Any Matthew Barney exhibition brings out the curious. That has been the case since 1991, when long queues formed outside Barbara Gladstone’s gallery for the opening of his first exhibition in New York.

And so it was again last month, when a burbling horde of invited cognoscenti trekked to Barney’s sculpture studio in Long Island City for the première of his latest work, Secondary. The multi-channel video installation picks apart the spectacle of violence now overtaking America as it plays out in professional football; it’s also a dance.

"I like how much it’s about new work," the artist remarked as cocktails were being served outside, under a setting sun. The studio, I should add, sits opposite the United Nations headquarters on an East River pier and has a magnificent view of Manhattan. This is where Barney made Secondary, as well as scenes for the epic River of Fundament (2007-14) and the recent Redoubt (2018). Because he’s moving to an inland studio nearby, the current exhibition will be the studio’s last hurrah, open to the public until 25 June.

Installation view, Matthew Barney's Secondary, New York, 2023.

Photo: Dario Lasagni © Matthew Barney. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery

At the opening, an air of nostalgia wafted through the warehouse-sized space with a revivifying sense of community. More than one of the artists, museum directors and curators present compared it to a class reunion. “So much has happened here,” said the photographer Ari Marcopoulos, who helped Barney bail out the studio after it was flooded by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. “I’m trying to unwind all the memories,” added a winsome Aimee Mullins, the para-athlete and actress whose roles in Barney’s Cremaster Cycle (1994-2002) and River of Fundament each packed a lasting punch. “This is where I was nearly raped by a live bull,” she recalled, speaking of her first collaboration with the artist and detailing the tortures she underwent during an open rehearsal for Barney’s contribution to the exhibition-cum-performance Il Tempo del Postino at the 2007 Manchester International Festival. Clearly, it didn’t dampen her enthusiasm for the work.

While the sculptures that come of Secondary will be new, the show is replete with references to previous works by Barney. Here, they are elegiac, understated, less surreal than in the past, and given an exquisite new clarity by utilising a new movement vocabulary and new collaborators to share the action.

On the five screens around the arena of the columned space, audience members swivelled heads to watch actors shape signature materials like molten lead, aluminium, and resin to make objects in real time, just as performers in Fundament did. And they’re pushing themselves to their physical limits.

Viewers watched the action on a three-sided jumbotron hanging at the centre of the space, near the ceiling, while lounging or standing on a vast carpet printed with the “field emblem” that Barney introduced in Cremaster I, which unfolds on a football field. Secondary returns to the same tragic incident that inspired it: a 1978 game between the Oakland Raiders and the New England Patriots that left one player, Darryl Stingley, paralysed for life. His attacker, the Raiders’ defensive back Jack Tatum, walked away without apology. Barney watched that incident repeatedly on television as a teen training to be a high-school quarterback and its memory has never left him. Though the ensuing uproar led to better protections for the athletes’ bodies, they didn’t go far enough: the same thing happened to a college football player only last year.

