistance movements.

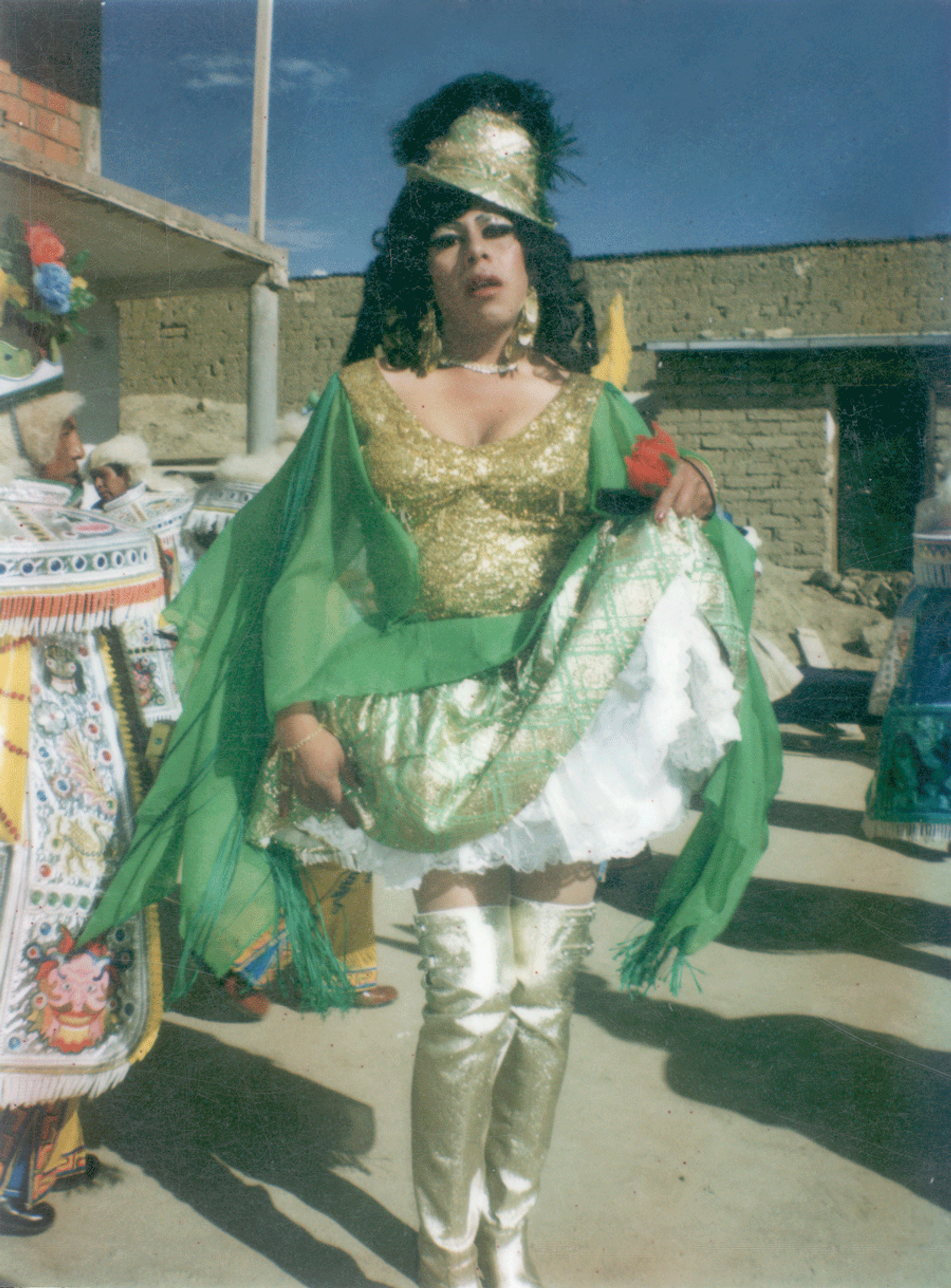

Barbarella’s Kiss (until 11 June), at the curator-favourite non-profit space Auto Italia, surveys the work of the Bolivian artist and queer activist David Aruquipa Pérez, who has amassed a collection of photographs of his travesti friends (a Latin American-specific term for gender non-conforming people assigned male at birth) performing at carnivals from the 1960s to the 1980s. Many of them embody the character of the China Morena, a flamboyantly dressed feminine figure popular at Bolivian carnivals, and which Pérez asserts originated with trans communities.

“The parades are catwalks—the fashions dictate those in normal society and the China Morena are hugely influential,” Pérez said shortly before the show’s opening, for which he transformed into a China Morena, wearing a bright red dress, and performed a dance accompanied by a soundtrack of recordings from historic carnivals to “invoke his sisters both dead and alive”.

David Aruquipa Pérez's Lucha (Luis Vela) at a rural festival, La Paz, Bolivia, c. (1973) colour photograph

Courtesy of the artist and Diversidad – Comunidad de Investigación Acción en Derechos y Ciudadanía

The exhibition takes its title from an incident—of which no photographic evidence exists—in which the travesti Barbarella kissed the Bolivian dictator Hugo Banzer Suárez at a carnival in 1974. Humiliated and enraged, Banzer banned the travesti from performing and drove them underground. But in doing so, he also served to emphasise their subversive role in the wider resistance movement that would topple his military rule in 1978.

"Barbarella's Kiss is a document of sexual and gender diverse people's fight for fair and equitable inclusion with culture and society," says Auto Italia's director Edward Gillman. He relates the show's themes to the ongoing fight for liberation among trans and gender-nonconforming people in the UK. "The exhibition evidences that gender diversity is rich and kaleidoscopic, and that the human experience encompasses a complex range of live gender experiences—more than the mainstream political-religious right in the UK would like us all to believe."

Pérez, who worked with the curators Milda Batakyte and Aitor González to organise the show, emphasises how central carnivals are to Bolivian society. "To be visible in the carnival is participate in society—everyone is watching you. And when your presence is banned, the mere act of gathering becomes one of resistance."

The simultaneous repression and hyper-visibility so often faced by trans and queer people was addressed in a talk at the exhibition, for the launch event of Viscose—a fashion theory magazine that has dedicated its fourth issue to issues of transness in fashion. “Dressing is a public act,” says Viscose’s founder Jeppe Ugelvig, “and the images of the Chinas Morenas, as well as this current issue of the magazine, both underline how gender nonconforming people have long been at the forefront of politics,” he says, adding that one must always look to the fringes and undersides of society to properly observe how fashion and power interact.

Viscose's Trans issue contains a number of historic, archive articles that show, among other things, how attitudes towards gender identity have in some ways become more, not less, reactionary over time. It reminds us that the roads to freedom, both social and legal, are not always linear, nor are they geographically siloed. But while it is a troubling fact that something so innocuous as a garment can still cleave a nation’s politics, there is power too in remembering that the act of wearing a dress can help bring down a dictatorship.