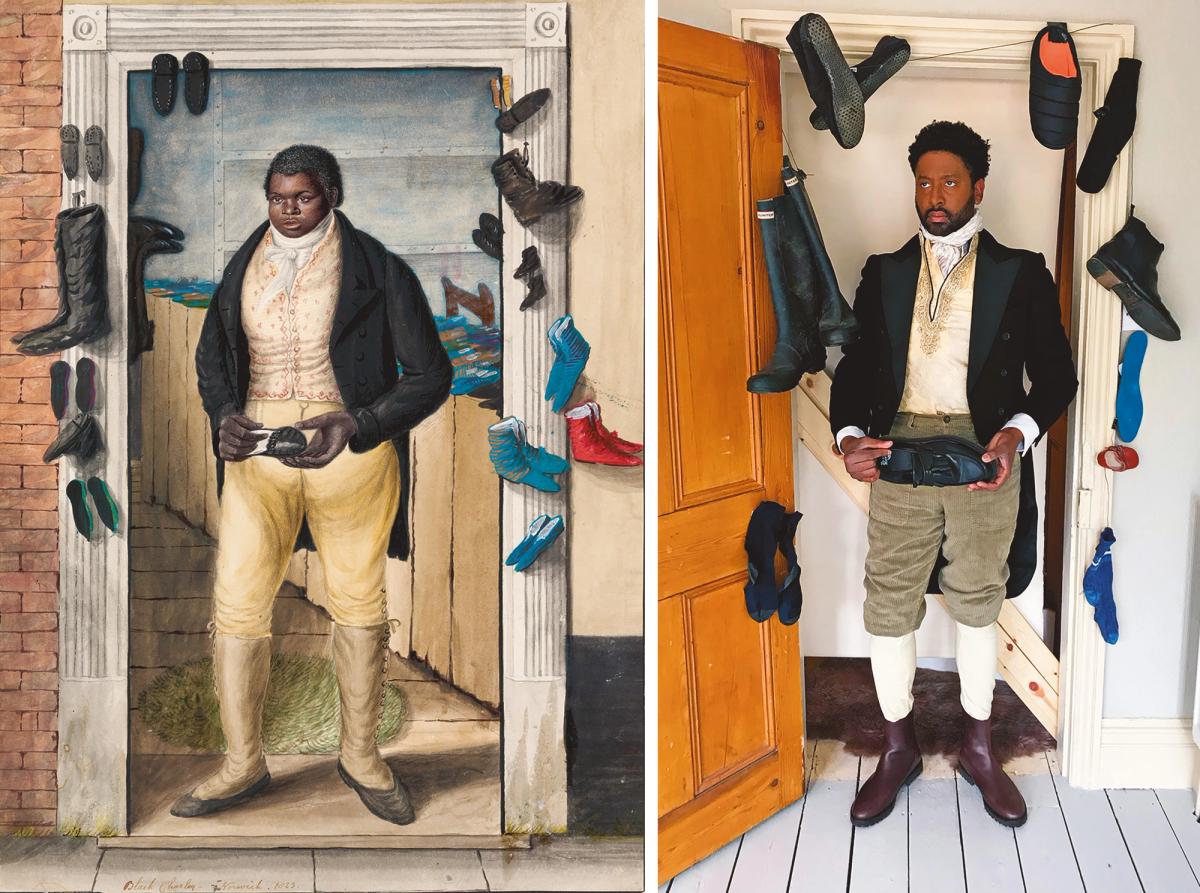

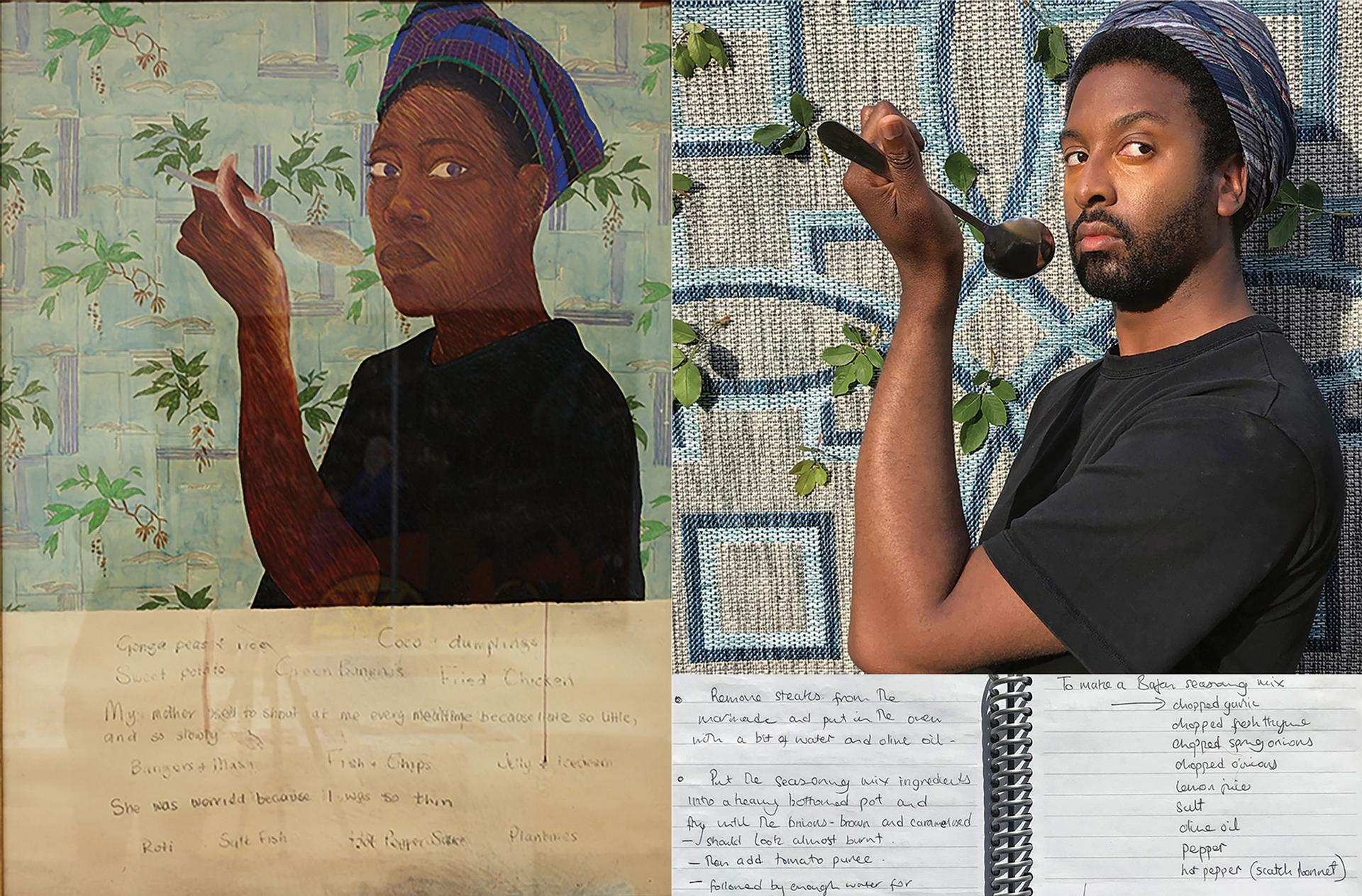

Prompted by the Getty Museum Challenge—which involved using household items to restage famous paintings on social media during Covid-19 lockdowns—the renowned UK opera singer Peter Brathwaite began researching more than 100 works of art featuring Black sitters. The works, presented in Rediscovering Black Portraiture where they are re-created by Brathwaite, span antiquity to the present, including his own reconfigurations of key pieces such as The Adoration of the Magi (1480-90) by Georges Trubert, Black Charley, Norwich (around 1823) by John Dempsey and Rice n Peas (1982) by Sonia Boyce.