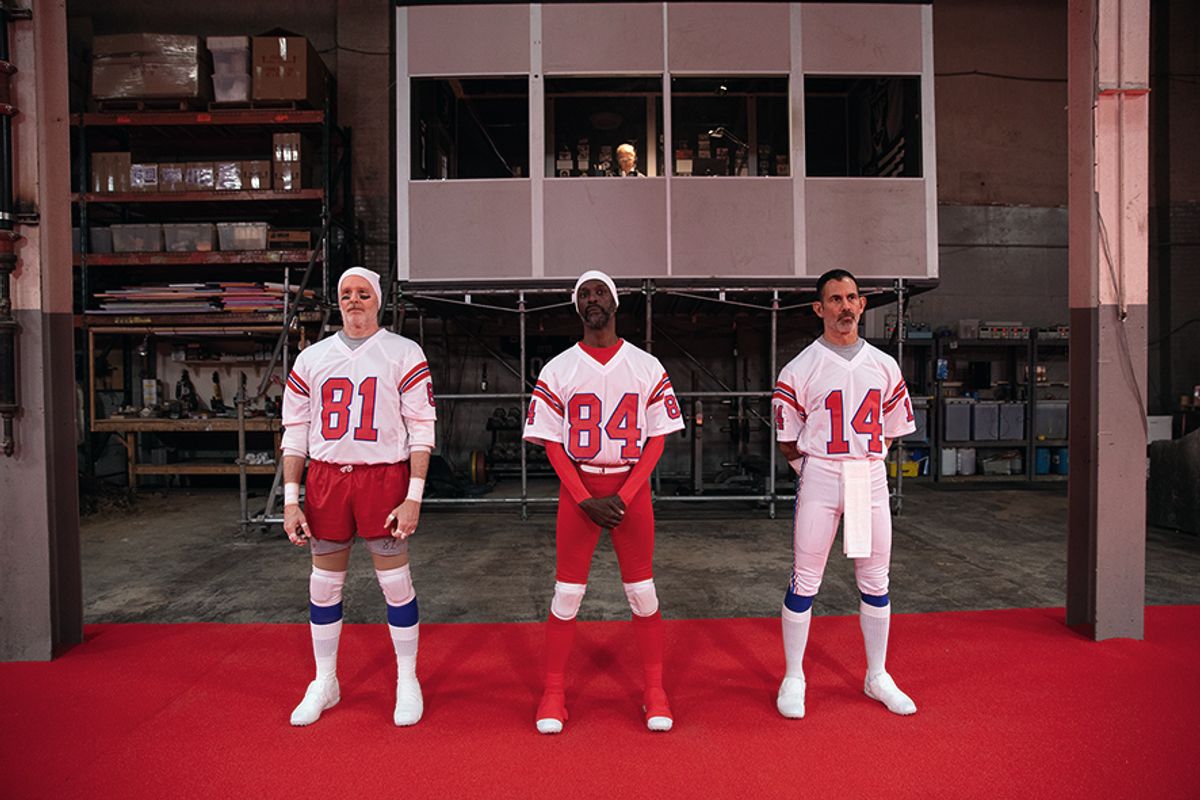

Raiders team from left to right: Shamar Watt (Lester Hayes), Raphael Xavier (Jack Tatum), Matthew Barney (Ken Stabler). Matthew Barney's Secondary (2023)

© Matthew Barney. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Unlike his earlier videos, Secondary adds a pointed commentary to the horror of the subject. Barney appears in an ensemble of performers who developed the piece with him during improvisational workshops led by the choreographer David Thomson, who plays Stingley, and the composer Jonathan Bepler, Barney’s longtime collaborator. “There’s no music,” Bepler told me, “but plenty of sound.” It includes our national anthem—a patriotic ritual that has never made sense to me as a prelude to sporting events. Here it is rendered unrecognisable by the piercing vocalisations of Jacquelyn Deshchidn, a Native American soprano who is, as she wrote in the oversize, souvenir programme, "one of the few surviving Chiricahua Apaches that were called for nothing less than full extermination by governing American officials in 1886".

The character of Jack Tatum (played by the break-dancer Raphael Xavier) meets his fate in motion slowed to a crawl, so that we can see every expression of pain in his body in extremis as if it were an inanimate sculpture—a thing of beauty floating through time. And a disconcerting image, to say the least.

Sports are more dangerous than art. That’s a fact. Even if art today could threaten market consensus—it seldom does—it won’t put anyone on life support. What it can do is give the status quo a bruising. In that vein, Secondary is almost a public service functioning at the highest level on all fronts.

“It’s not exactly The Hunger Games,” observed the Museum of Modern Art’s chief curator of performance, Stuart Comer, “but you do get a sense of apocalypse.”

His was not the only spontaneous review. The actor Rupert Friend, who is married to Mullins, took my notebook in his hand to pen his own after just five minutes of the hour-long video—brief as a wink for this commanding artist. “Barney’s show,” Friend wrote, “is something akin to a picnic. There’s the lemonade, the rug, and the ballgame, but you wouldn’t leave your kill unattended. I’ll come again.”

I will too.