On 2 June Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum celebrates its 50th birthday, marking its opening in 1973. With a magnificent collection donated by the grandson of Vincent’s brother Theo, it is the world’s greatest museum devoted to a single artist.

Emilie Gordenker, director of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

For this week’s post, I interviewed Emilie Gordenker, who took over as director in February 2020. A specialist in 17th-century Dutch art, she came from the Mauritshuis in The Hague, where she had been director since 2008.

The month after Gordenker’s arrival the museum had to suddenly close because of Covid-19, thrusting the museum into what she describes as “the biggest crisis” in its 50 years. On the eve of the anniversary celebrations, she speaks candidly about the achievements and challenges.

Martin Bailey: Coming to the museum, you must have thought a lot about why Van Gogh is quite so popular with visitors from all around the world. What makes him quite so special?

Emilie Gordenker: We know so much about Van Gogh’s personal life story, through his letters. Most visual artists are not “bilingual”: their primary language is visual and you are lucky if they can also express themselves in words, let alone write in the way that he did. Van Gogh’s paintings are colourful, his subject matter is appealing, it is varied, he is very direct. His life was one of working against the odds: the difficulties that he surmounted represents a fascinating story, one offering solace and hope. There is a freshness and immediacy to his work. Every generation seems to rediscover him.

People are equally interested in Van Gogh’s story and his art. How as a museum do you deal with the story—and particularly his problems?

Until a few years ago we in the museum did not talk much about Van Gogh’s mental state. There was then a very good research project that resulted in an exhibition in 2016, On the Verge of Insanity. Now, at this time, a lot of young people are struggling with mental health issues and are more open about talking about them. Van Gogh offers us—through his writing, his work, his life story—a way of talking about our own situations.

Catalogue of On the Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and his Illness, Van Gogh Museum, 2016

We are at an extraordinarily polarised moment, whether in politics or in our society. Museums are places where people generally trust us. We are a place where things can get discussed, using the example of Van Gogh. It is a way of engaging with people.

What do visitors like and dislike about your museum?

We regularly monitor visitor reactions and always score very well. But if there is a critical note, it is about crowds. People are much more easily disturbed by crowds, post-Covid.

Visitors at the Van Gogh Museum Credit: The Art Newspaper

How are you dealing with crowding?

Popularity is a nice problem to have, but a thorny one. When I arrived we sat down with the staff and board to write a new strategy. Covid pushed us to think really hard about these issues. My predecessors did a marvellous job during a growth period: then it was all about more. But that couldn’t keep going on forever.

We have more visitors per square metre than any other major museum in the world. We have a very good location, a big name and a great collection, but a relatively small building.

When you put all these things together there is more demand than we can provide for. There are very few silver linings to Covid, but timed ticketing is one of them. Visitors have got used to that idea - and we are going to keep it.

The message is not that we want to keep people out. On the contrary, we want people to come, but we want them to have a pleasant visit.

What does this mean in terms of numbers?

During Covid I was confronted with the museum’s biggest crisis in our nearly 50-year history. We receive relatively little subsidy from the government and a large part of our income comes from ticket sales. When half of your income drops out, you think very hard about your financial model. It was an opportunity to rethink that.

We started from scratch. We began by thinking on a cost basis: to carry out our programme, how much do we need to do that? Then the next question is, what is the minimum number of visitors we need to achieve our goal?

This is a different way of thinking. In the past, “more was better”: the more money you got, the more you did. Instead we said, what is really important to do? Which visitors are we not reaching and why? And then, how much money do we need to do it?

We worked out that we will be financially viable with a quarter fewer visitors than we got pre-Covid. In 2019 we had more than 2.1m visitors, but we have now decided on 1.6m a year. Last year, with Covid, we had 1.3m, but this year it will be 1.6m or possibly more, but we do not have to scale up excessively.

The original 1973 Van Gogh Museum building (left) and 1999 exhibition wing and 2015 visitor entrance (right) in Museumplein Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (photograph Jan Kees Steenman)

Couldn't you expand your building, allowing for more visitors?

It is possible, but it would probably be underground. This is something we want to start exploring later this year, but it would take a long time to complete.

How do you arrange your exhibition programme?

This was one of the things that I had to decide on very quickly, since the scheduled programme had to be thrown overboard because of Covid. It was an opportunity to think what do we want to do, going forward. In what period of the year do you want which type of exhibition?

We decided that the autumn, when we have fewer tourists, should be a time for focussing on our Dutch visitors. The perception of our museum had become an issue in the Netherlands, where we were seen as for tourists. It was time to rethink the messaging, so our Dutch visitors would rediscover us. I want them to fall in love with us again. That informed my thinking about exhibitions. In the autumn we will plan solid, well-researched shows with loans.

Spring will be more of an exhibition playground. It will be a time to think more broadly - maybe a project with artists of our own time, perhaps a thematic show, possibly something outside one’s usual comfort zone or even a very scholarly show with not so many visitors.

