Hannah Gadsby pulls no punches when it comes to Pablo Picasso. The Australian comedian’s 2018 Netflix comedy special Nanette weaves in a blistering critique of Picasso’s relationship with his teenage muse Marie-Thérèse Walter, 17 years old to his 45 when they first met. “I hate him, but you’re not allowed to,” Gadsby deadpans, because of “Cubism”. The womanising titan of Modern art is “sold to us as this passionate, virile, tormented genius” rather than, by Gadsby’s definition, a misogynist.

After summing up the history of Western art—Picasso included—as “men painting women like they’re flesh vases for their dick flowers”, Gadsby quips: “I think I’ve ruined any chance of getting a job in a gallery now.” Not quite. Five years on from Nanette, the comedian shares title billing with Picasso for an exhibition that the Brooklyn Museum promises will address “the artist’s complicated legacy through a critical, contemporary and feminist lens”.

It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby is one of a raft of exhibitions taking place this year to mark the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death. The umbrella programme, backed by the French and Spanish governments, is called Picasso Celebration 1973-2023. A self-confessed Picasso hater may seem an unlikely guest curator for Brooklyn’s contribution to the celebrations. But Gadsby’s co-curators at the museum, Catherine Morris and Lisa Small, describe the comedian as the “perfect partner” for a show that will foreground “one of the most important conversations happening today in relationship to Picasso”—feminist critique.

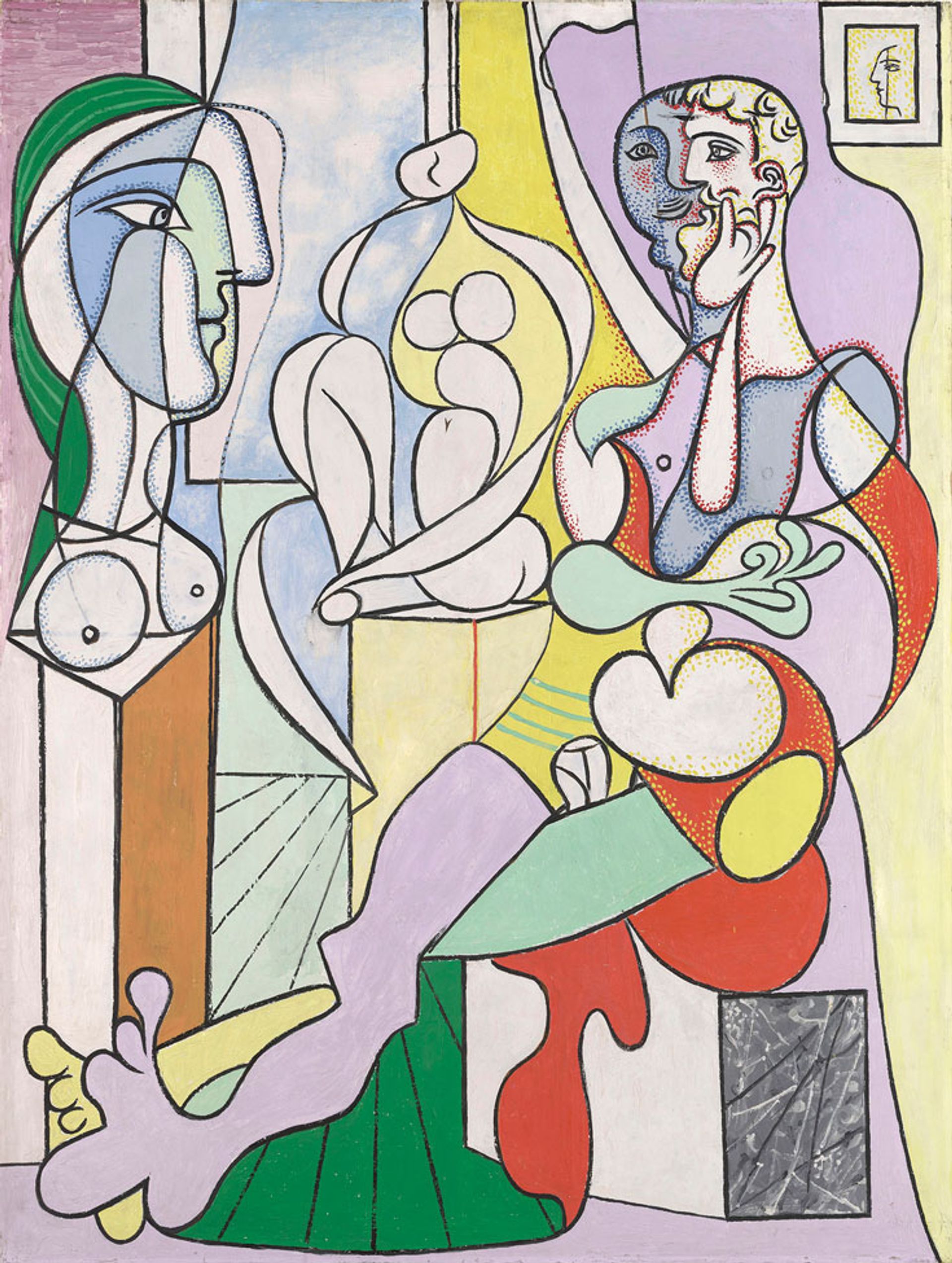

Picasso's The Sculptor, December (1931) Musée national Picasso, Paris; © 2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso, ARS, NY; Photo: Adrien Didierjean, © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

“We were fascinated by Hannah’s engagement with art history,” Morris says, and Gadsby’s take on Picasso as a case study in “systemic cultural damage through misogyny”. Nanette drew direct parallels between Picasso and the latter-day men facing #MeToo reckonings: Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, Roman Polanski. But the curators push back at any notion that the artist is being “cancelled” in this exhibition. Rather, they say, it seeks to grapple with the thorny moral debate catalysed by #MeToo, of what to do with “good” art made by “bad” people, and with the art-world patriarchy exemplified by Picasso. “We’re thinking about making a space for these conversations to happen, to dig into that complexity and not arrive at a prescriptive [message],” Small says.

