It is painfully clear that there is a need for a profound reset in education in the UK. With a general election likely next year, it is time for Keir Starmer’s Labour Party to start talking about the role of creativity in education. Socially, economically and technologically, our world has been transformed over the past five decades: the climate crisis; the rise of China; diversity, equality and inclusion; mass expansion of higher education; the invention of the world-wide-web; automation; smartphones; artificial intelligence (AI). The list goes on.

The skills demanded in the jobs of today are critical thinking, problem-solving, communication skills, emotional intelligence, empathy and self-confidence. The case could not be clearer for the centrality of creativity in education. To adapt the great Labour MP Nye Bevan’s phrase, the pedagogy of turning out pupils who are “desiccated calculating-machines” is over.

Since Prime Minister James Callaghan launched the “Great Education Debate” with his speech in 1976 at Ruskin College, Oxford, Thomas Gradgrind—the school board Superintendent of Coketown in the Charles Dickens novel Hard Times—has been the patron saint of UK education reform: “Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!”

It is a bitter truth of satire that mocking stupidity doesn’t kill it. Despite Dickens’s brutal depiction of the emptiness of purely instrumental education, for nearly 50 years it has driven all before it—“Out with the fun, in with curriculum reform.”

It is time for Labour to drive a new approach. What demands change is first that we have got to the end of the benefits from the neoliberal changes introduced into education—the devolution of power to headteachers, the creation of academies, and the regime that means we have the most tested kids in the world.

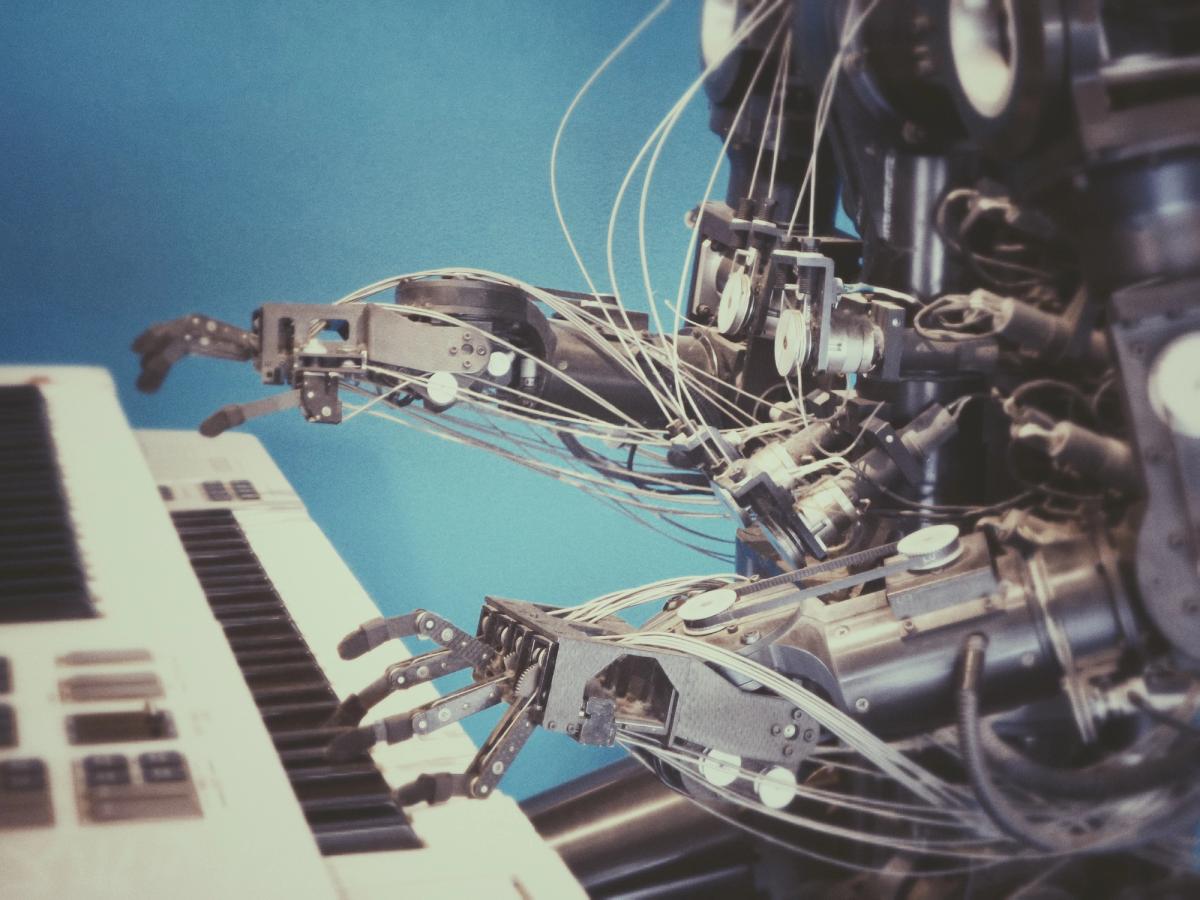

An AI turning point

But secondly, and much more importantly, we have reached a turning point in our intellectual history as a species with the advances in artificial intelligence (AI). In recent months many have become aware of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, which its website describes as: “[a model] which interacts in a conversational way. The dialogue format makes it possible for ChatGPT to answer follow-up questions, admit its mistakes, challenge incorrect premises, and reject inappropriate requests.”

And rapidly parents and pupils alike have been finding that it generates very good essays and exam question answers. The process of improving this AI has created GPT-4, which can, OpenAI claims, beat 90% of humans in the US Bar Exam and 88% in the Law School Admission Test.

This leads to the fundamental questions of not just how we are educating children and young people, but how we are going about it—and to what ends.

Since at least the 1950s, there have been warnings that “the robots are coming”, and that fear has never materialised. Yet, as a panellist at a seminar I hosted recently on the challenges of regulating AI said: “What if it’s different now? Can you name a job that is done today by a human that couldn’t be done by AI in the future?” That question has stayed with me in the weeks since, and I have gone through a list of roles and professions—scoring off tasks, and indeed entire ranks of workers.

What is the distinctive human factor and where is it essential?

In live performance, obviously. Who wants to see 22 AIs rather than a classic football derby, or to listen to a ChatGPT stand-up routine rather than be in a room with a comedian drawing attention, demanding a response and surfing on the energy of the laughter?

It’s in the human interaction in real time, unique and unrepeatable. It’s qualities like empathy, appreciation of nuance and emotional intelligence. As the novelist Iris Murdoch put it in a riposte to C.P. Snow in her 1972 Blashfield Address to the American Academy of Arts and Letters: “There are not two cultures. There is only one culture and words are its basis; words are where we live as human beings and as moral and spiritual agents.” Far from Gradgrind! Of course, those of us who have been transfixed by Merce Cunningham’s dance company, inspired by Louise Bourgeois’s sculptures or mesmerised by a Loraine James set know that physical, visual and musical art impacts powerfully and humanly too.

It is moral and spiritual agency that should be nurtured through education—time for boldness from the Labour Party. Nothing could be more future-facing or progressive than placing creativity at the heart of education for this new century, this brave new world.

• John McTernan is a Labour strategist and former political secretary to Prime Minister Tony Blair (2005-07)