In the early 1890s, Munich could lay claim to being the artistic capital of central Europe. Home to a cluster of so-called “painter princes”, known for their grand history scenes and society portraits, the city seemed to be a bulwark of academic standards against trends, some decades old, brewing over in France.

By 1892, Munich’s younger, progressive-minded artists had had enough, and they broke away to start their own organisation and mount their own exhibitions. In 1897, Vienna artists followed suit, and in 1899, when it was Berlin’s turn, the phenomenon adopted a Latinate byword—“secession”— in its name and began to lay the groundwork for the rise of Modernism throughout German-speaking Europe.

The engine of all the secessions was that art should be newRalph Gleis, director, Alte Nationalgalerie

Covering the period from roughly 1890 to the brink of the First World War, a new show, opening this month at Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie, considers the origins and manifestations of these developments by presenting some 220 works in a wide range of media by 80 artists associated with one or more of the three secession groups.

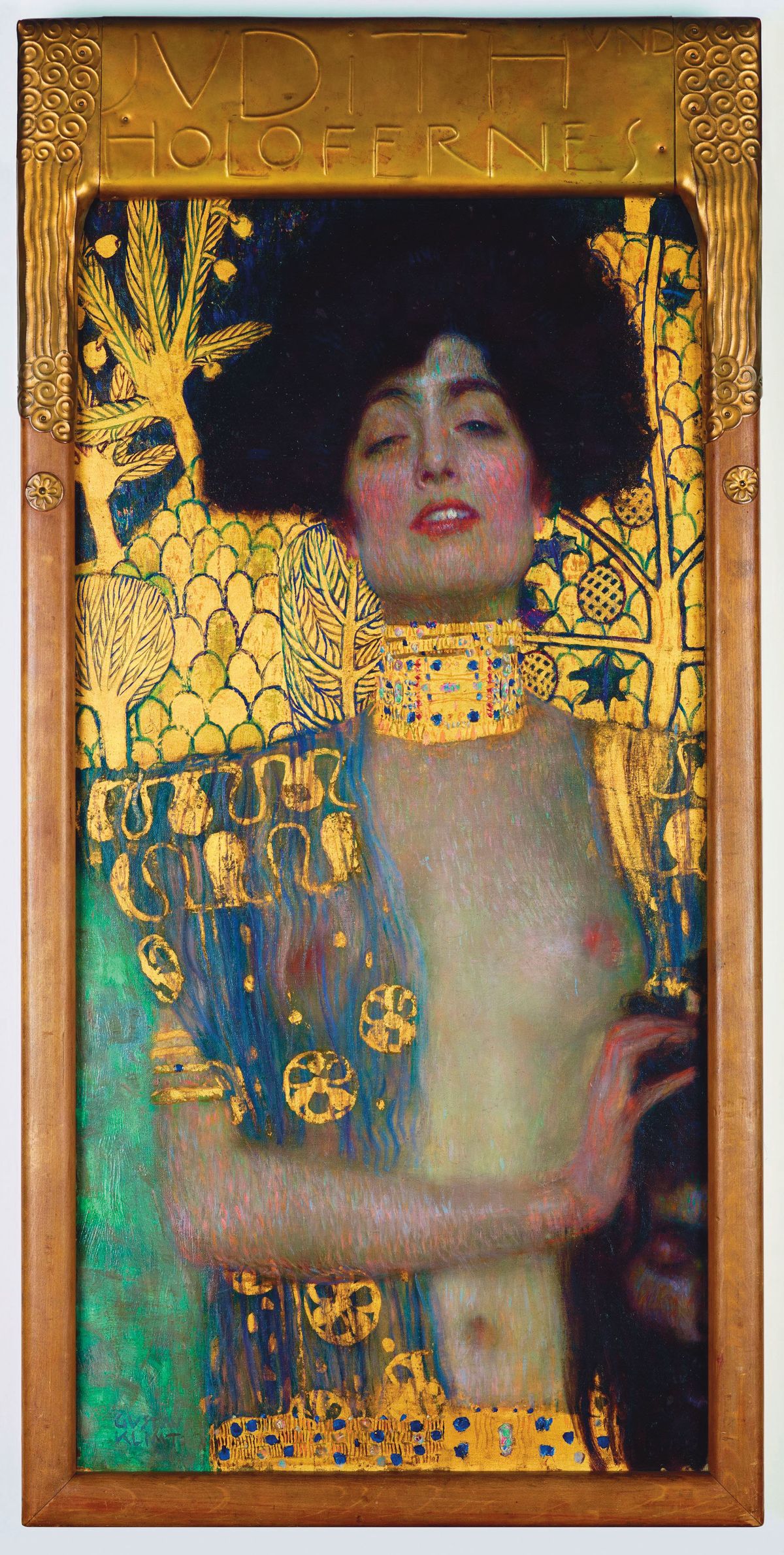

Secessions: Klimt, Stuck, Liebermann reveals how Modernism moved east from Paris in fits and starts. Gustav Klimt was the star of the Viennese iteration, and he is the star attraction in the new Berlin show. Some of his best-known works are making their way to the German capital, including his 1901 breakthrough painting, Judith, in which the biblical heroine, recast as a kind of Circe pinned in place by decorative flourishes, is holding the head of Holofernes.

Max Liebermann's Country House in Hilversum (1901) © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; Nationalgalerie / Jörg P. Anders

Klimt’s fusion of frank sexuality, contemporary fashion and off-kilter composition can still surprise and disturb. He shares top billing here with Berlin’s Max Liebermann, an early and permanent German advocate of Impressionism, and Munich’s Franz von Stuck, who got stuck in Symbolism.

The idea for the show, which is the first of its kind to compare similar trends in the three cities, came from Ralph Gleis, the Alte Nationalgalerie’s director. With 14 Klimt paintings and dozens of prints and drawings—mostly on loan from the Wien Museum, where the show will travel next year—Secessions tries to “put Klimt in a broader context”, Gleis says, adding that it “was a challenge” to convince lenders in Europe and the US to participate in a show that was so eclectic.

Maria Slavona’s Houses in Montmartre (1898); the German Impressionist artist emerged around the same time as Gustav Klimt Photo: Jörg P. Anders; © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie

Liebermann’s Dutch-themed landscape, Country House in Hilversum (1901), and Houses in Montmartre (1898), by another German Impressionist, Maria Slavona, are roughly contemporary with Judith. But, compared with Klimt, the two figures might seem to be mid-to-late 19th-century painters next to a 20th-century pioneer. What they all had in common at the time, stresses Gleis, was the novelty of their approach in Central Europe itself. “The engine of all the secessions,” Gleis says, “was that art should be new.”

Secessions, like wars, can beget more secessions, and the show will end with a glimpse of what the future would hold. In the final section, the Expressionist Max Pechstein’s Poster for the 1st Exhibition of the New Secession, held in Berlin in 1910, in defiance of the 1899 break, shows the influence of primitive art, and even darker urges than Judith’s. And a poster for a similar 1914 show in Munich, by the German sculptor Edwin Scharff, reveals the influence of France’s Aristide Maillol, whose classicism went on to become the dominant presence in the anti-Modernist “return to order” of entre-deux-guerres Paris—and, with much harder edges, would not be out of place in the Third Reich.

• Secessions: Klimt, Stuck, Liebermann, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 23 June-22 October; Wien Museum, Vienna, 22 May-13 October 2024