Gadsby played a key role in developing themes for Brooklyn’s pairings of works by Picasso with pieces from the museum’s own leading collection of feminist art, much of it made since the artist’s death in 1973. Alongside Picasso’s depictions of the recumbent female nude, the studio as “a sexually charged space” and the myth of the minotaur—the artist’s half-man, half-beast alter ego—will hang works that assert women’s bodily and creative agency.

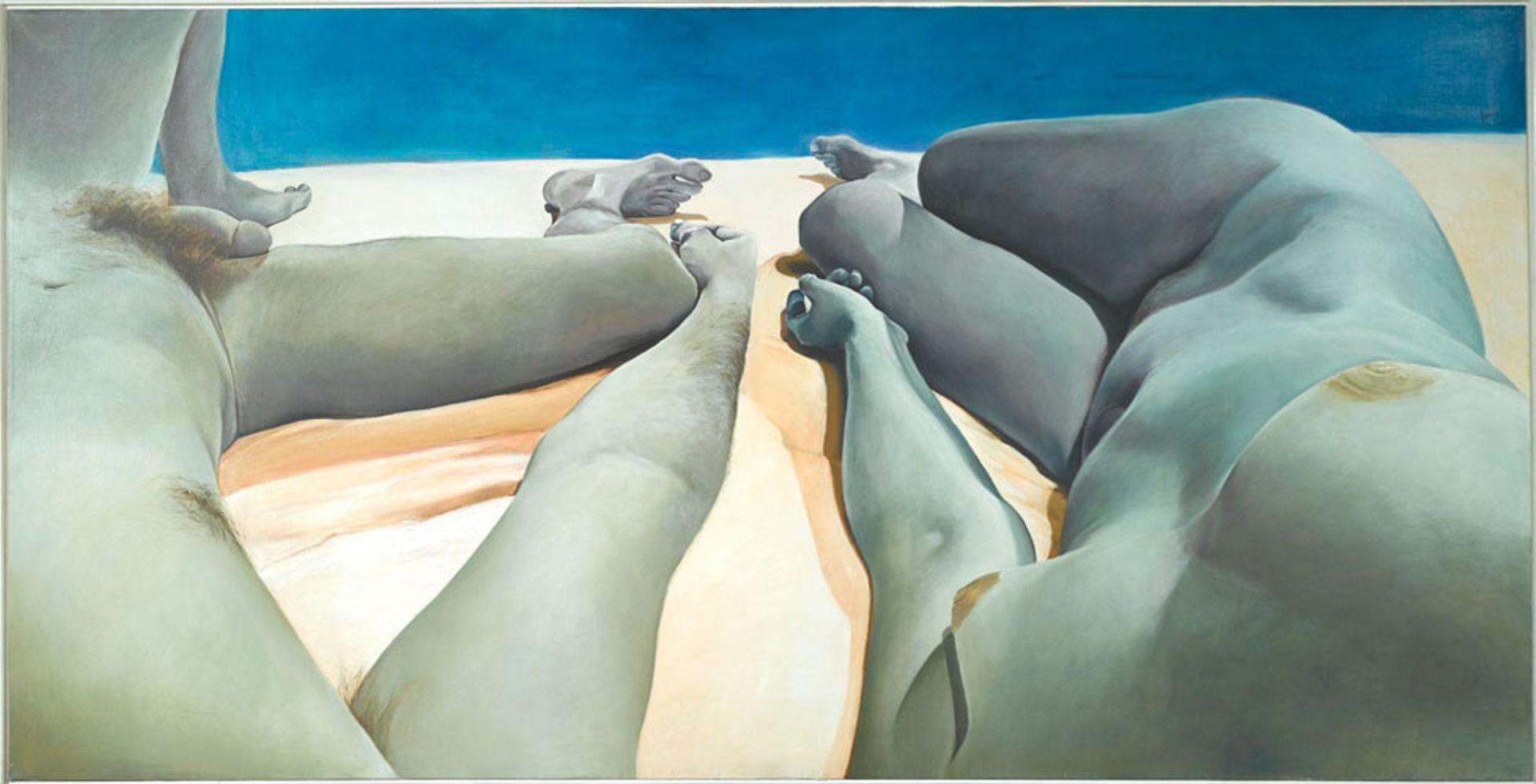

Joan Semmel’s Intimacy Autonomy (1974)

They include Joan Semmel’s “tremendous” double nude Intimacy Autonomy (1974), painted from the perspective of the artist looking down at herself and her partner’s body in bed; Judy Chicago’s illustration of the female-centred erotica of Anais Nin; and Betty Tompkins’s montage of a #MeToo apology statement over Artemisia Gentileschi’s image of Biblical lechery, Susanna and the Elders. “Even if they’re not directly engaging one to one with Picasso,” Small says, these feminist artists were responding to “what his work represents within that larger institutional system of looking at women’s bodies in art”.

The exhibition sets out to deconstruct the “Picasso machine” but also to “reframe the priorities”, Morris says. Picasso’s pictorial obsession with his female muses, and the recurring motif of the artist and model, fuelled a vast body of work in which sexuality was profoundly connected to the power of creativity. The final section of the show will be “devoted to women artists actively engaged in thinking about themselves as both maker and subject”, with no Picassos in sight, shifting the terms of creativity from male mastery over to the next generation.

• It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 2 June-24 September