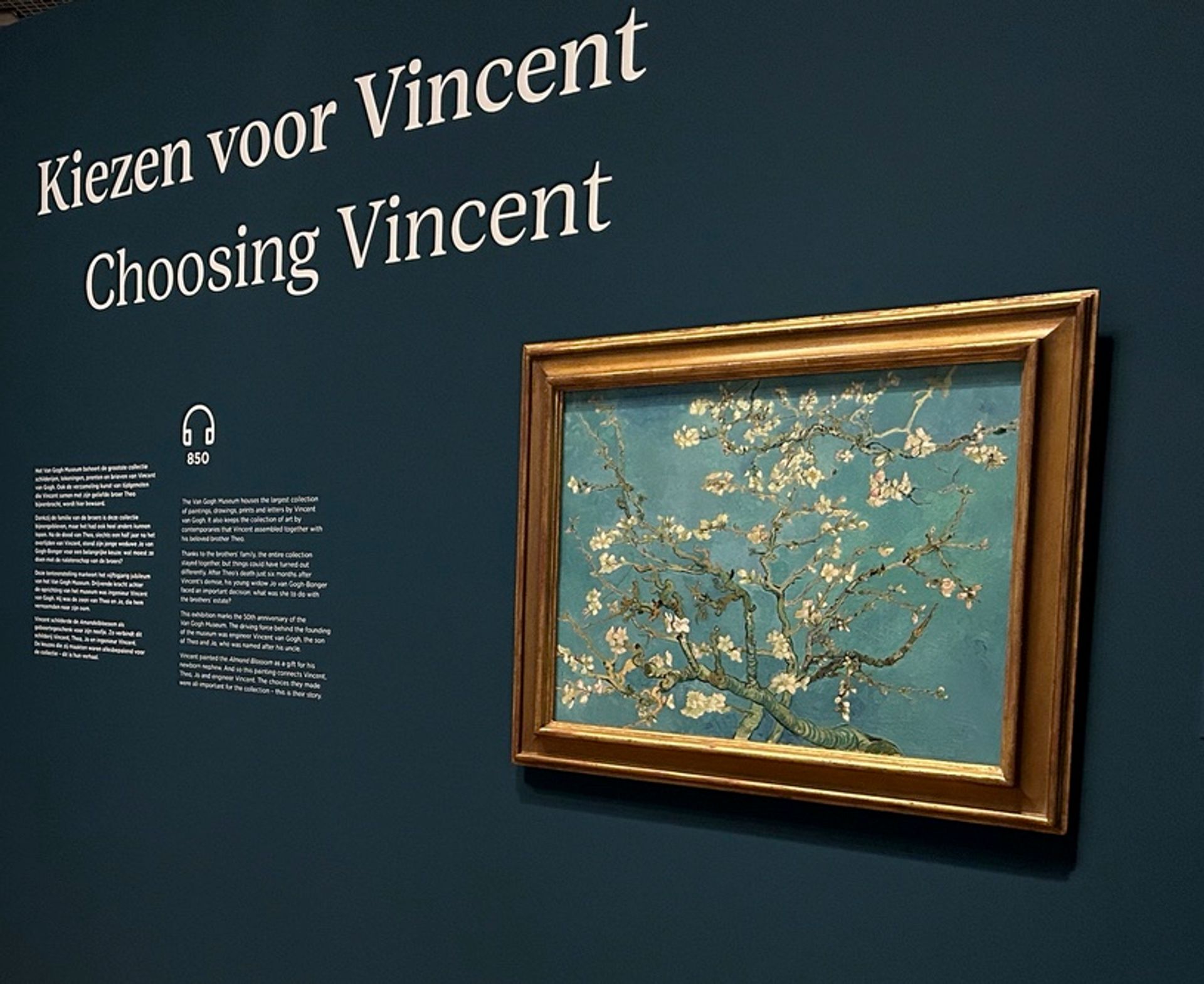

In summer we will bring back the exhibition that we had earlier this year about the Van Gogh family, Choosing Vincent. It’s a great story for first-time visitors. We will present the same show next year, with some modifications, and in the following few summers to come.

The entrance to this year’s presentation of Choosing Vincent Credit: The Art Newspaper

So there will be fewer loan shows. Is this to save money?

That was a consideration, but not the only one. It was mostly about establishing a rhythm. But when you see the rising costs of major loan shows, particularly for transport and insurance, you really do have to think how much you want to spend. Of course we are going to continue with loan shows, since that is what we do well.

How are you going to celebrate the museum’s 50th anniversary?

With a very big party in Museumplein (the large square beside the museum). It will be open to everyone in the afternoon of 2 June.

In the Netherlands, we have a custom that on your birthday you give something back to your friends, it’s called a traktatie (treat). What it is, will be a surprise.

Now for the most difficult question: What will the museum be like in 50 years from now?

No one has a crystal ball. But Van Gogh has had a resonance for every generation. I fully expect that to continue, but exactly how I cannot tell you.

Will people still be going to museums?

I am absolutely certain of that. We have gone very quickly from a culture that is word-based to one that is visual. That has really assisted us as a museum: people are more comfortable about looking at things. So the proliferation of images has helped us make what we have clearer.

The digital is here to stay, it offers us a lot, but it does not replace the actual experience of seeing a work of art. People very much want to see an object. It is always different seeing an artwork in a physical way, a painting on a wall.