“Scrolling through social media, my feed was awash with people who had taken up the challenge, re-creating their favourite artworks using everyday items found at home. The submissions exposed the depressing truth that most of the so-called great artworks we choose to platform and celebrate do not tell the stories of people of colour—the global majority,” Brathwaite writes in the introduction.

The publication provides insights into the props and processes behind the works, conveying the humour and joy of using what you have to hand at home, Brathwaite says. Discarded birthday bunting was, for instance, “a gift in the restaging of the Virgin of Guadalupe (anonymous, 1745) and does a lot of the legwork for me in that re-creation”.

The restaging of The Paston Treasure by an unknown Dutch artist (1670s) required the most preparation and set building, Brathwaite reveals. “I spent hours running around the house and scouring the attic to source the items for my interpretation of that iconic banquet scene. There’s a really satisfying process from doing the research, to finding the props, to building the scenes, to stepping into what I see as a performance, and then the liminal post-performance bit of removing the costume and packing everything away again! I’m drawing on my performance background throughout.”

Before postgraduate opera training at the Royal College of Music in London, Brathwaite graduated in fine art and philosophy from Newcastle University. Studying the work of the US artist Mike Kelley was a key turning point, he says. “His oeuvre of found objects, textile banners, drawings, assemblage, performance and video deeply influenced the work I produced back then. I definitely feel his influence in the work I make now; my portraiture restagings are all about unpicking ritual and tradition.”

But his hugely popular recreation project is not just about dressing up. The book arguably reclaims Black history and art. “I’m reclaiming the narrative on my own terms in the hope that these marginalised Black lives can be made visible or seen anew,” Brathwaite says. “So much of this work is about what it means to build identity in the African and Caribbean diaspora, especially when, in many cases, there are only fragments.”

Sonia Boyce's Rice n Peas (1982) and Brathwaite's recreation © Sonia Boyce / ARS, NY; DACS, London; Courtesy of Simon Lee Gallery; Photo: Denise Swanson. Photo: Sam Baldock © Peter Brathwaite

Indeed, the project and publication helped uncover key aspects of his Barbadian heritage. “It’s enabled me to process much of what I already knew but that was submerged or put aside out of fear of not fitting in.” There are recurring motifs and props that carry weight, like the cou-cou stick, a Barbadian cooking implement, and the heirloom patchwork quilts made by his grandmother.

“These props have enabled me to develop a language that speaks to subdued parts of my own mixed Barbadian-British identity and are useful routes into the subdued histories I’ve encountered throughout the course of this project. They’re signposts. They ask you to look again.”

Brathwaite also discusses how he reimagined two recognisable and important works, Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) and Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of the former US President Barack Obama (2018). “My re-staging of Manet’s Olympia crops the original work to focus solely on Laure, the African or Caribbean woman whose pink dress, white collar and madras headdress—a typical component of dress in Dominica, Saint Lucia and many other Caribbean islands—allude to African-European identity and blending of cultures imbued with symbolic power. In my re-creation I’m clutching the family historical documents that speak to the dark historical bonds that define my own mixed-ness,” he says. “The Obama re-staging was especially interesting because Wiley has already done the work of centring his subject. I could simply wallow in the joy of inhabiting the role, albeit sat on a chair that was precariously perched on a makeshift platform of bricks, and with a backdrop of exfoliating shower puffs.”

Brathwaite’s latest piece, The Young Catechist (1827) by Henry Meyer, was commissioned by the UK’s Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, for his Rediscovering Black Portraiture exhibition (until 3 September).

He notes finally the challenging aspects of the project. “In the beginning, the most difficult aspect of the work was how to recreate certain portraits without perpetuating the racialised trauma many of the original images hold. Each re-staging is an act of confronting painful legacies of enslavement and colonialism, searching for transformative layers of healing and justice. I do this by sharing my own personal story.” The question of Black presence in Western visual culture is meanwhile still a pressing issue. “The work is about the conversations we’re having now. What assumptions do we make? It’s about what we see when we look at one another.”

• Rediscovering Black Portraiture, Peter Brathwaite, Getty Publications, 168pp, £35 (hb)